Cathay

[4] In about 1340 Francesco Balducci Pegolotti, a merchant from Florence, compiled the Pratica della mercatura, a guide about trade in China, a country he called Cathay, noting the size of Khanbaliq (modern Beijing) and how merchants could exchange silver for Chinese paper money that could be used to buy luxury items such as silk.

The ethnonym derived from Khitay in the Uyghur language for Han Chinese is considered pejorative by both its users and its referents, and the PRC authorities have attempted to ban its use.

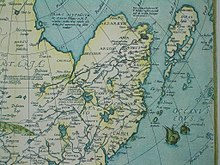

[9] As European and Arab travelers started reaching the Mongol Empire, they described the Mongol-controlled Northern China as Cathay in a number of spelling variants.

It was a small group of Jesuits, led by Matteo Ricci who, being able both to travel throughout China and to read, learned about the country from Chinese books and from conversation with people of all walks of life.

Ricci supported his arguments by numerous correspondences between Marco Polo's accounts and his own observations: Most importantly, when the Jesuits first arrived to Beijing 1598, they also met a number of "Mohammedans" or "Arabian Turks" – visitors or immigrants from the Muslim countries to the west of China, who told Ricci that now they were living in the Great Cathay.

[15] China-based Jesuits promptly informed their colleagues in Goa (Portuguese India) and Europe about their discovery of the Cathay–China identity.

[17][18] In retrospect, the Central Asian Muslim informants' idea of the Ming China being a heavily Christian country may be explained by numerous similarities between Christian and Buddhist ecclesiastical rituals – from having sumptuous statuary and ecclesiastical robes to Gregorian chant – which would make the two religions appear externally similar to a Muslim merchant.

To resolve the China–Cathay controversy, the India Jesuits sent a Portuguese lay brother, Bento de Góis, on an overland expedition north and east, with the goal of reaching Cathay and finding out once and for all whether it is China or some other country.

Góis spent almost three years (1603–1605) crossing Afghanistan, Badakhshan, Kashgaria, and Kingdom of Cialis with Muslim trade caravans.

De Góis died in Suzhou, Gansu – the first Ming China city he reached – while waiting for an entry permit to proceed toward Beijing; but, in the words of Henry Yule, it was his expedition that made "Cathay... finally disappear from view, leaving China only in the mouths and minds of men".

Samuel Purchas, who in 1625 published an English translation of Pantoja's letter and Ricci's account, thought that perhaps Cathay still can be found somewhere north of China.

[21] The last nail into the coffin of the idea of there being a Cathay as a country separate from China was, perhaps, driven in 1654, when the Dutch Orientalist Jacobus Golius met with the China-based Jesuit Martino Martini, who was passing through Leyden.

In Javanese, the word ꦏꦠꦻ (Katai, Katé) exists,[27] and it refers to "East Asian", literally meaning "dwarf" or "short-legged" in today's language.

Ezra Pound's Cathay (1915) is a collection of classical Chinese poems translated freely into English verse.

In Robert E. Howard's Hyborian Age stories (including the tales of Conan the Barbarian), the analog of China is called Khitai.

) appears on all the territory.

[

1

]

[

2

]

) appears on all the territory.

[

1

]

[

2

]