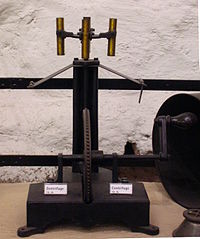

Centrifuge

Industrial scale centrifuges are commonly used in manufacturing and waste processing to sediment suspended solids, or to separate immiscible liquids.

Large centrifuges are used to simulate high gravity or acceleration environments (for example, high-G training for test pilots).

English military engineer Benjamin Robins (1707–1751) invented a whirling arm apparatus to determine drag.

[10] Other open hardware designs use custom 3-D printed fixtures with inexpensive electric motors to make low-cost centrifuges (e.g. the Dremelfuge that uses a Dremel power tool) or CNC cut out OpenFuge.

[11][12][13][14] A wide variety of laboratory-scale centrifuges are used in chemistry, biology, biochemistry and clinical medicine for isolating and separating suspensions and immiscible liquids.

Ultracentrifuges spin the rotors under vacuum, eliminating air resistance and enabling exact temperature control.

Zonal rotors and continuous flow systems are capable of handing bulk and larger sample volumes, respectively, in a laboratory-scale instrument.

The centrifuge at Brooks City Base is operated by the United States Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine for the purpose of training and evaluating prospective fighter pilots for high-g flight in Air Force fighter aircraft.

[18] The use of large centrifuges to simulate a feeling of gravity has been proposed for future long-duration space missions.

Exposure to this simulated gravity would prevent or reduce the bone decalcification and muscle atrophy that affect individuals exposed to long periods of freefall.

Experiments performed in this facility ranged from zebra fish, metal alloys, plasma,[21] cells,[22] liquids, Planaria,[23] Drosophila[24] or plants.

Problems such as building and bridge foundations, earth dams, tunnels, and slope stability, including effects such as blast loading and earthquake shaking.

[27] High gravity conditions generated by centrifuge are applied in the chemical industry, casting, and material synthesis.

[28] Protocols for centrifugation typically specify the amount of acceleration to be applied to the sample, rather than specifying a rotational speed such as revolutions per minute.

The acceleration is measured in multiples of "g" (or × "g"), the standard acceleration due to gravity at the Earth's surface, a dimensionless quantity given by the expression: where This relationship may be written as or where To avoid having to perform a mathematical calculation every time, one can find nomograms for converting RCF to rpm for a rotor of a given radius.