Chemical equation

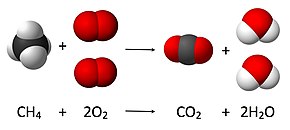

[2] A chemical equation (see an example below) consists of a list of reactants (the starting substances) on the left-hand side, an arrow symbol, and a list of products (substances formed in the chemical reaction) on the right-hand side.

Each substance is specified by its chemical formula, optionally preceded by a number called stoichiometric coefficient.

[a] The coefficient specifies how many entities (e.g. molecules) of that substance are involved in the reaction on a molecular basis.

Alternately, and in general for equations involving complex chemicals, the chemical formulas are read using IUPAC nomenclature, which could verbalise this equation as "two hydrochloric acid molecules and two sodium atoms react to form two formula units of sodium chloride and a hydrogen gas molecule."

Different variants of the arrow symbol are used to denote the type of a reaction:[1] To indicate physical state of a chemical, a symbol in parentheses may be appended to its formula: (s) for a solid, (l) for a liquid, (g) for a gas, and (aq) for an aqueous solution.

For example, the reaction of aqueous hydrochloric acid with solid (metallic) sodium to form aqueous sodium chloride and hydrogen gas would be written like this: That reaction would have different thermodynamic and kinetic properties if gaseous hydrogen chloride were to replace the hydrochloric acid as a reactant: Alternately, an arrow without parentheses is used in some cases to indicate formation of a gas ↑ or precipitate ↓.

The standard notation for chemical equations only permits all reactants on one side, all products on the other, and all stoichiometric coefficients positive.

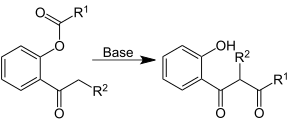

Note that the substances above or below the arrows are not catalysts in this case, because they are consumed or produced in the reaction like ordinary reactants or products.

Thus, each side of the chemical equation must represent the same number of atoms of any particular element (or nuclide, if different isotopes are taken into account).

For example, the reaction corresponding to the standard enthalpy of formation must be written such that one molecule of a single product is formed.

A "preferred" solution is one with whole-number, mostly positive[g] stoichiometric coefficients sj with greatest common divisor equal to one.

First, to unify the reactant and product stoichiometric coefficients sj, let us introduce the quantity called stoichiometric number,[h] which simplifies the linear equations to where J is the total number of reactant and product substances (formulas) in the chemical equation.

For this space to contain nonzero vectors ν, i.e. to have a positive dimension JN, the columns of the composition matrix A must not be linearly independent.

Techniques have been developed[7][8] to quickly calculate a set of JN independent solutions to the balancing problem, which are superior to the inspection and algebraic method[citation needed] in that they are determinative and yield all solutions to the balancing problem.

Its solutions are of the following form, where r is any real number: The choice of r = 1 and a sign-flip of the first two rows yields the preferred solution to the balancing problem: An ionic equation is a chemical equation in which electrolytes are written as dissociated ions.

Ionic equations are used for single and double displacement reactions that occur in aqueous solutions.

Double displacement reactions that feature a carbonate reacting with an acid have the net ionic equation: If every ion is a "spectator ion" then there was no reaction, and the net ionic equation is null.

The zj may be incorporated[7][8] as an additional row in the aij matrix described above, and a properly balanced ionic equation will then also obey: Now Mr. Pfaundler has joined these two phenomena in a single concept by considering the observed limit as the result of two opposing reactions, driving the one in the example cited to the formation of sea salt [i.e., NaCl] and nitric acid, [and] the other to hydrochloric acid and sodium nitrate.

This consideration, which experiment validates, justifies the expression "chemical equilibrium", which is used to characterize the final state of limited reactions.