Cartesian materialism

Contrary to its name, Cartesian materialism is not a view that was held by or formulated by René Descartes, who subscribed rather to a form of substance dualism.

French materialism developed from the mechanism of Descartes and the empiricism of Locke, Hobbes, Bacon and ultimately Duns Scotus who asked "Whether matter could not think?"

Natural science, in their view, owes to the former its great success as a "Cartesian materialism", bereft of the metaphysics of Cartesian dualism by philosophers and physicians such as Regius, Cabanis, and La Mettrie, who maintained the viability of Descartes' biological automata without recourse to immaterial cognition.

However, philosopher Daniel Dennett uses the term to emphasize what he considers the pervasive Cartesian notion of a centralized repository of conscious experience in the brain.

"[3] However, although Rockwell's concept of Cartesian materialism is less specific in a sense, it is a detailed reply to Dennett's version, not an undeveloped predecessor.

The main theme of Rockwell's book Neither Brain nor Ghost is that the arguments Dennett uses to refute his version of Cartesian materialism actually support the view that the mind is an emergent property of the entire Brain/Body/World Nexus.

[citation needed] Descartes believed that a human being was composed of both a material body and an immaterial soul (or "mind").

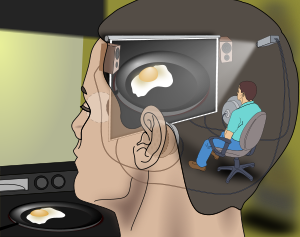

Based on this, Descartes hypothesized that there must be some single place in the brain where all the sensory information is assembled, before finally being relayed to the immaterial mind.

At the present time, the consensus of scientists and philosophers is to reject dualism and its immaterial mind, for a variety of reasons.

Similarly, many other aspects of Descartes' theories have been rejected; for example, the pineal gland turned out to be endocrinological, rather than having a large role in information processing.

According to Daniel Dennett, however, many scientists and philosophers still believe, either explicitly or implicitly, in Descartes' idea of some centralized repository where the contents of consciousness are merged and assembled, a place he calls the Cartesian theater.

In his book Consciousness Explained (1991), Dennett writes: Although this central repository is often called a "place" or a "location", Dennett is quick to clarify that Cartesian materialism's "centered locus" need not be anatomically defined-- such a locus might consists of a network of diverse regions.

In experiments that demonstrate the Color Phi phenomenon and the metacontrast effect, two stimuli are rapidly flashed on a screen, one after the other.

Dennett calls this the "Stalinesque Explanation" (after the Stalinist Soviet Union's show trials that presented manufactured evidence to an unwitting jury).

Dennett calls this view the "Orwellian Explanation", after George Orwell's novel 1984, in which a totalitarian government frequently rewrites history to suit its purposes.

Cartesian materialism, it is alleged, is an impossibly naive account of phenomenal consciousness held by no one currently working in cognitive science or the philosophy of mind.

(Michael Tye) On the other hand, some say that Cartesian materialism "informs virtually all research on mind and brain, explicitly and implicitly" (Antonio Damasio) or argue that the common "commitment to qualia or 'phenomenal seemings'" entails an implicit commitment to Cartesian materialism that becomes explicit when they "work out a theory of consciousness in sufficient detail".

[11] Despite Dennett's insistence that there are no special brain areas that store the contents of consciousness, many neuroscientists reject this assertion.