Circular motion

The rotation around a fixed axis of a three-dimensional body involves the circular motion of its parts.

The equations of motion describe the movement of the center of mass of a body, which remains at a constant distance from the axis of rotation.

Examples of circular motion include: special satellite orbits around the Earth (circular orbits), a ceiling fan's blades rotating around a hub, a stone that is tied to a rope and is being swung in circles, a car turning through a curve in a race track, an electron moving perpendicular to a uniform magnetic field, and a gear turning inside a mechanism.

Without this acceleration, the object would move in a straight line, according to Newton's laws of motion.

Since the body describes circular motion, its distance from the axis of rotation remains constant at all times.

This acceleration is, in turn, produced by a centripetal force which is also constant in magnitude and directed toward the axis of rotation.

In the case of rotation around a fixed axis of a rigid body that is not negligibly small compared to the radius of the path, each particle of the body describes a uniform circular motion with the same angular velocity, but with velocity and acceleration varying with the position with respect to the axis.

With this convention for depicting rotation, the velocity is given by a vector cross product as

Consider a body of one kilogram, moving in a circle of radius one metre, with an angular velocity of one radian per second.

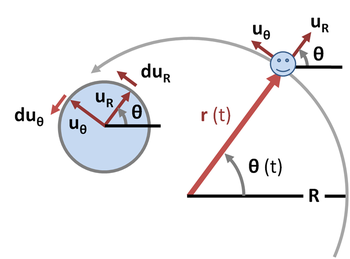

During circular motion, the body moves on a curve that can be described in the polar coordinate system as a fixed distance R from the center of the orbit taken as the origin, oriented at an angle θ(t) from some reference direction.

If the particle displacement rotates through an angle dθ in time dt, so does

is the argument of the complex number as a function of time, t. Since the radius is constant:

The first term is opposite in direction to the displacement vector and the second is perpendicular to it, just like the earlier results shown before.

Figure 1 illustrates velocity and acceleration vectors for uniform motion at four different points in the orbit.

For a path of radius r, when an angle θ is swept out, the distance traveled on the periphery of the orbit is s = rθ.

and the square of proper acceleration, expressed as a scalar invariant, the same in all reference frames,

or, taking the positive square root and using the three-acceleration, we arrive at the proper acceleration for circular motion:

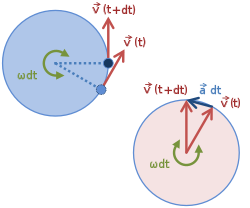

The left-hand circle in Figure 2 is the orbit showing the velocity vectors at two adjacent times.

Because speed is constant, the velocity vectors on the right sweep out a circle as time advances.

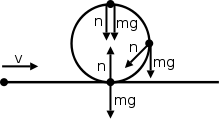

In non-uniform circular motion, the normal force does not always point to the opposite direction of weight.

Both forces can point downwards, yet the object will remain in a circular path without falling down.

From a logical standpoint, a person travelling in that plane will be upside down at the top of the circle.

A varying angular speed for an object moving in a circular path can also be achieved if the rotating body does not have a homogeneous mass distribution.

[2] One can deduce the formulae of speed, acceleration and jerk, assuming that all the variables to depend on

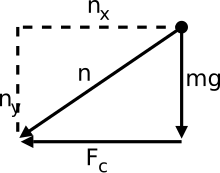

Solving applications dealing with non-uniform circular motion involves force analysis.

In a non-uniform circular motion, there are additional forces acting on the object due to a non-zero tangential acceleration.

Tangential acceleration is not used in calculating total force because it is not responsible for keeping the object in a circular path.

, we can draw free body diagrams to list all the forces acting on an object and then set it equal to

Afterward, we can solve for whatever is unknown (this can be mass, velocity, radius of curvature, coefficient of friction, normal force, etc.).

Due to the presence of tangential acceleration in a non uniform circular motion, that does not hold true any more.