Ceratosaurus

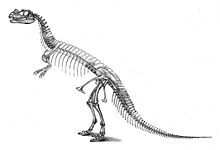

The genus was first described in 1884 by American paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh based on a nearly complete skeleton discovered in Garden Park, Colorado, in rocks belonging to the Morrison Formation.

[2]: 7, 114 After excavation, the specimen was shipped to the Peabody Museum of Natural History in New Haven, where it was studied by Marsh, who described it as the new genus and species Ceratosaurus nasicornis in 1884.

This error was repeated in several subsequent publications, including the first life reconstruction, which was drawn in 1899 by Frank Bond under the guidance of Charles R. Knight, but not published until 1920.

[7]: 276 Inspired by the upper thigh bones, which were found angled against the lower leg, he depicted the mount as a running animal with a horizontal posture and a tail that did not make contact with the ground.

[8][9] In the new exhibition, which was set to open in 2019, the mount was planned to be replaced by a free-standing cast and the original bones were to be stored in the museum collection to allow full access for scientists.

[9] After the discovery of the holotype of C. nasicornis, a significant Ceratosaurus find was not made until the early 1960s, when paleontologist James Madsen and his team unearthed a fragmentary, disarticulated skeleton including the skull (UMNH VP 5278) in the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry of Utah.

[12] Oliver Rauhut, in 2003, and Matthew Carrano and Scott Sampson, in 2008, considered the anatomical differences cited by Madsen and Welles to support these additional species to represent ontogenetic (age-related) or individual variation.

The specimen, considered the largest known from the genus, includes the front half of a skull, seven fragmentary pelvic dorsal vertebrae, and an articulated pelvis and sacrum.

Another specimen stems from the Dry Mesa Quarry of Colorado and includes a left scapulocoracoid, as well as fragments of vertebrae and limb bones.

[20]: 53 The most distinctive feature was a prominent horn situated on the skull midline behind the bony nostrils, which was formed from fused protuberances of the left and right nasal bones.

[14]: 192 In addition to the large nasal horn, Ceratosaurus possessed smaller, semicircular, bony ridges in front of each eye, similar to those of Allosaurus.

The sacrum, consisting of six fused sacral vertebrae, was arched upwards, with its vertebral centra strongly reduced in height in its middle portion, as is the case in some other ceratosaurians.

[3][2]: 115 The tail was deep from top to bottom due to its high neural spines and elongated chevrons, bones located below the vertebral centra.

As in other dinosaurs, it counterbalanced the body and contained the massive caudofemoralis muscle, which was responsible for forward thrust during locomotion, pulling the upper thigh backwards when contracted.

[14]: 187 [37] Oliver Rauhut, in 2004, proposed Genyodectes as the sister taxon of Ceratosaurus, as both genera are characterized by exceptionally long teeth in the upper jaw.

In a subsequent 2018 study, Rafael Delcourt accepted these results, but pointed out that, as a consequence, Abelisauroidea would need to be replaced by the older synonym Ceratosauroidea, which was hitherto rarely used.

These authors also noted that the nasal horn is incompletely preserved, opening the possibility that it represented the foremost portion of a more extensive head crest, as seen in some other proceratosaurids such as Guanlong.

[42] Within the Morrison and Lourinhã Formation, Ceratosaurus fossils are frequently found in association with those of other large theropods, including the megalosaurid Torvosaurus[43] and the allosaurid Allosaurus.

[47] Furthermore, the skull of USNM 4734 from the Garden Park locality, which formed the basis for Henderson's analysis of the short-snouted morph, was later found to have been reconstructed too short.

[45] However, this theory was challenged by Yun in 2019, suggesting Ceratosaurus was merely more capable of hunting aquatic prey than other theropods of the Morrison Formation as opposed to being fully semiaquatic.

[52] A bone assemblage in the Upper Jurassic Mygatt-Moore Quarry preserves an unusually high occurrence of theropod bite marks, most of which can be attributed to Allosaurus and Ceratosaurus, while others could have been made by a large allosaurid or Torvosaurus given the size of the striations.

The semicircular canals, which are responsible for the sense of balance and therefore allow for inferences on habitual head orientation and locomotion, are similar to those found in other theropods.

[57] Marsh, in 1884, dedicated a short article to this, at the time, unknown feature in dinosaurs, noting the close resemblance to the condition seen in modern birds.

[57] Other reports of pathologies include a stress fracture in a foot bone assigned to the genus,[58] as well as a broken tooth of an unidentified species of Ceratosaurus that shows signs of further wear received after the break.

[57] All North American Ceratosaurus finds come from the Morrison Formation, a sequence of shallow marine and (predominantly) alluvial sedimentary rocks in the western United States and the most fertile source for dinosaur bones of the continent.

The Morrison Basin stretched from New Mexico to Alberta and Saskatchewan, being formed when the precursors to the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains started pushing up to the west.

[63] Other dinosaurs known from the Morrison include the theropods Koparion, Stokesosaurus, Ornitholestes, Allosaurus, and Torvosaurus, the sauropods Apatosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Camarasaurus, and Diplodocus, and the ornithischians Camptosaurus, Dryosaurus, Nanosaurus, Gargoyleosaurus, and Stegosaurus.

[44] Other vertebrates that shared this paleoenvironment included ray-finned fishes, frogs, salamanders, turtles like Uluops, sphenodonts, lizards, terrestrial and aquatic crocodylomorphs such as Hoplosuchus, and several species of pterosaurs such as Harpactognathus and Mesadactylus.

According to Mateus and colleagues, the similarity between the Portuguese and North American theropod faunas indicates the presence of a temporary land bridge, allowing for faunal interchange.

[22][23] Malafaia and colleagues, however, argued for a more complex scenario, as other groups, such as sauropods, turtles, and crocodiles, show clearly different species compositions in Portugal and North America.