Buddhism and Western philosophy

In antiquity, the Greek philosopher Pyrrho traveled with Alexander the Great's army on its conquest of India (327 to 325 BCE) and based his philosophy of Pyrrhonism on what he learned there.

After WWII spread of Buddhism to the West scholarly interest arose in a comparative, cross-cultural approach between Eastern and Western philosophy.

This is similar to the Buddha's refusal to answer certain metaphysical questions which he saw as non-conductive to the path of Buddhist practice and Nagarjuna's "relinquishing of all views (drsti)".

In Pyrrhonism: How the Ancient Greeks Reinvented Buddhism, Kuzminski writes: "its origin can plausibly be traced to the contacts between Pyrrho and the sages he encountered in India, where he traveled with Alexander the Great.

The Scottish philosopher David Hume wrote: "When I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure.

[5]This 'Bundle theory' of personal identity is very similar to the Buddhist notion of not-self, which holds that the unitary self is a fiction and that nothing exists but a collection of five aggregates.

[6][7] Similarly, both Hume and Buddhist philosophy hold that it is perfectly acceptable to speak of personal identity in a mundane and conventional way, while believing that there are ultimately no such things.

According to Parfit, apart from a causally connected stream of mental and physical events, there are no "separately existing entities, distinct from our brains and bodies".

[10] Other Western philosophers that have attacked the view of a fixed self include Daniel Dennett (in his paper 'The Self as a Center of Narrative Gravity') and Thomas Metzinger ('The Ego Tunnel').

Some Buddhist philosophical views have been interpreted as having Idealistic tendencies, mainly the cittamatra (mind-only) philosophy of Yogacara Buddhism[11] as outlined in the works of Vasubandhu and Xuanzang.

Buddhologists like Edward Conze have also seen similarities between Kant's antinomies and the unanswerable questions of the Buddha in that "they are both concerned with whether the world is finite or infinite, etc., and in that they are both left undecided.

"[17] Schopenhauer's view that "suffering is the direct and immediate object of life"[18] and that this is driven by a "restless willing and striving" are similar to the Four Noble Truths of the Buddha.

[20] His view that a single world-essence (The Will) comes to manifest itself as a multiplicity of individual things (principium individuationis) has been compared to the Buddhist trikaya doctrine as developed in Yogacara Buddhism.

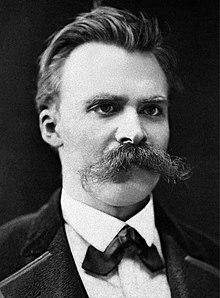

"[25] Because of this writes Elman, Nietzsche misinterprets Buddhism as promoting "nothingness" and nihilism, all of which the Buddha and other Buddhist thinkers such as Nagarjuna repudiated, in favor of a subtler understanding of Shunyata.

[26] Ultimately both world views have as their ideal what Panaïoti calls "great health perfectionism" which seeks to remove unhealthy tendencies from human beings and reach an exceptional state of self-development.

[27] Morrison also sees an affinity between the Buddhist concept of tanha, or craving and Nietzsche's view of the will to power as well as in their understandings of personality as a flux of different psycho-physical forces.

[25] David Loy also quotes Nietzsche's views on the subject as "something added and invented and projected behind what there is" (Will to Power 481) and on substance ("The properties of a thing are effects on other 'things' ... there is no 'thing-in-itself.'"

Loy however sees Nietzsche as failing to understand that his promotion of heroic aristocratic values and affirmation of will to power is just as much of a reaction to the 'sense of lack' which arises from the impermanence of the subject as what he calls slave morality.

[33] Christian Coseru argues in his monograph "Perceiving reality" that Buddhist philosophers such as Dharmakirti, Śāntarakṣita and Kamalaśīla "share a common ground with phenomenologists in the tradition of Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty."

Modern Buddhist thinkers who have been influenced by Western Phenomenology and Existentialism include Ñāṇavīra Thera, Nanamoli Bhikkhu, R. G. de S. Wettimuny, Samanera Bodhesako and Ninoslav Ñāṇamoli.

Edmund Husserl, the founder of Phenomenology, wrote that "I could not tear myself away" while reading the Buddhist Sutta Pitaka in the German translation of Karl Eugen Neumann.

"[37] After reading the Buddhist texts, Husserl wrote a short essay entitled 'On the discourses of Gautama Buddha' (Über die Reden Gotomo Buddhos) which states: Complete linguistic analysis of the Buddhist canonical writings provides us with a perfect opportunity of becoming acquainted with this means of seeing the world which is completely opposite of our European manner of observation, of setting ourselves in its perspective, and of making its dynamic results truly comprehensive through experience and understanding.

That Buddhism - insofar as it speaks to us from pure original sources - is a religio-ethical discipline for spiritual purification and fulfillment of the highest stature - conceived of and dedicated to an inner result of a vigorous and unparalleled, elevated frame of mind, will soon become clear to every reader who devotes themselves to the work.

However Husserl also thought that Buddhism has not developed into a unifying science which can unite all knowledge since it remains a religious-ethical system and hence it is not able to qualify as a full transcendental phenomenology.

[36] According to Aaron Prosser, "The phenomenological investigations of Siddhartha Gautama and Edmund Husserl arrive at the exact same conclusion concerning a fundamental and invariant structure of consciousness.

[44] Jean-Paul Sartre believed that consciousness lacks an essence or any fixed characteristics and that insight into this caused a strong sense of existential angst or nausea.

The unity of body and mind (shēnxīn, 身心) expressed by the Buddhism of Dogen and Zhanran and Merleau-Ponty's view of the corporeity of consciousness seem to be in agreement.

[51] Nishida saw the Absolute nature of reality as Nothingness, a "formless", "groundless ground" which envelops all beings and allows them to undergo change and pass away.

[52][53] Like Buddhism, Whitehead also held that our understanding of the world is usually mistaken because we hold to the 'fallacy of misplaced concreteness' in seeing constantly changing processes as having fixed substances.