Chasmosaurus

[1] In 1898, at Berry Creek, Alberta, Lawrence Morris Lambe of the Geological Survey of Canada made the first discovery of Chasmosaurus remains; holotype NMC 491, a parietal bone that was part of a neck frill.

[2] Although recognizing that his find represented a new species, Lambe thought this could be placed in a previously known short-frilled ceratopsian genus: Monoclonius.

[3] However, in 1913, Charles Hazelius Sternberg and his sons found several complete "M. belli" skulls in the middle Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada.

The name Chasmosaurus is derived from Greek χάσμα, khasma, "opening" or "divide" and refers to the very large parietal fenestrae in the skull frill.

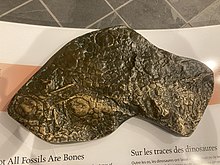

Lambe now also assigned a paratype, specimen NMC 2245 found by the Sternbergs in 1913 and consisting of a largely complete skeleton, including skin impressions.

[6] Since that date, more remains, including skulls, have been found that have been referred to Chasmosaurus, and several additional species have been named within the genus.

In 1933 Barnum Brown named Chasmosaurus kaiseni, honouring Peter Kaisen and based on skull AMNH 5401, differing from C. belli in having very long brow horns.

[8] Charles Mortram Sternberg added Chasmosaurus russelli in 1940, based on specimen NMC 8800 from southwestern Alberta (lower Dinosaur Park Formation).

[16] The most recently described species is Chasmosaurus irvinensis named in 2001,[17] which stems from the uppermost beds of the Dinosaur Park Formation.

All specimens assigned to Mojoceratops were collected from the Dinosaur Park Formation (late Campanian, 76.5–75 ma) of the Belly River Group of Alberta and Saskatchewan, western Canada.

He considered it too poorly preserved for a reliable determination, especially as it belonged to a juvenile individual, and regarded it too as a nomen dubium, rather than as the senior synonym of M.

[10] Following the original assignment of the holotype and other skulls to Mojoceratops, several teams of researchers published work questioning the validity of this new genus.

In 2011, Maidment & Barrett failed to confirm the presence of any supposedly unique features, and argued that Mojoceratops perifania was a synonym of Chasmosaurus russelli.

[20][10] This situation is further complicated since C. russelli may not even belong to the genus Chasmosaurus, sharing features with the contemporaneous derived chasmosaurine Utahceratops.

The skull YPM 2016 and the skull and skeleton AMNH 5402 were noted by Campbell et al. (2016) as differing from other C. belli referred specimens in having more epiparietals, although the authors interpreted them as individual variation, but this was reconsidered when Campbell et al. (2019) interpreted these specimens as an indeterminate Chasmosaurus species closely related to Vagaceratops.

"[20] In 2015, Nicholas Longrich presented a novel theory that posits C. belli and C. russelli are synonymous, while splitting some remains assigned to the latter to a new species, C.

[23] The known differences between the two species mainly pertain to the horn and frill shape, as the referred postcrania of C. russelli are poorly known.

[23] The sides were adorned by six to nine smaller skin ossifications (called episquamosals) or osteoderms, which attached to the squamosal bone.

C. belli possessed a synsacrum, a compound unit composed of sacral, dorsal, and sometimes caudal vertebrae, depending on the specimen.

A certain niche partitioning is suggested by the fact that Chasmosaurus had a longer snout and jaws and might have been more selective about the plants it ate.

In 1933, Lull suggested that C. kaiseni, which bore long brow horns, was in fact the male of C. belli of which the females would have short ones.

The juvenile measured five feet long and was estimated to be three years of age and had similar limb proportions to the adult Chasmosaurus.

Skin impressions were also uncovered beneath the skeleton and evidence from the matrix that it was buried in indicated that the juvenile ceratopsian drowned during a possible river crossing.

[28] Further study of the specimen revealed that juvenile chasmosaurs had a frill that was narrower in the back than that of adults, as well as being proportionately shorter in relation to the skull.