Square root of 2

Technically, it should be called the principal square root of 2, to distinguish it from the negative number with the same property.

Sequence A002193 in the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences consists of the digits in the decimal expansion of the square root of 2, here truncated to 65 decimal places:[2] The Babylonian clay tablet YBC 7289 (c. 1800–1600 BC) gives an approximation of

, representing a margin of error of only –0.000042%: Another early approximation is given in ancient Indian mathematical texts, the Sulbasutras (c. 800–200 BC), as follows: Increase the length [of the side] by its third and this third by its own fourth less the thirty-fourth part of that fourth.

Little is known with certainty about the time or circumstances of this discovery, but the name of Hippasus of Metapontum is often mentioned.

For a while, the Pythagoreans treated as an official secret the discovery that the square root of two is irrational, and, according to legend, Hippasus was murdered for divulging it, though this has little to any substantial evidence in traditional historian practice.

In ancient Roman architecture, Vitruvius describes the use of the square root of 2 progression or ad quadratum technique.

The proportion was also used to design atria by giving them a length equal to a diagonal taken from a square, whose sides are equivalent to the intended atrium's width.

; the value of the guess affects only how many iterations are required to reach an approximation of a certain accuracy.

[10] Other mathematical constants whose decimal expansions have been calculated to similarly high precision include π, e, and the golden ratio.

[12] It appeared first as a full proof in Euclid's Elements, as proposition 117 of Book X.

However, since the early 19th century, historians have agreed that this proof is an interpolation and not attributable to Euclid.

as an irreducible fraction in lowest terms, with coprime positive integers

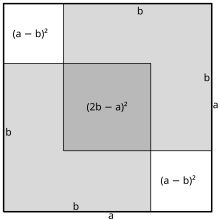

, and place two copies of the smaller square inside the larger one as shown in Figure 1.

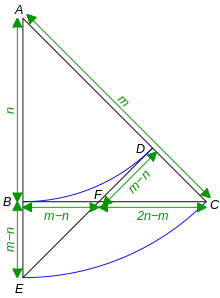

Tom M. Apostol made another geometric reductio ad absurdum argument showing that

It makes use of classic compass and straightedge construction, proving the theorem by a method similar to that employed by ancient Greek geometers.

It is essentially the same algebraic proof as in the previous paragraph, viewed geometrically in another way.

Let △ ABC be a right isosceles triangle with hypotenuse length m and legs n as shown in Figure 2.

Hence BE = m − n implies BF = m − n. By symmetry, DF = m − n, and △ FDC is also a right isosceles triangle.

While the proofs by infinite descent are constructively valid when "irrational" is defined to mean "not rational", we can obtain a constructively stronger statement by using a positive definition of "irrational" as "quantifiably apart from every rational".

Multiplying the absolute difference |√2 − a/b| by b2(√2 + a/b) in the numerator and denominator, we get[17] the latter inequality being true because it is assumed that 1<a/b< 3/2, giving a/b + √2 ≤ 3 (otherwise the quantitative apartness can be trivially established).

This gives a lower bound of 1/3b2 for the difference |√2 − a/b|, yielding a direct proof of irrationality in its constructively stronger form, not relying on the law of excluded middle.

The multiplicative inverse (reciprocal) of the square root of two is a widely used constant, with the decimal value:[20] It is often encountered in geometry and trigonometry because the unit vector, which makes a 45° angle with the axes in a plane, has the coordinates Each coordinate satisfies One interesting property of

[23] The identity cos π/4 = sin π/4 = 1/√2, along with the infinite product representations for the sine and cosine, leads to products such as and or equivalently, The number can also be expressed by taking the Taylor series of a trigonometric function.

gives The convergence of this series can be accelerated with an Euler transform, producing It is not known whether

[24] The number can be represented by an infinite series of Egyptian fractions, with denominators defined by 2n th terms of a Fibonacci-like recurrence relation a(n) = 34a(n−1) − a(n−2), a(0) = 0, a(1) = 6.

[25] The square root of two has the following continued fraction representation: The convergents p/q formed by truncating this representation form a sequence of fractions that approximate the square root of two to increasing accuracy, and that are described by the Pell numbers (i.e., p2 − 2q2 = ±1).

: In 1786, German physics professor Georg Christoph Lichtenberg[26] found that any sheet of paper whose long edge is

times longer than its short edge could be folded in half and aligned with its shorter side to produce a sheet with exactly the same proportions as the original.

[26] Today, the (approximate) aspect ratio of paper sizes under ISO 216 (A4, A0, etc.)

be the analogous ratio of the halved sheet, then There are some interesting properties involving the square root of 2 in the physical sciences: