Edicts of Ashoka

As historian Romila Thapar relates: In his edicts Aśoka defines the main principles of dhamma as non-violence, tolerance of all sects and opinions, obedience to parents, respect to brahmins and other religious teachers and priests, liberality toward friends, humane treatment of servants and generosity towards all.

The identification of Devanampiya with Ashoka was confirmed by an inscription discovered in 1915 by C. Beadon, a British gold-mining engineer, at Maski, a town in Madras Presidency (present day Raichur district, Karnataka).

Another minor rock edict, found at the village Gujarra in Gwalior State (present day Datia district of Madhya Pradesh), also used the name of Ashoka together with his titles: Devanampiya Piyadasi Asokaraja.

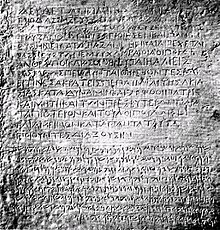

[6] The inscriptions revolve around a few recurring themes: Ashoka's conversion to Buddhism, the description of his efforts to spread dhamma, his moral and religious precepts, and his social and animal welfare program.

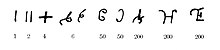

[9] The task was then completed by James Prinsep, an archaeologist, philologist, and official of the East India Company, who was able to identify the rest of the Brahmi characters, with the help of Major Cunningham.

[9][10] In a series of results that he published in March 1838 Prinsep was able to translate the inscriptions on a large number of rock edicts found around India, and to provide, according to Richard Salomon, a "virtually perfect" rendering of the full Brahmi alphabet.

[13][14] The Kharoshthi script, written from right to left, and associated with Aramaic, was also deciphered by James Prinsep in parallel with Christian Lassen, using the bilingual Greek-Kharoshthi coinage of the Indo-Greek and Indo-Scythian kings.

[15][16] "Within the incredibly brief space of three years (1834-37) the mystery of both the Kharoshthi and Brahmi scripts (were unlocked), the effect of which was instantly to remove the thick crust of oblivion which for many centuries had concealed the character and the language of the earliest epigraphs".

[21] On the contrary, the Major Rock Edicts and Major Pillar Edicts are essentially moral and political in nature: they never mention the Buddha or explicit Buddhist teachings, but are preoccupied with order, proper behavior and non violence under the general concept of "Dharma", and they also focus on the administration of the state and positive relations with foreign countries as far as the Hellenistic Mediterranean of the mid-3rd century BCE.

The Rummindei and Nigali Sagar edicts, inscribed on pillars erected by Ashoka later in his reign (19th and 20th year) display a high level of inscriptional technique with a good regularity in the lettering.

[32] These Edicts were concerned with practical instructions in running the empire such as the design of irrigation systems and descriptions of Ashoka's beliefs in peaceful moral behavior.

[31] Chronologically they follow the fall of Seleucid power in Central Asia and the related rise of the Parthian Empire and the independent Greco-Bactrian Kingdom circa 250 BCE.

[47] The Dharma preached by Ashoka is explained mainly in term of moral precepts, based on the doing of good deeds, respect for others, generosity and purity.

(Major Pillar Edict No.2)[28]Thus the glory of Dhamma will increase throughout the world, and it will be endorsed in the form of mercy, charity, truthfulness, purity, gentleness, and virtue.

Ashoka showed great concern for fairness in the exercise of justice, caution and tolerance in the application of sentences, and regularly pardoned prisoners.

When Ashoka embraced Buddhism in the latter part of his reign, he brought about significant changes in his style of governance, which included providing protection to fauna, and even relinquished the imperial hunt.

(Major Rock Edict No.4, Shahbazgarhi)[59]Ashoka advocated restraint in the number that had to be killed for consumption, protected some of them, and in general condemned violent acts against animals, such as castration.

However, the edicts of Ashoka reflect more the desire of rulers than actual events; the mention of a 100 'panas' (coins) fine for poaching deer in imperial hunting preserves shows that rule-breakers did exist.

(Minor Rock Edict No.3)[28]These sermons on Dhamma, Sirs - the Excellence of the Discipline, the Lineage of the Noble One, the Future Fears, the Verses of, the Sage, the Sutra of Silence, the Question, of Upatissa, and the Admonition spoken by the Lord Buddha to Rahula on the subject of false speech - these sermons on the Dhamma, Sirs, I desire that many monks and nuns should hear frequently and meditate upon, and likewise laymen and laywomen.

They are occupied with servants and masters, with Brahmanas and Ibhiyas, with the destitute; (and) with the aged, for the welfare and happiness of those who are devoted to morality, (and) in releasing (them) from the fetters (of worldly life).

