Varieties of Chinese

These groups are neither clades nor individual languages defined by mutual intelligibility, but reflect common phonological developments from Middle Chinese.

Standard Chinese takes its phonology from the Beijing dialect, with vocabulary from the Mandarin group and grammar based on literature in the modern written vernacular.

[7] During periods of political unity there was a tendency for states to promote the use of a standard language across the territory they controlled, in order to facilitate communication between people from different regions.

Although the Zhou royal domain was no longer politically powerful, its speech still represented a model for communication across China.

[10] This standard is known as Middle Chinese, and is believed to be a diasystem, based on a compromise between the reading traditions of the northern and southern capitals.

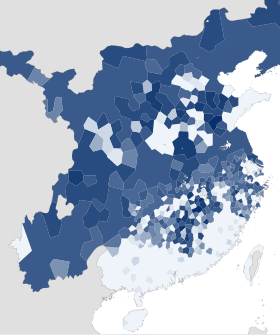

[11] The North China Plain provided few barriers to migration, which resulted in relative linguistic homogeneity over a wide area.

Contrastingly, the mountains and rivers of southern China contain all six of the other major Chinese dialect groups, with each in turn featuring great internal diversity, particularly in Fujian.

As a practical measure, officials of the Ming and Qing dynasties carried out the administration of the empire using a common language based on Mandarin varieties, known as Guānhuà (官話/官话 'officer speech').

Medieval Latin remained the standard for scholarly and administrative writing in Western Europe for centuries, influencing local varieties much like Literary Chinese did in China.

In both cases, local forms of speech diverged from both the literary standard and each other, producing dialect continua with mutually unintelligible varieties separated by long distances.

[26] These varieties form a dialect continuum, in which differences in speech generally become more pronounced as distances increase, although there are also some sharp boundaries.

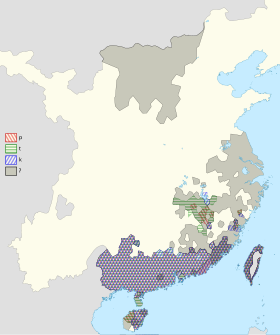

[31] The conventionally accepted set of seven dialect groups first appeared in the second edition (1980) of Yuan Jiahua's dialectology handbook:[32][33] The Language Atlas of China (1987) follows a classification of Li Rong, distinguishing three further groups:[46][47] Some varieties remain unclassified, including the Danzhou dialect (northwestern Hainan), Mai (southern Hainan), Waxiang (northwestern Hunan), Xiangnan Tuhua (southern Hunan), Shaozhou Tuhua (northern Guangdong), and the forms of Chinese spoken by the She people (She Chinese) and the Miao people.

Some scholars have suggested that it represents a very early branching from Chinese, while others argue that it is a more distantly related Sino-Tibetan language overlaid with two millennia of loans.

[57][58][59] Jerry Norman classified the traditional seven dialect groups into three zones: Northern (Mandarin), Central (Wu, Gan, and Xiang) and Southern (Hakka, Yue, and Min).

[66] The long history of migration of peoples and interaction between speakers of different dialects makes it difficult to apply the tree model to Chinese.

In a few cases, listeners understood fewer than 70% of words spoken by speakers from the same province, indicating significant differences between urban and rural varieties.

[74] The scores supported a primary division between northern groups (Mandarin and Jin) and all others, with Min as an identifiable branch.

[114] All varieties of Chinese, like neighbouring languages in the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, have phonemic tones.

Furthermore, final stop consonants disappeared in most Mandarin dialects, and such syllables were distributed amongst the four remaining tones in a manner that is only partially predictable.

[137] Chinese varieties generally lack inflectional morphology and instead express grammatical categories using analytic means such as particles and prepositions.

[139] As in languages of the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, Chinese varieties require an intervening classifier when a noun is preceded by a demonstrative or numeral.

[158] A two-way distinction between proximal and distal is most common, but some varieties have a single neutral demonstrative, while others distinguish three or more on the basis of distance, visibility or other properties.

[167] All other varieties use a form cognate with shì 是, which was a demonstrative in Classical Chinese but began to be used as a copula from the Han period.

[181] Northern and Central varieties tend to use a word from the first family, cognate with Beijing bù 不, as the ordinary negator.

Parents will generally speak to their children in the local variety, and the relationship between dialect and Mandarin appears to be mostly stable, even a diglossia.

For instance, on the Taipei metro when nearing the next station, a passenger will hear these languages in the following order: Mandarin, English, Hokkien, Hakka, sometimes followed by Japanese and Korean.

Within mainland China, there has been a persistent Promotion of Putonghua drive; for instance, the education system is entirely Mandarin-medium from the second year onward.

In Hong Kong, written Cantonese is not used in formal documents, and within the PRC a character set closer to Mandarin tends to be used.

[198] They also aggravated social divisions, as Mandarin speakers found it difficult to find jobs in private companies but were favored for government positions.

[204][205] According to the government, for the bilingual policy to be effective, Mandarin should be spoken at home and should serve as the lingua franca among Chinese Singaporeans.