Chapel of Saint-Jean du Liget

It was probably built around the middle of the 11th century, although this dating is still debated to within a few decades, which maintains the uncertainty as to which monastic order, Benedictine or Carthusian, founded it.

The interior walls of this chapel's rotunda - the only part of the monument to have been preserved, which also had a nave - were covered with Romanesque polychrome frescos, the surviving ones depicting figures of saints and major biblical scenes from the Marian cycle.

It is less than 900 m south-west of the Chartreuse du Liget, of which it was a dependency, and 150 m south-east of the D760 (route from Loches to Montrésor), these distances being expressed as the crow flies.

[1] The chapel is located in the heart of the Loches forest, in a clearing with a former tile factory, also attached to the Carthusian monastery; all these buildings occupy the bottom and slopes of the same Vallon.

[5] However, Albert Philippon, citing an older document in 1934, suggests that Liget may be a deformation of the word lige, indicating a form of dependency[6] between this land and the mother abbey of Villeloin, to which it originally belonged.

It is based on the interpretation of a 14th-century text, but another reading envisages that the dedication actually applies to the Corroirie church;[7] the representation of Saint John in the chapel's decor is far from attested.

The history of the chapel, as presented here, is that towards which the most recent and comprehensive studies tend; it remains a proposal, subject to refinement or contradiction in the light of subsequent work.

[9] Surveys carried out in 1998, which led to the discovery of ceramics from the 11th and 12th centuries, seem to indicate that the site was occupied before the chapel[10] was built; in 1980, Raymond Oursel had already reported the presence of these medieval artifacts on the surface.

[14] The purpose of these land transactions was probably to stabilize new religious[15] communities while seeking to counterbalance the dominance of the Cluniac Benedictines in the region by promoting emerging monastic orders.

After initially proposing, like others,[22] a "low" dating towards the end of the 11th century, historian Christophe Meunier revised his assessment, dating the frescoes to the end of the first half of the 11th century,[23] in agreement with Voichita Munteanu, an art historian who has devoted a thesis to the study of these paintings;[24] in their view, this work is more in keeping with Cluniac pomp than with Carthusian rigor.

[25] In addition, Dom Willibrord Witters mentions that in 1280, a decision of the Carthusian General Chapter ordered the "disappearance" of the Liget paintings.

[8] Ancient documents, and in particular an extract from a 15th century obituary (although the document is imprecise and suffers from chronological[27] errors), suggest that the chapel first served as a church for the Carthusian monastery's upper house (where the fathers devoted to studying and copying books lived), then for the Corroirie (lower house where the brothers responsible for manual and agricultural work lived), until the latter acquired its own church[5] in the 13th century.

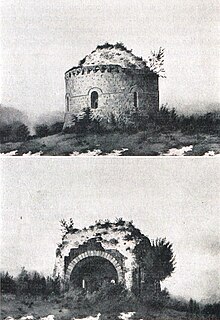

[30] Two watercolors painted in 1850 by Aymar Pierre Verdier show it in a state of disrepair, with the roof missing, revealing the dome of the cupola, the west facade gaping, and the walls overgrown with vegetation.

[47] Although the function of the massive masonry wall framing this door is not yet clear, some historians refute the hypothesis that it could have been part of a sacristy to which it would have given too low a ceiling height.

[55] The interior of the chapel - traces of which are also to be found in the remains of the arch that marked the start of the nave[23] - was entirely decorated with polychrome Romanesque frescos painted when the building was first constructed or shortly afterwards.

Clockwise, from the entrance to the rotunda, we find the Nativity, the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple (this iconographic theme was little used in the Romanesque period, with only three representations in France, including the one at Le Liget),[68] the Descent from the Cross, the Holy Sepulchre and the Dormition of Mary.

[70] Traces of paint on the intrados of the arch marking the start of the nave suggest that other scenes took place here, perhaps the Annunciation and the Visitation, which would be chronologically the first in the cycle, but this hypothesis cannot be verified.

However, unlike the interspersed biblical scenes, they are arranged in a descending "hierarchical" order, starting from the bay opposite the west door, considered "axial".

A manuscript from the Carthusian monastery, preserved in the Tours municipal library but lost in the fire of June 1940, mentions that the abbey possessed relics of most of the saints depicted in the chapel.

[42] Raymond Oursel notes that none of the saints usually honored by the Carthusian monks are represented in the chapel, but that Benedict and Gilles, important figures for the Benedictines,[76] are, and Willibrord Witters makes the same observation.

The proceedings published the following year included a chapter on the Saint-Jean du Liget chapel and its murals, architecture and frescos, written by art historian Marc Thibout.

[73] Voichita Muntenau's 1976 doctoral dissertation at Columbia University, published in 1978 and referred to in numerous subsequent books and articles, is entirely devoted to the study of the chapel's frescos, including proposals on dating, thematics and precise description of the motifs.

Its author, Christophe Meunier, takes stock of the knowledge acquired and the questions still unanswered, and develops the original hypothesis of a construction whose dimensions are an application of the golden ratio.

[90] As part of a doctoral thesis in art history to be defended in 2021, Amaelle Marzais is studying the chapel's frescos from both stylistic and technical points of view, along with the painted decorations of other religious buildings in the Indre-et-Loire region.