(He) made the village of Lumbini free of taxes, and paying (only) an eighth share (of the produce).𑀤𑁂𑀯𑀸𑀦𑀁𑀧𑀺𑀬𑁂𑀦 𑀧𑀺𑀬𑀤𑀲𑀺𑀦 𑀮𑀸𑀚𑀺𑀦𑀯𑀻𑀲𑀢𑀺𑀯𑀲𑀸𑀪𑀺𑀲𑀺𑀢𑁂𑀦 Devānaṃpiyena Piyadasina lājina vīsati-vasābhisitena 𑀅𑀢𑀦𑀆𑀕𑀸𑀘 𑀫𑀳𑀻𑀬𑀺𑀢𑁂 𑀳𑀺𑀤𑀩𑀼𑀥𑁂𑀚𑀸𑀢 𑀲𑀓𑁆𑀬𑀫𑀼𑀦𑀺𑀢𑀺 atana āgācha mahīyite hida Budhe jāte Sakyamuni ti 𑀲𑀺𑀮𑀸𑀯𑀺𑀕𑀥𑀪𑀺𑀘𑀸𑀓𑀸𑀳𑀸𑀧𑀺𑀢 𑀲𑀺𑀮𑀸𑀣𑀪𑁂𑀘 𑀉𑀲𑀧𑀸𑀧𑀺𑀢𑁂 silā vigaḍabhī chā kālāpita silā-thabhe cha usapāpite 𑀳𑀺𑀤𑀪𑀕𑀯𑀁𑀚𑀸𑀢𑀢𑀺 𑀮𑀼𑀁𑀫𑀺𑀦𑀺𑀕𑀸𑀫𑁂 𑀉𑀩𑀮𑀺𑀓𑁂𑀓𑀝𑁂 hida Bhagavaṃ jāte ti Luṃmini-gāme ubalike kaṭe 𑀅𑀞𑀪𑀸𑀕𑀺𑀬𑁂𑀘 aṭha-bhāgiye cha In order to propagate welfare, Ashoka explains that he sent emissaries and medicinal plants to the Hellenistic kings as far as the Mediterranean, and to people throughout India, claiming that Dharma had been achieved in all their territories as well.

[97][98] Colonial era scholars such as Rhys Davids have attributed Ashoka's claims of "Dharmic conquest" to mere vanity, and expressed disbelief that Greeks could have been in any way influenced by Indian thought.

[107][108][109] According to semitologist André Dupont-Sommer, speaking about the consequences of Ashoka's proselytism: "It is India which would be, according to us, at the beginning of this vast monastic current which shone with a strong brightness during about three centuries in Judaism itself".

Greek communities also lived in the northwest of the Mauryan Empire, currently in Pakistan, notably ancient Gandhara, and in the region of Gedrosia, nowadays in Southern Afghanistan, following the conquest and the colonization efforts of Alexander the Great around 323 BCE.

The Kambojas are a people of Central Asian origin who had settled first in Arachosia and Drangiana (today's southern Afghanistan), and in some of the other areas in the northwestern Indian subcontinent in Sindh, Gujarat and Sauvira.

[118] It has also been suggested that inscriptions bearing the Delphic maxims from the Seven Sages of Greece, inscribed by philosopher Clearchus of Soli in the neighbouring city of Ai-Khanoum circa 300 BCE, may have influenced the writings of Ashoka.

However, the specific edict mentioned by Fa-Hien has not yet been discovered.On the surface of this pillar is an inscription to the following effect: “King Asoka presented the whole of Jambudvipa to the priests of the four quarters, and redeemed it again with money, and tins he did three times.”

On this spot he raised the city of Ni-li, and in the midst of it erected a stone pillar, also about 35 feet in height, on the top of which he placed the figure of a lion, and also engraved an historical record on the pillar giving an account of the successive events connected with Ni-li, with the corresponding year, day, and month.— Chapter XXVII , The travels of Fa Hian (400 A.D.)[134]According to some scholars such as Christopher I. Beckwith, Ashoka, whose name only appears in the Minor Rock Edicts, should be differentiated from the King Piyadasi, or Devanampiya Piyadasi (i.e. "Beloved of the Gods Piyadasi", "Beloved of the Gods" being a fairly widespread title for "King"), who is named as the author of the Major Pillar Edicts and the Major Rock Edicts.

[135] Since he does mention a pilgrimage to Sambhodi (Bodh Gaya, in Major Rock Edict No.8) however, he may have adhered to an "early, pietistic, popular" form of Buddhism.

[135] However, many of Beckwith's methodologies and interpretations concerning early Buddhism, inscriptions, and archaeological sites have been criticized by other scholars, such as Johannes Bronkhorst and Osmund Bopearachchi.

𑀮

La+

𑀺

i; pī=

𑀧

Pa+

𑀻

ii).

and not "Li"

and not "Li"

.

[

112

]

.

[

112

]