Sources and parallels of the Exodus

[4] Nevertheless, it is also commonly argued that some historical event may have inspired these traditions, even if Moses and the Exodus narrative belong to the collective cultural memory rather than history.

"[6] Egyptologist Jan Assmann suggests that the Exodus narrative combines, among other things, the expulsion of the Hyksos, the religious revolution of Akhenaten, the experiences of the Habiru (gangs of antisocial elements found throughout the ancient Near East), and the large-scale migrations of the Sea Peoples into "a coherent story that is fictional as to its composition but historical as to some of its components.

[9] In contrast to the absence of evidence for the Egyptian captivity and wilderness wanderings, there are ample signs of Israel's evolution within Canaan from native Canaanite roots.

[14] A century of research by archaeologists and Egyptologists has found no evidence which can be directly related to the Exodus captivity and the escape and travels through the wilderness.

[17] According to Exodus 12:37–38, the Israelites numbered "about six hundred thousand men on foot, besides women and children", plus the Erev Rav ("mixed multitude") and their livestock.

[33][34] In any case, Canaan at this time was part of the Egyptian empire, so that the Israelites would in effect be escaping from Egypt to Egypt,[35] and its cities do not show destruction layers consistent with the Book of Joshua's account of the occupation of the land (Jericho was "small and poor, almost insignificant, and unfortified (and) [t]here was also no sign of a destruction" (Finkelstein and Silberman, 2002).

[36] William F. Albright, the leading biblical archaeologist of the mid-20th century, proposed a date of around 1250–1200 BCE, but his so-called "Israelite" markers (four-roomed houses, collar-rimmed jars, etc.)

A few of the names at the start of the itinerary, including Ra'amses, Pithom and Succoth, are reasonably well identified with archaeological sites on the eastern edge of the Nile Delta,[26] as is Kadesh-Barnea, where the Israelites spend 38 years after turning back from Canaan; other than these, very little is certain.

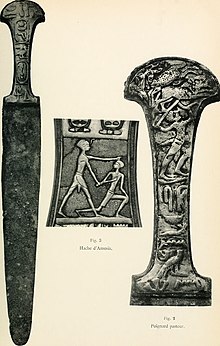

[42][43] It has been claimed that new revolutionary methods of warfare ensured for the Hyksos their ascendancy, in their influx into the new emporia being established in Egypt's delta and at Thebes in support of the Red Sea trade.

Eventually, Seqenenre Tao, Kamose and Ahmose I waged war against the Hyksos and expelled Khamudi, their last king, from Egypt c. 1550 BCE.

[41] Archaeologists Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman argued that the exodus narrative perhaps evolved from vague memories of the Hyksos expulsion, spun to encourage resistance to the 7th century domination of Judah by Egypt.

[53] Jan Assmann said the biblical narrative is more like a counterhistory: "It turns kings into slaves; an expulsion into a ban on emigration; a descent from the Egyptian throne to insignificance into an ascent from oppression to freedom as god's chosen people.

[59] Apocalyptic rainstorms, which devastated much of Egypt, and were described on the Tempest Stele of Ahmose I, pharaoh of the Hyksos expulsion, have been attributed to short-term climatic changes caused by the Theran eruption.

[67] Basing his arguments on a belief that the Exodus story was historical, Freud argued that Moses had been an Atenist priest forced to leave Egypt with his followers after Akhenaten's death.

[6] One text of this period which has been connected to the Exodus narrative is Papyrus Leiden 348, which refers to construction works at Pi-Ramesses (Biblical Rameses).

One section of this papyrus contains the order “Issue grain to the men of the army and (to) the ʿApiru who are drawing stone for the great pylon of the [...] of Ramesses.”[71] Many scholars have suggested a linguistic connection between the terms 'Apiru (or Habiru) and Hebrews, so this text may provide a possible (yet uncertain) reference to some proto-Israelites doing construction work at Pi-Ramesses during this period.

[74] Bitetak and Rendsburg hold that this parallel "suggests that the Israelites were using a route well traveled by fugitive slaves, somewhat akin to the “underground railroad” of American history".

[78][page needed] Several ancient non-biblical sources seem to parallel the biblical Exodus narrative or the events which occurred at the end of the eighteenth dynasty when the new religion of Akhenaten was denounced and his capital city of Amarna was abandoned.

[79] For example, Hecataeus of Abdera (c. 320 BCE) tells how the Egyptians blamed a plague on foreigners and expelled them from the country, whereupon Moses, their leader, took them to Canaan.

[80] Manetho tells how 80,000 lepers and other "impure people", led by a priest named Osarseph, join forces with the former Hyksos, now living in Jerusalem, to take over Egypt.

A proposal by Egyptologist Jan Assmann[85] suggests that the story has no single origin but rather combines numerous historical experiences, notably the Amarna and Hyksos periods, into a folk memory.