Cephalopod size

[10] Tales of giant squid have been common among mariners since ancient times, and may have inspired the monstrous kraken of Nordic legend, said to be as large as an island and capable of engulfing and sinking any ship.

In squids, total length is inclusive of the feeding tentacles, which in some species may be longer than the mantle, head, and arms combined (chiroteuthids such as Asperoteuthis acanthoderma being a prime example).

It can also vary widely depending on the state of the specimen at the time of weighing (for example, whether it was measured live or dead, wet or dry, frozen or thawed, pre- or post-fixation, with or without egg mass, and so on).

[2] The smallest adult size among living cephalopods is attained by the so-called pygmy squids, Idiosepius,[32] and certain diminutive species of the genus Octopus, both of which weigh less than 1 gram (0.035 oz) at maturity.

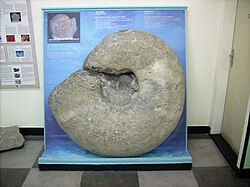

Cephalopods of comparable size to the largest present day squid are known from fossil remains, including enormous examples of ammonoids, belemnoids, nautiloids, orthoceratoids, teuthids, and vampyromorphids.

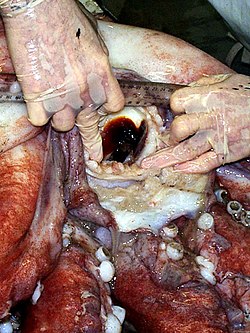

[43] Though a substantial number of colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni) remains have been recorded (Xavier et al., 1999 collated 188 geographical positions for whole or partial specimens caught by commercial and scientific fisheries), very few adult or subadult animals have ever been documented, making it difficult to estimate the maximum size of the species.

[89] Teichert & Kummel (1960:6) suggested an even larger original shell diameter of around 3.5 m (11 ft) for this specimen, assuming the body chamber extended for three-fourths to one full whorl.

[108] Reports of giant squid (Architeuthis dux) specimens reaching or even exceeding 18 m (59 ft) in total length are widespread, but no animals approaching this size have been scientifically documented in recent times.

[53] It is now thought likely that such lengths were achieved by great lengthening of the two long feeding tentacles, analogous to stretching elastic bands, or resulted from inadequate measurement methods such as pacing.

[57] On the subject of the oft-cited maximum size of 18 metres—or 60 feet—Dery (2013) quoted giant squid experts Steve O'Shea and Clyde Roper: If this figure [45 ft or 14 m] seems a little short of the Brobdingnagian claims made for Architeuthis in most pop-science stories about the animal, that's probably because virtually every general-interest article dutifully repeats the magic number of 60 feet.

I have examined specimens in museums and laboratories around the world—perhaps a 100 or so—and I believe the 60-foot number comes from fear, fantasy, and pulling the highly elastic tentacles out to the near breaking point when they are measured on the shore or on deck.

[nb 8] Paxton added: "A 4.5 m [15 ft] specimen from Mauritius is often mistakenly cited but consultation of the primary paper (Staub, 1993) reveals an ill-defined length which is clearly not ML."

Paxton treated these last two size estimates as SLs as opposed to TLs because "squid do not generally leave their tentacles exposed except when grabbing prey and this appears to be the case for Architeuthis".

Berzin's (1972) Indian Ocean claim is suspect because of the roundness of the figure, the lack of detailed measurements and because in an associated photo, the mantle (whose length was not given) does not look very large compared to the men in the image.

[120] Paxton considered the "longest visually estimated" TL to be the 60 ft (18 m) published by Murray (1874:121), from an eyewitness account by fisherman Theophilus Picot, who claimed to have struck the floating animal from his boat, causing it to attack.

Based on a detailed examination of a number of large specimens from New Zealand waters, Förch (1998:55) wrote that "[t]he largest suckers [...] on the sessile arms are a very constant 21–24 millimetres [0.83–0.94 in] in external diameter".

In giant squid the largest suckers of all are found on the central portion of the tentacular club, called the manus, and among the specimens examined by Förch (1998:53) these reached a maximum diameter of 28–32 mm (1.10–1.26 in).

Since there is a cubic relationship between the linear dimensions of Architeuthis and its volume or weight, this means the Thimble Tickle monster must have scaled about 2.8 tonnes [6,200 lb] (i.e. the weight of a large bull hippopotamus), although 2 tonnes [4,400 lb] is probably a more realistic figure.The maximum size of the giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) has long been a source of debate in the scientific community, with dubious reports of specimens weighing hundreds of kilograms.

It would appear that octopuses weighing as much as 272 kg (600 lb) and with radial spans of over nine metres (30 feet) are within the realm of possibility, but have never actually been documented by both measuring and weighing.No specimens approaching these extreme sizes have been reported since the middle of the 20th century.

This lack of giant individuals is corroborated by commercial octopus fishers; none of those interviewed by Cosgrove & McDaniel (2009) had caught a single animal weighing more than 57 kg (126 lb) in the previous 20 years, among many thousands harvested over that period.

In particular, high concentrations of heavy metals and PCBs have been identified in the digestive glands of wild giant Pacific octopuses, likely originating from their preferred prey, the red rock crab (Cancer productus).

Additionally, females of the octopus genus Argonauta secrete a specialised paper-thin eggcase in which they reside, and this is popularly regarded as a "shell", although it is not attached to the body of the animal (see Finn, 2013).

Early last month Mr. Smith, a local fisherman, brought to the [Colonial] Museum the beak and buccal-mass of a cuttle which had that morning been found lying on the "Big Beach" (Lyall Bay), and he assured us that the creature measured sixty-two feet [18.9 m] in total length.

I that afternoon proceeded to the spot and made a careful examination, took notes, measurements, and also obtained a sketch, which, although the terribly heavy rain and driving southerly wind rendered it impossible to do justice to the subject, will, I trust, convey to you some idea of the general outline of this most recently-arrived Devil-fish.

Wood (1982:191) suggested that, due to the tentacles' highly retractile nature, the total length of 62 feet (18.9 m) originally reported by the fisherman "may have been correct at the time he found the squid", and that "[t]his probably also explains the discrepancy in Kirk's figures".

I lost no time in proceeding to the spot, determined, if possible, to carry home the entire specimen; but judge my surprise when, on reaching the bay, I saw an animal of the size represented in the drawing now before you.

19; see Verrill, 1880a:192], was cast ashore, was out in a boat with two other men; not far from the shore they observed some bulky object, and, supposing it might be part of a wreck, they rowed toward it, and, to their horror, found themselves close to a huge fish, having large glassy eyes, which was making desperate efforts to escape, and churning the water into foam by the motion of its immense arms and tail.

From the funnel at the back of its head it was ejecting large volumes of water, this being its method of moving backward, the force of the stream, by the reaction of the surrounding medium, driving it in the required direction.

Finding the monster partially disabled, the fishermen plucked up courage and ventured near enough to throw the grapnel of their boat, the sharp flukes of which, having barbed points, sunk into the soft body.

But Steve O'Shea commented: The late, great Kir Nesis was not one to exaggerate, and must have had very good reason to cite a possible mantle length of 2.7m [8.9 ft] for Galiteuthis phyllura.