Christian monasticism

Christian monasticism has varied greatly in its external forms, but, broadly speaking, it has two main types: (a) the eremitical or secluded, (b) the cenobitical or city life.

[15][failed verification] Early Christian ascetics have left no confirmed archaeological traces and only hints in the written record[citation needed].

There were also individual ascetics, known as the "devout", who usually lived not in the deserts but on the edge of inhabited places, still remaining in the world but practicing asceticism and striving for union with God.

In ante-Nicene asceticism, a man would lead a single life, practice long and frequent fasts, abstain from meat and wine, and support himself, if he were able, by some small handicraft, keeping of what he earned only so much as was absolutely necessary for his own sustenance, and giving the rest to the poor.

[9] At Tabenna in Upper Egypt, sometime around 323 AD, Pachomius decided to mold his disciples into a more organized community in which the monks lived in individual huts or rooms (cellula in Latin,) but worked, ate, and worshipped in shared space.

The intention was to bring together individual ascetics who, although pious, did not, like Saint Anthony, have the physical ability or skills to live a solitary existence in the desert.

[26] Orthodox monasticism does not have religious orders as in the West,[27] therefore there are no formal Monastic Rules (Regulae); rather, each monk and nun is encouraged to read all of the Holy Fathers and emulate their virtues.

Even before Saint Anthony the Great (the "father of monasticism") went out into the desert, there were Christians who devoted their lives to ascetic discipline and striving to lead an evangelical life (i.e., in accordance with the teachings of the Gospel).

Saint Basil's ascetical writings set forth standards for well-disciplined community life and offered lessons in what became the ideal monastic virtue: humility.

[29] Monastic centers thrive to this day in Bulgaria, Ethiopia, Georgia, Greece, North Macedonia, Russia, Romania, Serbia, the Holy Land, and elsewhere.

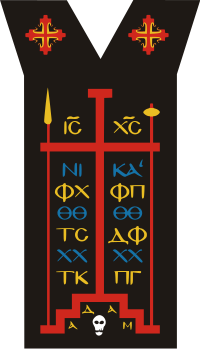

In the early days of monasticism, there was only one level—the Great Schema—and even Saint Theodore the Studite argued against the establishment of intermediate grades, but nonetheless the consensus of the church has favored the development of three distinct levels.

After a period of about three years, the Hegumen may at his discretion tonsure the novice as a Rassophore monk, giving him the outer garment called the Rassa (Greek: Rason).

The Paramand is so-called because it is worn under the Mantle (Greek: Mandyas; Church Slavonic: Mantya), which is a long cape which completely covers the monk from neck to foot.

The publication of the "Vita Antonii" some years later and its translation into Latin spread the knowledge of Egyptian monachism widely and many were found in Italy to imitate the example thus set forth.

[5] Honoratus of Marseilles was a wealthy Gallo-Roman aristocrat, who after a pilgrimage to Egypt, founded the Monastery of Lérins in 410, on an island lying off the modern city of Cannes.

[32] According to James F. Kenney, every important church was a monastic establishment, with a small walled village of monks and nuns living under ecclesiastical discipline, and ministering to the people of the surrounding area.

Samson founded a monastery in an abandoned Roman fort near the river Severn and lived for a time the life of a hermit in a nearby cave before going to Brittany.

Subjects taught included Latin, Greek, Hebrew, grammar, rhetoric, poetry, arithmetic, chronology, the Holy Places, hymns, sermons, natural science, history and especially the interpretation of Sacred Scripture.

"Spouses of God") were members of ascetic Christian monastic and eremitical communities of Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England in the Middle Ages.

While the Celtic monasteries had a stronger connection to the semi-eremitical tradition of Egypt via Lérins and Tours, Benedict and his followers were more influenced by the cenobitism of St Pachomius and Basil the Great.

Early Benedictine monasteries were relatively small and consisted of an oratory, refectory, dormitory, scriptorium, guest accommodation, and out-buildings, a group of often quite separate rooms more reminiscent of a decent-sized Roman villa than a large medieval abbey.

One monk wrote about how he did not mind the bad weather one evening because it kept the Vikings from coming: "Bitter is the wind tonight, it tosses the ocean's white hair, I need not fear—as on a night of calm sea—the fierce raiders from Lochlann.

Jus novum (c. 1140-1563) Jus novissimum (c. 1563-1918) Jus codicis (1918-present) Other Sacraments Sacramentals Sacred places Sacred times Supra-diocesan/eparchal structures Particular churches Juridic persons Philosophy, theology, and fundamental theory of Catholic canon law Clerics Office Juridic and physical persons Associations of the faithful Pars dynamica (trial procedure) Canonization Election of the Roman Pontiff Academic degrees Journals and Professional Societies Faculties of canon law Canonists Institute of consecrated life Society of apostolic life After the foundation of the Lutheran Churches, some monasteries in Lutheran lands (such as Amelungsborn Abbey near Negenborn and Loccum Abbey in Rehburg-Loccum) and convents (such as Ebstorf Abbey near the town of Uelzen and Bursfelde Abbey in Bursfelde) adopted the Lutheran Christian faith.

In 1958, men joined Father Arthur Kreinheder in observing the monastic life and offices of prayer and "The Congregation of the Servants of Christ" was established at St. Augustine's House[60] in Oxford, Michigan.

[64] In Lutheran Sweden, religious life for women had been established by 1954, when Sister Marianne Nordström made her profession through contacts with The Order of the Holy Paraclete and Mother Margaret Cope (1886–1961) at St Hilda's Priory, Whitby, Yorkshire.

[65] In England, John Wycliffe organized the Lollard Preacher Order (the "Poor Priests") to promote his views, many of which resounded with those held by the later Protestant Reformers.

From the 1840s and throughout the following one hundred years, religious orders for both men and women proliferated in the UK and the United States, as well as in various countries of Africa, Asia, Canada, India and the Pacific.

[67] The Hutterites and Bruderhof, for example, live in intentional communities with their big houses having "ground floors for common work, meals and worship, the two-storey attics with small rooms, like monastic cells, for married couples".

In 2005, archeologists uncovered waste at Soutra Aisle which helped scientists figure out how people in the Middle Ages treated certain diseases, such as scurvy; because of the vitamin C in watercress, patients would eat it to stop their teeth from falling out.

Monasteries also provided refuge to those like Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor who retired to Yuste in his late years, and his son Philip II of Spain.