Christianity in the 11th century

Though this event, in and of itself, was relatively insignificant (and the authority of the legates in their actions was dubious) it ultimately marked the end of any pretense of a union between the eastern and western branches of the Church.

It began as a dispute in the 11th century between the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV, and Pope Gregory VII concerning who would appoint bishops (investiture).

The English dispute was resolved by the Concordat of London in 1107, where the king renounced his claim to invest bishops but continued to require an oath of fealty from them upon their election.

This was a partial model for the Concordat of Worms (Pactum Calixtinum), which resolved the imperial investiture controversy with a compromise that allowed secular authorities some measure of control but granted the selection of bishops to their cathedral canons.

The Battle of Kleidion was a disaster for the Bulgarians and the Byzantine army captured 15,000 prisoners; 99 out of every 100 was blinded and the 100th was spared one eye to guide the rest back to their homes.

However, while the archbishopric was completely independent in any other aspect, its primate was selected by the emperor from a list of three candidates submitted by the local church synod.

To a large extent the archbishopric preserved its national character, upheld the Slavonic liturgy, and continued its contribution to the development of Bulgarian literature.

With the division and decline of the Carolingian Empire, notable theological activity was preserved in some of the Cathedral schools that had begun to rise to prominence under it – for instance at Auxerre in the 9th century or Chartres in the 11th.

Notable authors include: One of the major developments in monasticism during the 11th century was the height of the Cluniac reforms, which centred upon Cluny Abbey in Burgundy, which controlled a large centralised order with over two hundred monasteries throughout Western Christendom.

Cluny championed a revived Papacy during this century and encouraged stricter monastic discipline with a return to the principles of the Benedictine Rule.

Towards the end of the 12th century, the wealth and power of Cluny was criticised by many monastics in the Church, especially those that broke from the Cluniac order to form the Cistercians, who devoted themselves with much greater rigor to manual labour and severe austerity.

Migrations of peoples, although not strictly part of the 'Migration Age', continued beyond 1000, marked by Viking, Magyar, Turkic and Mongol invasions, also had significant effects, especially in eastern Europe.

During the later centuries following the Fall of Rome, as the Roman Church gradually split between the dioceses loyal to the Patriarch of Rome in the West and those loyal to the other Patriarchs in the East, most of the Germanic peoples (excepting the Crimean Goths and a few other eastern groups) gradually became strongly allied with the Western Church, particularly as a result of the reign of Charlemagne.

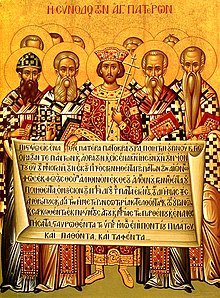

[4] There were doctrinal issues like the filioque clause and the authority of the Pope involved in the split, but these were exacerbated by cultural and linguistic differences between Latins and Greeks.

Soon after the fall of the Western Empire, the number of individuals who spoke both Latin and Greek began to dwindle, and communication between East and West grew much more difficult.

In the Orthodox view, the Bishop of Rome (i.e. the Pope) would have universal primacy in a reunited Christendom, as primus inter pares without power of jurisdiction.

It was suspected by the Patriarch that the bull of excommunication, placed on the altar of Hagia Sophia, had been tampered with by Argyros, the commander of Southern Italy, who had a drawn-out controversy with Michael I Cerularius.

Humbert, Frederick of Lorraine, and Peter, Archbishop of Amalfi arrived in April 1054 and were met with a hostile reception; they stormed out of the palace, leaving the papal response with Michael, who in turn was even more angered by their actions.

[12] In response to Michael's refusal to address the issues at hand, the legatine mission took the extreme measure of entering the church of the Hagia Sophia during the divine liturgy and placing a Bull of Excommunication (1054) on the altar.

In the bull of excommunication issued against Patriarch Michael by the papal legates, one of the reasons cited was the Eastern Church's deletion of the "Filioque" from the original Nicene Creed.

In 1009, when the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah destroyed the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, but in 1039 his successor was paid a large sum by the Byzantine Empire to rebuild it.

In 1063, Pope Alexander II had given his blessing to Iberian Christians in their wars against the Muslims, granting both a papal standard, the vexillum sancti Petri, and an indulgence to those killed in battle.

This long history of losing territories to a religious enemy created a powerful motive to respond to Byzantine Emperor Alexius I's call for holy war to defend Christendom and to recapture the lost lands starting with Jerusalem.

Saint Augustine of Hippo had justified the use of force in the service of Christ in The City of God, and a Christian just war although this might enhance the Papacy's standing in Europe, stem violence amongst the western nobility as the "Peace of God" movement had failed and provide leverage the claims of supremacy over the Patriarch of Constantinople, which had resulted in the Great Schism of 1054.

For Gregory's successor, Pope Urban II, a crusade would serve to reunite Christendom, bolster the Papacy, and perhaps bring the East under his control.

In March 1095 at the Council of Piacenza, ambassadors sent by Byzantine Emperor Alexius I called for help with defending his empire against the Seljuk Turks.

Later that year, at Clermont, Pope Urban II called upon all Christians to join a war against the Turks, promising those who died in the endeavor would receive immediate remission of their sins.

[17] One historian has written that the "isolation, alienation and fear"[18] felt by the Franks so far from home helps to explain the atrocities they committed, including the cannibalism which was recorded after the Siege of Maarat in 1098.

When the Franks were defeated the people of Tyre did not surrender the city, but Zahir al-Din simply said "What I have done I have done only for the sake of God and the Muslims, nor out of desire for wealth and kingdom.