Cayley–Klein metric

The construction originated with Arthur Cayley's essay "On the theory of distance"[1] where he calls the quadric the absolute.

The field of non-Euclidean geometry rests largely on the footing provided by Cayley–Klein metrics.

The algebra of throws by Karl von Staudt (1847) is an approach to geometry that is independent of metric.

The idea was to use the relation of projective harmonic conjugates and cross-ratios as fundamental to the measure on a line.

[12][13] Klein (1871, 1873) removed the last remnants of metric concepts from von Staudt's work and combined it with Cayley's theory, in order to base Cayley's new metric on logarithm and the cross-ratio as a number generated by the geometric arrangement of four points.

[16] Cayley–Klein geometry is the study of the group of motions that leave the Cayley–Klein metric invariant.

Indeed, cross-ratio is invariant under any collineation, and the stable absolute enables the metric comparison, which will be equality.

Similarly, the real line is the absolute of the Poincaré half-plane model.

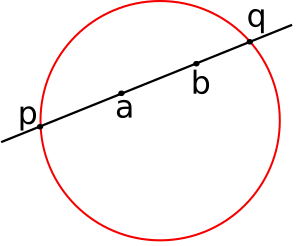

Such a homography induces one on P(R), and since p and q stay on K, the cross ratio remains invariant.

On the other hand, geodesics are arcs of generalized circles in the disk of the complex plane.

This class of curves is permuted by Möbius transformations, the source of the motions of this disk that leave the unit circle as an invariant set.

In his lectures on the history of mathematics from 1919/20, published posthumously 1926, Klein wrote:[19] That is, the absolutes

in relativity, which are bounded by the speed of light c, so that for any physical velocity v, the ratio v/c is confined to the interior of a unit sphere, and the surface of the sphere forms the Cayley absolute for the geometry.

[21] In 2008 Horst Martini and Margarita Spirova generalized the first of Clifford's circle theorems and other Euclidean geometry using affine geometry associated with the Cayley absolute: Use homogeneous coordinates (x,y,z).

A rectangular hyperbola in the (x,y) plane is considered to pass through P and Q on the line at infinity.

The question recently arose in conversation whether a dissertation of 2 lines could deserve and get a Fellowship.

... Cayley's projective definition of length is a clear case if we may interpret "2 lines" with reasonable latitude.

Arthur Cayley (1859) defined the "absolute" upon which he based his projective metric as a general equation of a surface of second degree in terms of homogeneous coordinates:[1] The distance between two points is then given by In two dimensions with the distance of which he discussed the special case

for two elements, he defined the metrical distance between them in terms of the cross ratio:

[24] The transformations leaving invariant this form represent motions in the respective non–Euclidean space.

[25] In space, he discussed fundamental surfaces of second degree, according to which imaginary ones refer to elliptic geometry, real and rectilinear ones correspond to a one-sheet hyperboloid with no relation to one of the three main geometries, while real and non-rectilinear ones refer to hyperbolic space.

In his 1873 paper he pointed out the relation between the Cayley metric and transformation groups.

[26] In particular, quadratic equations with real coefficients, corresponding to surfaces of second degree, can be transformed into a sum of squares, of which the difference between the number of positive and negative signs remains equal (this is now called Sylvester's law of inertia).

If one sign differs from the others, the surface becomes an ellipsoid or two-sheet hyperboloid with negative curvature.

and discussed their invariance with respect to collineations and Möbius transformations representing motions in non-Euclidean spaces.

In the second volume containing the lectures of the summer semester 1890 (also published 1892/1893), Klein discussed non-Euclidean space with the Cayley metric[28]

[31] He eventually discussed their invariance with respect to collineations and Möbius transformations representing motions in Non-Euclidean spaces.

Robert Fricke and Klein summarized all of this in the introduction to the first volume of lectures on automorphic functions in 1897, in which they used

[32] Klein's lectures on non-Euclidean geometry were posthumously republished as one volume and significantly edited by Walther Rosemann in 1928.

[9] An historical analysis of Klein's work on non-Euclidean geometry was given by A'Campo and Papadopoulos (2014).