Cantor's diagonal argument

[4][5] However, it demonstrates a general technique that has since been used in a wide range of proofs,[6] including the first of Gödel's incompleteness theorems[2] and Turing's answer to the Entscheidungsproblem.

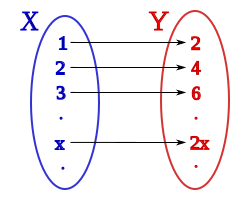

This function will be modified to produce a bijection between T and R. This construction uses a method devised by Cantor that was published in 1878.

Next observe that the linear function h(x) = πx – π/2 is a bijection from (0, 1) to (−π/2, π/2) (see the figure shown on the left).

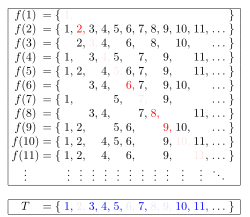

That means that some member T of P(S), i.e. some subset of S, is not in the image of f. As a candidate consider the set: For every s in S, either s is in T or not.

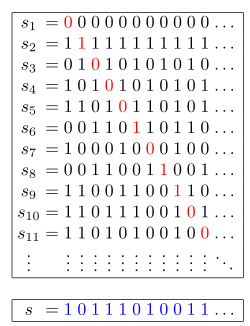

One can embed the naturals into the binary sequences, thus proving various injection existence statements explicitly, so that in this sense

But following from the argument in the previous sections, there is no surjection and so also no bijection, i.e. the set is uncountable.

" is understood to mean the existence of an injection together with the proven absence of a bijection (as opposed to alternatives such as the negation of Cantor's preorder, or a definition in terms of assigned ordinals).

Assuming the law of excluded middle, characteristic functions surject onto powersets, and then

Classically, the Schröder–Bernstein theorem is valid and says that any two sets which are in the injective image of one another are in bijection as well.

It is however harder or impossible to order ordinals and also cardinals, constructively.

Neither are most properties of interesting classes of functions decidable, by Rice's theorem, i.e. the set of counting numbers for the subcountable sets may not be recursive and can thus fail to be countable.

In an otherwise constructive context (in which the law of excluded middle is not taken as axiom), it is consistent to adopt non-classical axioms that contradict consequences of the law of excluded middle.

[11][12] This is a notion of size that is redundant in the classical context, but otherwise need not imply countability.

Consequently, also in the presence of function space sets that are even classically uncountable, intuitionists do not accept this relation to constitute a hierarchy of transfinite sizes.

[14] When the axiom of powerset is not adopted, in a constructive framework even the subcountability of all sets is then consistent.

Weaker logical axioms mean fewer constraints and so allow for a richer class of models.

The former relate to quotients of sequences while the later are well-behaved cuts taken from a powerset, if they exist.

Otherwise, variants of the Dedekind reals can be countable[15] or inject into the naturals, but not jointly.

Indeed, here choice also aids diagonal constructions and when assuming it, Cauchy-complete models of the reals are uncountable.

Similarly, the question of whether there exists a set whose cardinality is between |S| and |P(S)| for some infinite S leads to the generalized continuum hypothesis.

Russell's paradox has shown that set theory that includes an unrestricted comprehension scheme is contradictory.

Therefore, depending on how we modify the axiom scheme of comprehension in order to avoid Russell's paradox, arguments such as the non-existence of a set of all sets may or may not remain valid.

Analogues of the diagonal argument are widely used in mathematics to prove the existence or nonexistence of certain objects.

For example, the conventional proof of the unsolvability of the halting problem is essentially a diagonal argument.

Also, diagonalization was originally used to show the existence of arbitrarily hard complexity classes and played a key role in early attempts to prove P does not equal NP.

The above proof fails for W. V. Quine's "New Foundations" set theory (NF).

In NF, the naive axiom scheme of comprehension is modified to avoid the paradoxes by introducing a kind of "local" type theory.

On the other hand, we might try to create a modified diagonal argument by noticing that is a set in NF.

In which case, if P1(S) is the set of one-element subsets of S and f is a proposed bijection from P1(S) to P(S), one is able to use proof by contradiction to prove that |P1(S)| < |P(S)|.

The proof follows by the fact that if f were indeed a map onto P(S), then we could find r in S, such that f({r}) coincides with the modified diagonal set, above.