De architectura

Probably written between 30–20 BC,[4] it combines the knowledge and views of many antique writers, Greek and Roman, on architecture, the arts, natural history and building technology.

Though often cited for his famous "triad" of characteristics associated with architecture – utilitas, firmitas and venustas (utility, strength and beauty) – the aesthetic principles that influenced later treatise writers were outlined in Book III.

Derived partially from Latin rhetoric (through Cicero and Varro), Vitruvian terms for order, arrangement, proportion, and fitness for intended purposes have guided architects for centuries, and continue to do so.

For instance, in Book II of De architectura, he advises architects working with bricks to familiarise themselves with pre-Socratic theories of matter so as to understand how their materials will behave.

Likewise, Vitruvius cites Ctesibius of Alexandria and Archimedes for their inventions, Aristoxenus (Aristotle's apprentice) for music, Agatharchus for theatre, and Varro for architecture.

This quote is taken from Sir Henry Wotton's version of 1624, and accurately translates the passage in the work, (I.iii.2) but English has changed since then, especially in regard to the word "commodity", and the tag may be misunderstood.

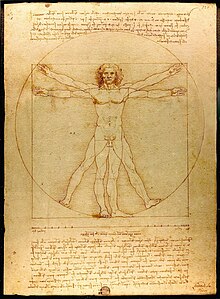

Vitruvius also studied human proportions (Book III) and this part of his canones were later adopted and adapted in the famous drawing Homo Vitruvianus ("Vitruvian Man") by Leonardo da Vinci.

Vitruvius also described the construction of sundials and water clocks, and the use of an aeolipile (the first steam engine) as an experiment to demonstrate the nature of atmospheric air movements (wind).

Books VIII, IX, and X of De architectura form the basis of much of what is known about Roman technology, now augmented by archaeological studies of extant remains, such as the Pont du Gard in southern France.

Cement, concrete, and lime received in-depth descriptions, the longevity of many Roman structures being mute testimony to their skill in building materials and design.

He comes to this conclusion in Book VIII of De architectura after empirical observation of the apparent laborer illnesses in the plumbum (lead pipe) foundries of his time.

That they were using such devices in mines clearly implies that they were entirely capable of using them as water wheels to develop power for a range of activities, not just for grinding wheat, but also probably for sawing timber, crushing ores, fulling, and so on.

He also advised using a type of regulator to control the heat in the hot rooms, a bronze disc set into the roof under a circular aperture, which could be raised or lowered by a pulley to adjust the ventilation.

They were essential in all building operations, but especially in aqueduct construction, where a uniform gradient was important to provision of a regular supply of water without damage to the walls of the channel.

He described the hodometer, in essence a device for automatically measuring distances along roads, a machine essential for developing accurate itineraries, such as the Peutinger Table.

In Book IV Chapter 1 Subsection 4 of De architectura is a description of 13 Athenian cities in Asia Minor, "the land of Caria", in present-day Turkey.

These cities are given as: Ephesus, Miletus, Myus, Priene, Samos, Teos, Colophon, Chius, Erythrae, Phocaea, Clazomenae, Lebedos, Mytilene, and later a 14th, Smyrnaeans.

The London Vitruvius (British Library, Harley 2767), the oldest surviving manuscript, includes only one of the original illustrations, a rather crudely drawn octagonal wind rose in the margin.

[12] These texts were not just copied, but also known at the court of Charlemagne, since his historian, bishop Einhard, asked the visiting English churchman Alcuin for explanations of some technical terms.

In addition, a number of individuals are known to have read the text or have been indirectly influenced by it, including: Vussin, Hrabanus Maurus, Hermann of Reichenau, Hugo of St. Victor, Gervase of Melkley, William of Malmesbury, Theodoric of Sint-Truiden, Petrus Diaconus, Albertus Magnus, Filippo Villani, Jean de Montreuil, Petrarch, Boccaccio, Giovanni de Dondi, Domenico Bandini, Niccolò Acciaioli bequeathed copy to the Basilica of San Lorenzo, Florence, Bernward of Hildesheim, and Thomas Aquinas.

[13] In 1244 the Dominican friar Vincent of Beauvais made a large number of references to De architectura in his compendium of all the knowledge of the Middle Ages Speculum Maius Many copies of De architectura, dating from the 8th to the 15th centuries, did exist in manuscript form during the Middle Ages and 92 are still available in public collections, but they appear to have received little attention, possibly due to the obsolescence of many specialized Latin terms used by Vitruvius [citation needed] and the loss of most of the original 10 illustrations thought by some to be helpful in understanding parts of the text.

Renaissance architects, such as Niccoli, Brunelleschi and Leon Battista Alberti, found in De architectura their rationale for raising their branch of knowledge to a scientific discipline as well as emphasising the skills of the artisan.

The English architect Inigo Jones and the Frenchman Salomon de Caus were among the first to re-evaluate and implement those disciplines that Vitruvius considered a necessary element of architecture: arts and sciences based upon number and proportion.