Israelites

Most modern scholars agree that the Torah does not provide an authentic account of the Israelites' origins, and instead view it as constituting their national myth.

[31][32][33] The folk etymology given in the text derives Israel from yisra, "to prevail over" or "to struggle with", and El, a Canaanite-Mesopotamian creator god that is tenuously identified with Yahweh.

"Jew" (or "Judean") was another popular ethnonym but it might refer to a geographically restricted sub-group or to the inhabitants of the southern kingdom of Judah.

[51][52] In addition, works such as Ezra-Nehemiah pioneered the idea of an "impermeable" distinction between Israel and gentiles, on a genealogical basis.

[54] In Judaism, "Israelite", broadly speaking, refers to a lay member of the Jewish ethnoreligious group, as opposed to the priestly orders of Kohanim and Levites.

[55][56][full citation needed][57] The history of the Israelite people can be divided into these categories, according to the Hebrew Bible:[58] Efforts to confirm the biblical ethnogenesis of Israel through archaeology have largely been abandoned as unproductive.

[82][83][84] Their culture was monolatristic, with a primary focus on Yahweh (or El) worship,[35] but after the Babylonian exile, it became monotheistic, with partial influence from Zoroastrianism.

[85][86] Gary Rendsburg argues that some archaic biblical traditions and other circumstantial evidence point to the Israelites emerging from the Shasu and other seminomadic peoples from the desert regions south of the Levant, later settling in the highlands of Canaan.

Some believe they descended from raiding groups, itinerant nomads such as Habiru and Shasu or impoverished Canaanites, who were forced to leave wealthy urban areas and live in the highlands.

[93][95][page needed] Besides their focus on Yahweh worship, Israelite cultural markers were defined by body, food, and time, including male circumcision, avoidance of pork consumption and marking time based on the Exodus, the reigns of Israelite kings, and Sabbath observance.

[100] That said, Israelites used genealogy to engage in narcissism of small differences but also, self-criticism since their ancestors included morally questionable characters such as Jacob.

[98] In terms of appearance, rabbis described the Biblical Jews as being "midway between black and white" and having the "color of the boxwood tree".

[105] Based on biblical literature, it is implied that the Israelites distinguished themselves from peoples like the Babylonians and Egyptians by not having long beards and chin tufts.

[106] In the 12th century BCE, many Israelite settlements appeared in the central hill country of Canaan, which was formerly an open terrain.

[107] These settlements were built by inhabitants of the "general Southland" (i.e. modern Sinai and the southern parts of Israel and Jordan), who abandoned their pastoral-nomadic ways.

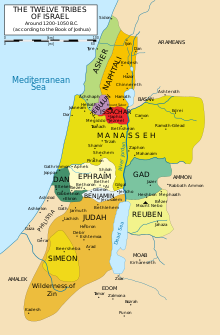

Canaanites who lived outside the central hill country were tenuously identified as Danites, Asherites, Zebulunites, Issacharites, Naphtalites and Gadites.

Possible allusions to this historical reality in the Hebrew Bible include the aforementioned tribes, except for Issachar and Zebulun, descending from Bilhah and Zilpah, who were viewed as "secondary additions" to Israel.

[34][35] Himbaza et al. (2012) states that Israelite households were typically ill-equipped to handle conflicts between family members, which may explain the harsh sexual taboos enforced against acts like incest, homosexuality, polygamy etc.

Whilst the death penalty was legislated for these 'secret crimes', they functioned as a warning, where offenders would confess out of fear and make appropriate reparations.

The debate has not been resolved, but recent archaeological discoveries by Eilat Mazar and Yosef Garfinkel show some support for the existence of the United Monarchy.

[119] This theory has been rejected by other scholars, who argue that the archaeological evidence seems to indicate that Judah was an independent socio-political entity for most of the 9th century BCE.

[120] Avraham Faust argues that there was continued adherence to the 'ethos of egalitarianism and simplicity' in the Iron Age II (10th-6th century BCE).

For example, there is minimal evidence of temples and complex tomb burials, despite Israel and Judah being more densely populated than the Late Bronze Age.

[131][132][133][134] Towards the end of the same century, the Neo-Babylonian Empire emerged victorious over the Assyrians, leading to Judah's subjugation as a vassal state.

In the early 6th century BC, a series of revolts in Judah prompted the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II to lay siege to and destroy Jerusalem along with the First Temple, marking the kingdom's demise.

[139][140] The returnees showed a "heightened sense" of their ethnic identity and shunned exogamy, which was treated as a "permissive reality" in Babylon.

The Maccabean Revolt against Seleucid rule ushered in a period of nominal independence for the Jewish people under the Hasmonean dynasty (140–37 BCE).

[149][150][151][152] Several scholars, such as Scot McKnight and Martin Goodman, reject this view while holding that conversions occasionally occurred.

During this period, the main areas of Jewish settlement in the Land of Israel were Judea, Galilee and Perea, while the Samaritans had their demographic center in Samaria.

The analysis examined First Temple-era skeletal remains excavated in Abu Ghosh, and showed one male individual belonging to the J2 Y-DNA haplogroup, a set of closely-related DNA sequences thought to have originated in the Caucasus or Eastern Anatolia, as well as the T1a and H87 mitochondrial DNA haplogroups, the former of which has also been detected among Canaanites, and the latter in Basques, Tunisian Arabs, and Iraqis, suggesting a Mediterranean, Near Eastern, or perhaps Arabian origin.