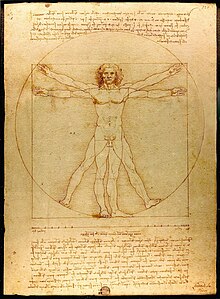

Artistic canons of body proportions

[10] By this he meant that a statue should be composed of clearly definable parts, all related to one another through a system of ideal mathematical proportions and balance.

An observation on the subject by Rhys Carpenter remains valid:[11] "Yet it must rank as one of the curiosities of our archaeological scholarship that no-one has thus far succeeded in extracting the recipe of the written canon from its visible embodiment, and compiling the commensurable numbers that we know it incorporates.

[13] In his Historia Naturalis, Pliny the Elder wrote that Lysippos introduced a new canon into art: capita minora faciendo quam antiqui, corpora graciliora siccioraque, per qum proceritassignorum major videretur,[14][b] signifying "a canon of bodily proportions essentially different from that of Polykleitos".

[17] Praxiteles (fourth century BCE), sculptor of the famed Aphrodite of Knidos, is credited with having thus created a canonical form for the female nude,[18] but neither the original work nor any of its ratios survive.

Academic study of later Roman copies (and in particular modern restorations of them) suggest that they are artistically and anatomically inferior to the original.

Each of these varies with the subject; for example, images of the three Supreme deities, Bramā, Vishnu and Śiva are required to be formed according to the set of proportions collectively called the uttama-daśa-tāla measurement; similarly, the malhyama-daśa-tāla is prescribed for images of the principal Śaktis (goddesses), Lakshmi, Bhūmi, Durgā, Pārvati and Sarasvati: the pancha-tāla, for making the figure of Gaṇapati, and the chatus-tāla for the figures of children and of deformed and dwarfed men.

The canon then, is of use as a rule of thumb, relieving him of some part of the technical difficulties, leaving him free to concentrate his thought more singly on the message or burden of his work.

He popularised the yosegi technique of sculpting a single figure out of many pieces of wood, and he redefined the canon of body proportions used in Japan to create Buddhist imagery.

[26] Modern figurative artists tend to[weasel words] use a shorthand of more comprehensive canons, based on proportions relative to the human head.