Wheel of Fortune (medieval)

The metaphor was already a cliché in ancient times, complained about by Tacitus, but was greatly popularized for the Middle Ages by its extended treatment in the Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius from around 520.

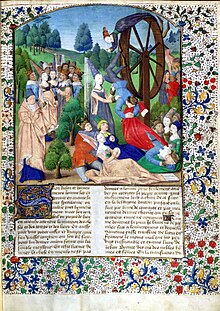

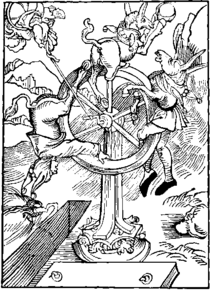

It became a common image in manuscripts of the book, and then other media, where Fortuna, often blindfolded, turns a large wheel of the sort used in watermills, to which kings and other powerful figures are attached.

Cicero wrote: “The house of your colleague rang with song and cymbals while he himself danced naked at a feast, wherein, even while he executed his whirling gyrations, he felt no fear of the Wheel of Fortune” ("cum conlegae tui domus cantu et cymbalis personaret cumque ipse nudus in convivio saltaret, in quo cum illum saltatorium versaret orbem, ne tum qui dem fortunae rotam pertimescebat").

It was widely used in the Ptolemaic perception of the universe as the zodiac being a wheel with its "signs" constantly turning throughout the year and having effect on the world's fate (or fortune).

stupid, because she can't distinguish between the worthy and the unworthy.The idea of the rolling ball of fortune became a literary topos and was used frequently in declamation.

In fact, the Rota Fortunae became a prime example of a trite topos or meme for Tacitus, who mentions its rhetorical overuse in the Dialogus de oratoribus.

In the second century AD, astronomer and astrologer Vettius Valens wrote: The goddess and her Wheel were eventually absorbed into Western medieval thought.

For example, from the first chapter of the second book: I know the manifold deceits of that monstrous lady, Fortune; in particular, her fawning friendship with those whom she intends to cheat, until the moment when she unexpectedly abandons them, and leaves them reeling in agony beyond endurance.

Though classically Fortune's Wheel could be favourable and disadvantageous, medieval writers preferred to concentrate on the tragic aspect, dwelling on downfall of the mighty – serving to remind people of the temporality of earthly things.

...fortune is so variant, and the wheel so moveable, there nis none constant abiding, and that may be proved by many old chronicles, of noble Hector, and Troilus, and Alisander, the mighty conqueror, and many mo other; when they were most in their royalty, they alighted lowest.

For instance, in most romances, Arthur's greatest military achievement – the conquest of the Roman Empire – is placed late on in the overall story.

[12] In Anthony Trollope's novel The Way We Live Now, the character Lady Carbury writes a novel entitled The Wheel of Fortune about a heroine who suffers great financial hardships.