Cement kiln

Successive chemical reactions take place as the temperature of the rawmix rises: Alite is the characteristic constituent of Portland cement.

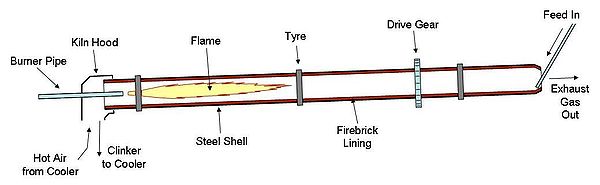

In the cooler the air is heated by the cooling clinker, so that it may be 400 to 800 °C before it enters the kiln, thus causing intense and rapid combustion of the fuel.

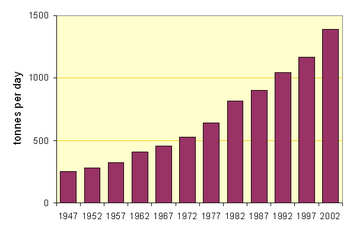

The earliest successful rotary kilns were developed in Pennsylvania around 1890, based on a design by Frederick Ransome,[5] and were about 1.5 m in diameter and 15 m in length.

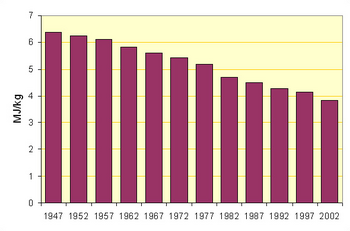

[6] The wet process suffered the obvious disadvantage that, when the slurry was introduced into the kiln, a large amount of extra fuel was used in evaporating the water.

In the dry process, it is very difficult to keep the fine powder rawmix in the kiln, because the fast-flowing combustion gases tend to blow it back out again.

Before the energy crisis of the 1970s put an end to new wet-process installations, kilns as large as 5.8 x 225 m in size were making 3000 tonnes per day.

The hot feed that leaves the base of the preheater string is typically 20% calcined, so the kiln has less subsequent processing to do, and can therefore achieve a higher specific output.

Indeed, cement with a too high alkali content can cause a harmful alkali–silica reaction (ASR) in concrete made with aggregates containing reactive amorphous silica.

The ultimate development is the "air-separate" precalciner, in which the hot combustion air for the calciner arrives in a duct directly from the cooler, bypassing the kiln.

Special techniques are required to store the fine fuel safely, and coals with high volatiles are normally milled in an inert atmosphere (e.g. CO2).

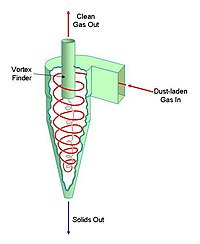

Environmental regulations specific to different countries require that this be reduced to (typically) 0.1 gram per cubic metre, so dust capture needs to be at least 99.7% efficient.

The steel and zinc in the tires become chemically incorporated into the clinker, partially replacing iron that must otherwise be fed as raw material.

If carbon monoxide is formed, this represents a waste of fuel, and also indicates reducing conditions within the kiln which must be avoided at all costs since it causes destruction of the clinker mineral structure.

Contact temperature measurement is impossible because of the chemically aggressive and abrasive nature of the hot clinker, and optical methods such as infrared pyrometry are difficult because of the dust and fume-laden atmosphere in the burning zone.

Emissions from cement works are determined both by continuous and discontinuous measuring methods, which are described in corresponding national guidelines and standards.

While particulate emissions of up to 3,000 mg/m3 were measured leaving the stack of cement rotary kiln plants as recently as in the 1960s, legal limits are typically 30 mg/m3 today, and much lower levels are achievable.

Technically, staged combustion and Selective Non-Catalytic NO Reduction (SNCR) are applied to cope with the emission limit values.

The CO then reduces the NO into molecular nitrogen: Hot tertiary air is then added to oxidize the remaining CO. Sulfur is input into the clinker burning process via raw materials and fuels.

The exhaust gas concentrations of CO and organically bound carbon are a yardstick for the burn-out rate of the fuels utilised in energy conversion plants, such as power stations.

In case of the clinker burning process, the content of CO and organic trace gases in the clean gas therefore may not be directly related to combustion conditions.

[21] Rotary kilns of the cement industry and classic incineration plants mainly differ in terms of the combustion conditions prevailing during clinker burning.

Thus, temperature distribution and residence time in rotary kilns afford particularly favourable conditions for organic compounds, introduced either via fuels or derived from them, to be completely destroyed.

For that reason, only very low concentrations of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans (colloquially "dioxins and furans") can be found in the exhaust gas from cement rotary kilns.

[citation needed] PAHs (according to EPA 610) in the exhaust gas of rotary kilns usually appear at a distribution dominated by naphthalene, which accounts for a share of more than 90% by mass.

As a rule benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene are present in the exhaust gas of rotary kilns in a characteristic ratio.

A bypass at the kiln inlet allows effective reduction of alkali chloride cycles and to diminish coating build-up problems.

Ultra-fine dust fractions that pass through the measuring gas filter may give the impression of low contents of gaseous fluorine compounds in rotary kiln systems of the cement industry.

Depending on the volatility and the operating conditions, this may result in the formation of cycles that are either restricted to the kiln and the preheater or include the combined drying and grinding plant as well.

Trace elements from the fuels initially enter the combustion gases, but are emitted to an extremely small extent only owing to the retention capacity of the kiln and the preheater.

Elements such as lead and cadmium preferentially react with the excess chlorides and sulfates in the section between the rotary kiln and the preheater, forming volatile compounds.