Bulla (seal)

[1]: 24 From about the 4th millennium BC onwards, as communications on papyrus and parchment became widespread, bullae evolved into simpler tokens that were attached to the documents with cord, and impressed with a unique sign (i.e., a seal)[1]: 29 to provide the same kind of authoritative identification and for tamper-proofing.

[2] Clay tokens allowed agriculturalists to keep track of animals and food that had been traded, stored, and/or sold.

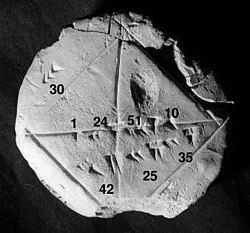

From 2600 BC onwards, the Sumerians wrote multiplication tables, division problems, and geometry on clay tablets.

Denise Schmandt-Besserat of the University of Texas at Austin in the early 1970s is noted for her research and theory of the evolution of bullae into mathematics.

She suggested that the earliest tokens were simple shapes and were comparatively unadorned; they represented basic agricultural commodities such as grain and sheep.

This complexity was reflected in the tokens, which begin to appear in a much greater diversity of shapes with more complicated designs of incisions and holes.

This practice, in place by about 3000 BC, afforded greater ease of use and storage, at a price of a certain loss of security.

[5] As papyrus and parchment gradually replaced clay tablets, bullae became the new encasement for scrolls of this new writing style.

Clay was impressed on the cord to avoid unauthorized reading and the bottom of the document was then wrapped around the initial scroll.

Bullae found in dig sites that appear concave and smooth and unmarked are thus these initial molds of clay placed around the interior scroll.

Designs were inscribed on the clay seals to mark ownership, identify witnesses or partners in commerce, or control of government officials.

[8] In many cases, fingerprints of the person who made the impression remain visible near the border of the seal in the clay.

On the other hand, those bullae used for royals and important functionaries generally bear the owner’s bust accompanied by an inscription giving the name and title.

[11] French-American archaeologist Denise Schmandt-Besserat focused much of her career on the discovery of over 8,000 ancient tokens found in the Middle East.

Within a year of studying these unknown clay marbles, Schmandt-Besserat determined that they were tokens that were supposed to be grouped together and that they thus formed some sort of counting system.

The transition between hunting and gathering to settling and agriculture took place in the period 8,000 to 7,500 BC in the Ancient Near East and involved a need to store grains and other goods.

1 + 24/60 + 51/60 2 + 10/60 3 = 1.41421296... The tablet also gives an example where one side of the square is 30, and the resulting diagonal is 42 25 35 or 42.4263888...