Cabbage

[5] They can be prepared many different ways for eating; they can be pickled, fermented (for dishes such as sauerkraut, kimchi), steamed, stewed, roasted, sautéed, braised, or eaten raw.

Each flower has four petals set in a perpendicular pattern, as well as four sepals, six stamens, and a superior ovary that is two-celled and contains a single stigma and style.

Leaf types are generally divided between crinkled-leaf, loose-head savoys and smooth-leaf firm-head cabbages, while the color spectrum includes white and a range of greens and purples.

[10] Cabbage has been selectively bred for head weight and morphological characteristics, frost hardiness, fast growth and storage ability.

The appearance of the cabbage head has been given importance in selective breeding, with varieties being chosen for shape, color, firmness and other physical characteristics.

[22][23] The original family name of brassicas was Cruciferae, which derived from the flower petal pattern thought by medieval Europeans to resemble a crucifix.

[26] Although cabbage has an extensive history,[1] it is difficult to trace its exact origins owing to the many varieties of leafy greens classified as "brassicas".

[27] A possible wild ancestor of cabbage, Brassica oleracea, originally found in Britain and continental Europe, is tolerant of salt but not encroachment by other plants and consequently inhabits rocky cliffs in cool damp coastal habitats,[28] retaining water and nutrients in its slightly thickened, turgid leaves.

Nonheading cabbages and kale were probably the first to be domesticated, before 1000 BC,[31] perhaps by the Celts of central and western Europe,[20] although recent linguistic and genetic evidence enforces a Mediterranean origin of cultivated brassicas.

[36] Ptolemaic Egyptians knew the cole crops as gramb, under the influence of Greek krambe, which had been a familiar plant to the Macedonian antecedents of the Ptolemies.

[35] By early Roman times, Egyptian artisans and children were eating cabbage and turnips among a wide variety of other vegetables and pulses.

[41] The more traditionalist Cato the Elder, espousing a simple Republican life, ate his cabbage cooked or raw and dressed with vinegar; he said it surpassed all other vegetables, and approvingly distinguished three varieties; he also gave directions for its medicinal use, which extended to the cabbage-eater's urine, in which infants might be rinsed.

[34] According to Pliny, the Pompeii cabbage, which could not stand cold, is "taller, and has a thick stock near the root, but grows thicker between the leaves, these being scantier and narrower, but their tenderness is a valuable quality".

The Greeks and Romans claimed medicinal usages for their cabbage varieties that included relief from gout, headaches and the symptoms of poisonous mushroom ingestion.

At the end of Antiquity cabbage is mentioned in De observatione ciborum ("On the Observance of Foods") by Anthimus, a Greek doctor at the court of Theodoric the Great.

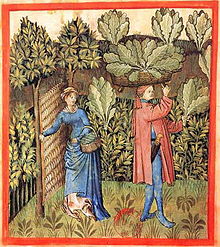

Cabbage appears among vegetables directed to be cultivated in the Capitulare de villis, composed in 771–800 AD, that guided the governance of the royal estates of Charlemagne.

[48] French naturalist Jean Ruel made what is considered the first explicit mention of head cabbage in his 1536 botanical treatise De Natura Stirpium, referring to it as capucos coles ("head-coles").

[5] Jacques Cartier first brought cabbage to the Americas in 1541–42, and it was probably planted by the early English colonists, despite the lack of written evidence of its existence there until the mid-17th century.

[55] Plants are generally started in protected locations early in the growing season before being transplanted outside, although some are seeded directly into the ground from which they will be harvested.

[60] When being grown for seed, cabbages must be isolated from other B. oleracea subspecies, including the wild varieties, by 0.8 to 1.6 km (1⁄2 to 1 mi) to prevent cross-pollination.

They are both seedborne and airborne, and typically propagate from spores in infected plant debris left on the soil surface for up to twelve weeks after harvest.

Rhizoctonia solani causes the post-emergence disease wirestem, resulting in killed seedlings ("damping-off"), root rot or stunted growth and smaller heads.

[68] The cabbage looper (Trichoplusia ni) is infamous in North America for its voracious appetite and for producing frass that contaminates plants.

[70] Destructive soil insects such as the cabbage root fly (Delia radicum) has larvae can burrow into the part of plant consumed by humans.

[64] Factors that contribute to reduced head weight include: growth in the compacted soils that result from no-till farming practices, drought, waterlogging, insect and disease incidence, and shading and nutrient stress caused by weeds.

Biological risk assessments have concluded that there is the potential for further outbreaks linked to uncooked cabbage, due to contamination at many stages of the growing, harvesting and packaging processes.

[76] Whilst not a toxic vegetable in its natural state, an increase in intestinal gas can lead to the death of many small animals like rabbits due to gastrointestinal stasis.

The simplest options include eating the vegetable raw or steaming it, though many cuisines pickle, stew, sautée or braise cabbage.

The Ancient Greeks recommended consuming the vegetable as a laxative,[49] and used cabbage juice as an antidote for mushroom poisoning,[92] for eye salves, and for liniments for bruises.

[95] The supposed cooling properties of the leaves were used in Britain as a treatment for trench foot in World War I, and as compresses for ulcers and breast abscesses.