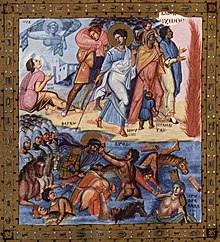

Macedonian art (Byzantine)

The court-quality pieces have, as with other periods, traditionally thought to have mostly been created in the capital, Constantinople, or made by artists based or trained there, although art historians have begun to question whether this easy assumption is entirely correct.

This situation, often referred to as "dynastic grafting," allowed these foreigners to leverage the Macedonian dynasty's legitimacy and power to further their own family's ambitions.

The following year, Basil continued the trail of Bloodshed, as he murdered Michael III, securing his position as sole emperor and successfully establishing himself as the first ruler of the dynasty.

[4] Three significant monastic churches in Greece are frequently cited as "classic" examples of the Middle Byzantine mosaic program, those being the Katholikon of Hosios Loukas, situated in the foothills of Mount Helicon west of Thebes, Nea Moni, located on the island of Chios, and the Church of the Koimesis at Daphni, near Eleusis in Attica.

[5] Nea Moni is dated to the reign of Constantine VII (1045–1054), with the emperor’s patronage linked to monks who successfully gained his support.

There was a revival of interest in classical Hellenistic styles and subjects, of which the Paris Psalter is an important testimony, and more sophisticated techniques were used to depict human figures.

The aftermath of the iconoclastic period freed Byzantine art from restrictive ecclesiastical influences and opened the door to innovative approaches.

These included a revival of early Alexandrian traditions, the incorporation of ornate Arab-inspired motifs, and a shift toward historical and secular subjects.

[6] The artistic achievements of the Macedonian dynasty reflected grace, drawn from the Hellenistic fourth century, with the strength and beauty of earlier traditions.

However, the subsequent Comnenian period brought challenges, as political and social turmoil ushered in a more rigid and less dynamic artistic expression.