Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

"[1] This case, part of the Marshall Trilogy, set a precedent for how Native American tribes are treated under federal law and unfolded against the backdrop of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, highlighting the growing tensions over tribal sovereignty.

[2][3] By the late 17th century, the English began trading with the Cherokee, exchanging goods like firearms for alliances in conflicts such as the Tuscarora War.

Despite adopting European-American farming practices and creating a written language and governing system, the Cherokee faced increasing encroachments on their land.

By the early 19th century, white settlers, eager to expand into new lands, pressured the federal government to remove Native American tribes, including the Cherokee Nation.

[8] While early policies under President Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe varied in their commitment to large-scale removal, the Cherokee faced growing external pressure despite their efforts to adopt European-American cultural practices, including farming and governance systems.

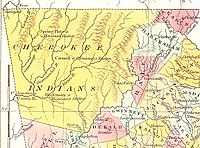

[17] In the fall of 1823, negotiators for the United States met with the Cherokee National Council at the tribe's capital city of New Echota, located in northwest Georgia.

Jackson's administration marked a turning point in federal policy, as he openly supported Georgia's actions and championed the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

Ross found support in Congress from individuals in the National Republican Party, such as senators Henry Clay, Theodore Frelinghuysen, and Daniel Webster, as well as representatives Ambrose Spencer and David (Davy) Crockett.

[20] Congress’s passage of the Indian Removal Act further emboldened Georgia and the Jackson administration, setting the stage for legal and physical confrontations.

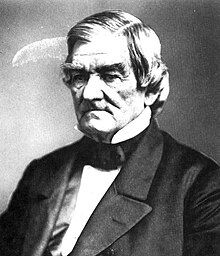

In June 1830, a delegation of Cherokee led by Chief John Ross and represented by William Wirt, a former United States attorney general in the Monroe and Adams administrations, were selected to bring a case before the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Cherokee claimed that Georgia’s actions violated U.S.–Cherokee treaties, the U.S. Constitution, and federal laws regulating interactions with Native tribes.

Georgia countered by arguing that the Cherokee lacked standing as a foreign nation, citing their absence of a constitution and centralized government.

Chief Justice John Marshall emphasized that state laws had no authority within Cherokee territory, as the federal government had recognized Native nations as distinct political communities through treaties.

[23] Over 4,000 Cherokee citizens died during this forced migration to Indian Territory, a tragic event that marked the violent erosion of Native rights and lands.

The Cherokee Nation maintains a sovereign government and oversees services such as healthcare, education, and economic development for its citizens, continuing to uphold its cultural and political legacy despite historical injustices.

Tribes are considered "domestic dependent nations," retaining inherent rights to self-governance, control over their lands, and the ability to regulate their members and economic activities.

Modern Native advocacy often draws on Worcester v. Georgia to challenge federal and state policies that infringe on tribal sovereignty.

Recent cases, such as McGirt v. Oklahoma (2020), reaffirmed the principle that treaties with Native nations must be upheld, reinforcing tribal jurisdiction over their historic lands.