Mind–body dualism

For Aristotle, the first two souls, based on the body, perish when the living organism dies,[3][4] whereas there remains an immortal and perpetual intellective part of mind.

[6] It has been considered a form of reductionism by some philosophers, since it enables the tendency to ignore very big groups of variables by its assumed association with the mind or the body, and not for its real value when it comes to explaining or predicting a studied phenomenon.

Bodies were seen as biological organisms to be studied in their constituent parts (materialism) by means of anatomy, physiology, biochemistry and physics (reductionism).

[19][20][21][22] Emergent dualism asserts that mental substances come into existence when physical systems such as the brain reach a sufficient level of complexity.

[26] Edward Feser has written that: Aristotelians and Thomists (those philosophers whose views are derived from St.Thomas Aquinas) sometimes suggest that their hylomorphic position is no more a version of dualism than it is of materialism.

[17]Eleonore Stump has suggested that Thomas Aquinas's views on matter and the soul are difficult to define in contemporary discussion but he would fit the criteria as a non-Cartesian substance dualist.

Predicate dualists believe that so-called "folk psychology," with all of its propositional attitude ascriptions, is an ineliminable part of the enterprise of describing, explaining, and understanding human mental states and behavior.

This is a position which is very appealing to common-sense intuitions, notwithstanding the fact that it is very difficult to establish its validity or correctness by way of logical argumentation or empirical proof.

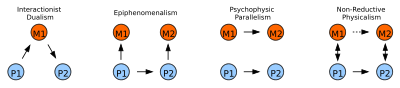

[42] Psychophysical parallelism is a very unusual view about the interaction between mental and physical events which was most prominently, and perhaps only truly, advocated by Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz.

The theory states that the illusion of efficient causation between mundane events arises out of a constant conjunction that God had instituted, such that every instance where the cause is present will constitute an "occasion" for the effect to occur as an expression of the aforementioned power.

Sextus Empiricus places him with Hesiod, Parmenides, and Empedocles, as belonging to the class of philosophers who held a dualistic theory of a material and an active principle being together the origin of the universe.

In the dialogue Phaedo, Plato formulated his famous Theory of Forms as distinct and immaterial substances of which the objects and other phenomena that we perceive in the world are nothing more than mere shadows.

[47] In the scholastic tradition of Saint Thomas Aquinas, a number of whose doctrines have been incorporated into Roman Catholic dogma, the soul is the substantial form of a human being.

[55] In his Meditations on First Philosophy, René Descartes embarked upon a quest in which he called all his previous beliefs into doubt, in order to find out what he could be certain of.

The central claim of what is often called Cartesian dualism, in honor of Descartes, is that the immaterial mind and the material body, while being ontologically distinct substances, causally interact.

Because Descartes' was such a difficult theory to defend, some of his disciples, such as Arnold Geulincx and Nicolas Malebranche, proposed a different explanation: That all mind–body interactions required the direct intervention of God.

Naturalistic dualism comes from Australian philosopher, David Chalmers (born 1966) who argues there is an explanatory gap between objective and subjective experience that cannot be bridged by reductionism because consciousness is, at least, logically autonomous of the physical properties upon which it supervenes.

[56][57] Contributors include Charles Taliaferro, Edward Feser, William Hasker, J. P. Moreland, Richard Swinburne, Lynne Rudder Baker, John W. Cooper and Timothy O'Connor.

He states that the brain is composed of two hemispheres and a cord linking the two and that, as modern science has shown, either of these can be removed without the person losing any memories or mental capacities.

[86] Similar to Anscombe, Richard Carrier and John Beversluis have written extensive objections to the argument from reason on the untenability of its first postulate.

Varieties of dualism according to which an immaterial mind causally affects the material body and vice versa have come under strenuous attack from different quarters, especially in the 20th century.

Many physicists and consciousness researchers have argued that any action of a nonphysical mind on the brain would entail the violation of physical laws, such as the conservation of energy.

[110] However, J. J. C. Smart and Paul Churchland have pointed out that if physical phenomena fully determine behavioral events, then by Occam's razor an unphysical mind is unnecessary.

For instance, Thomistic dualism doesn't obviously face any issue with regards to interaction, for in this view the soul and the body are related as form and matter.

Indeed, it is very frequently the case that one can even predict and explain the kind of mental or psychological deterioration or change that human beings will undergo when specific parts of their brains are damaged.

[115] Phineas Gage, who suffered destruction of one or both frontal lobes by a projectile iron rod, is often cited as an example illustrating that the brain causes mind.

[126] According to the philosopher Stephen Evans: We did not need neurophysiology to come to know that a person whose head is bashed in with a club quickly loses his or her ability to think or have any conscious processes.

Why should we not think of neurophysiological findings as giving us detailed, precise knowledge of something that human beings have always known, or at least could have known, which is that the mind (at least in this mortal life) requires and depends on a functioning brain?

The dualist is always faced with the question of why anyone should find it necessary to believe in the existence of two, ontologically distinct, entities (mind and brain), when it seems possible and would make for a simpler thesis to test against scientific evidence, to explain the same events and properties in terms of one.

[133][134][135] Glassen argued that, because it is not a physical entity, Occam's razor cannot consistently be appealed to by a physicalist or materialist as a justification of mental states or events, such as the belief that dualism is false.