Catenary

In physics and geometry, a catenary (US: /ˈkætənɛri/ KAT-ən-err-ee, UK: /kəˈtiːnəri/ kə-TEE-nər-ee) is the curve that an idealized hanging chain or cable assumes under its own weight when supported only at its ends in a uniform gravitational field.

The curve appears in the design of certain types of arches and as a cross section of the catenoid—the shape assumed by a soap film bounded by two parallel circular rings.

[4] Galileo Galilei in 1638 discussed the catenary in the book Two New Sciences recognizing that it was different from a parabola.

The mathematical properties of the catenary curve were studied by Robert Hooke in the 1670s, and its equation was derived by Leibniz, Huygens and Johann Bernoulli in 1691.

Catenaries and related curves are used in architecture and engineering (e.g., in the design of bridges and arches so that forces do not result in bending moments).

In the rail industry it refers to the overhead wiring that transfers power to trains.

In optics and electromagnetics, the hyperbolic cosine and sine functions are basic solutions to Maxwell's equations.

The English word "catenary" is usually attributed to Thomas Jefferson,[9][10] who wrote in a letter to Thomas Paine on the construction of an arch for a bridge: I have lately received from Italy a treatise on the equilibrium of arches, by the Abbé Mascheroni.

I have not yet had time to engage in it; but I find that the conclusions of his demonstrations are, that every part of the catenary is in perfect equilibrium.

[13] The fact that the curve followed by a chain is not a parabola was proven by Joachim Jungius (1587–1657); this result was published posthumously in 1669.

[15] In 1671, Hooke announced to the Royal Society that he had solved the problem of the optimal shape of an arch, and in 1675 published an encrypted solution as a Latin anagram[16] in an appendix to his Description of Helioscopes,[17] where he wrote that he had found "a true mathematical and mechanical form of all manner of Arches for Building."

He did not publish the solution to this anagram[18] in his lifetime, but in 1705 his executor provided it as ut pendet continuum flexile, sic stabit contiguum rigidum inversum, meaning "As hangs a flexible cable so, inverted, stand the touching pieces of an arch."

[19][20] David Gregory wrote a treatise on the catenary in 1697[12][21] in which he provided an incorrect derivation of the correct differential equation.

[1] Nicolas Fuss gave equations describing the equilibrium of a chain under any force in 1796.

[23][24] The Gateway Arch in St. Louis, Missouri, United States is sometimes said to be an (inverted) catenary, but this is incorrect.

In most cases the roadway is flat, so when the weight of the cable is negligible compared with the weight being supported, the force exerted is uniform with respect to horizontal distance, and the result is a parabola, as discussed below (although the term "catenary" is often still used, in an informal sense).

When the rope is slack, the catenary curve presents a lower angle of pull on the anchor or mooring device than would be the case if it were nearly straight.

To maintain the catenary shape in the presence of wind, a heavy chain is needed, so that only larger ships in deeper water can rely on this effect.

[37] Cable ferries and chain boats present a special case of marine vehicles moving although moored by the two catenaries each of one or more cables (wire ropes or chains) passing through the vehicle and moved along by motorized sheaves.

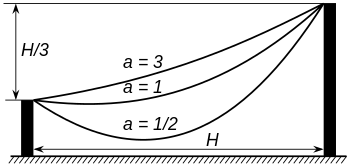

where cosh is the hyperbolic cosine function, and where a is the distance of the lowest point above the x axis.

[41] When a parabola is rolled along a straight line, the roulette curve traced by its focus is a catenary.

This implies that square wheels can roll perfectly smoothly on a road made of a series of bumps in the shape of an inverted catenary curve.

Let the path followed by the chain be given parametrically by r = (x, y) = (x(s), y(s)) where s represents arc length and r is the position vector.

The tension at c is tangent to the curve at c and is therefore horizontal without any vertical component and it pulls the section to the left so it may be written (−T0, 0) where T0 is the magnitude of the force.

Since the primary interest here is simply the shape of the curve, the placement of the coordinate axes are arbitrary; so make the convenient choice of

The equation can be determined in this case as follows:[56] Relabel if necessary so that P1 is to the left of P2 and let H be the horizontal and v be the vertical distance from P1 to P2.

The horizontal traction force at P1 and P2 is T0 = wa, where w is the weight per unit length of the chain or cable.

A similar analysis can be done to find the curve followed by the cable supporting a suspension bridge with a horizontal roadway.

[62] In a catenary of equal strength, the cable is strengthened according to the magnitude of the tension at each point, so its resistance to breaking is constant along its length.

These equations can be used as the starting point in the analysis of a flexible chain acting under any external force.

![{\displaystyle y=x^{2}[({\text{cosh }}1)-1]+1}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ad50cad095170c986635e7c1d1100bf1e3cd8385)