Christianization of the Roman Empire as diffusion of innovation

In the empire's first three centuries, Roman society moved away from its established city based polytheism to adopt the religious innovation of monotheistic Christianity.

[13] Societal change can then be seen as a kind of emergence – the collective behavior that results from individuals as parts of a system doing together what they would not do alone – as Christianity was 'self-organized', distributed away from any central authority, and was based on common causes.

[14] When groups of people with different ways of life come into contact with each other, interact, and exchange ideas and practices, "cultural diffusion" takes place.

[21] Archaeologist Anna Collar argues that even though "the philosophical argument for one god was well known amongst the intellectual elite, ... monotheism can be called a religious innovation within the milieu of Imperial polytheism.

Gibbon attributed it to Constantine whom he saw as driven by "boundless ambition" and a desire for personal glory to impose Christianity on the rest of the empire – from the top down – in a cynical, political move.

It embodies a negative view, and it leads to the idea of a linear spread where the new cult infected each place it passed through, and this was not the case in Roman Empire.

[52] Pagan society had weak traditions of mutual aid, whereas the Christian community had norms that created “a miniature welfare state in an empire which for the most part lacked social services”.

[31] According to Boyd and Richardson, this created a kind of welfare state within an empire which for the most part had no such thing, and this gave Romans the belief that the early Christian community offered a better quality of life.

[65] The wealthy supported their own who had fallen on hard times, first and foremost, and philanthropy was likely to be a display of personal wealth rather than concern for the needy.

[66] Prior to Christianity, the wealthy elite of Rome mostly donated to civic programs designed to elevate their social status, though personal acts of kindness to the poor were not unheard of.

[70] In his Homilies on St.John, John Chrysostom writes that "It is impossible, though we perform ten thousand other good deeds, to enter the portals of the kingdom without almsgiving".

[73] According to early Christian historian Chris L. de Wet, slavery suffered a complete systemic collapse in the fifth century due to the lack of supply and demand.

[75] However, there is evidence indicating Christian discourse against slavery was oft repeated and shaped late ancient feelings, tastes, and opinions concerning it.

[81] Paul's understanding of the paradox of a powerful Christ who died as a powerless human led to the creation of a new order unprecedented in classical society.

[123] Syrian church historian Bar Hebraeus puts the total number of Jews throughout the entire Roman empire, at the time of the emperor Claudius, at 6,944,000.

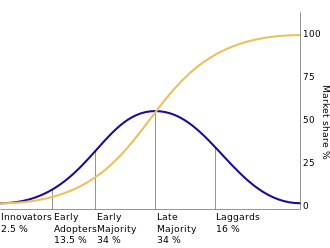

[127] In the empire, this involved becoming part of an established community of adopters who would "instruct, admonish, cajole, remind, rebuke, reform, and argue" for the change, says Meeks.

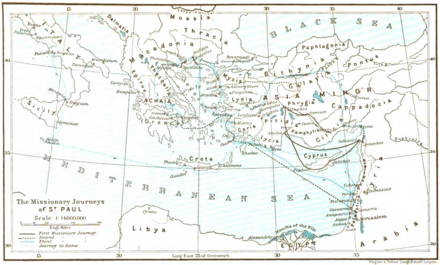

[149] Indian historian K. S. Mathew writes that it has been proven "indubitably" that after Thomas left Mesopotamia, he began to preach the gospel in India in the year 52.

[141] According to social anthropologist and Biblical scholar Wayne A. Meeks, the absence of source material means it is not possible to write an empirical sociology of early Christianity.

[155] However, the Pauline epistles provide some of the earliest documentary evidence showing women, connected to Paul, among the early adopters of the religious innovation in the Roman Empire.

[162] There are a number of signs that women did enjoy a functional equality in Christianity that would have been unusual in the larger Roman society and "quite astonishing" in Second Temple Judaism.

[167] This is evident in the sanctions and labels found in pagan writings such as The True Word by Celsus, a treatise against Christianity and the women he held responsible for it.

[168] Power resided with the male authority figure, and he had the right to label any uncooperative female in his household as insane or possessed, to exile her from her home, and condemn her to prostitution.

[169] Professor of religious studies Ross Kraemer theorizes that "Against such vehement opposition, the language of the ascetic forms of Christianity must have provided a strong set of validating mechanisms", attracting large numbers of women.

[186] Classical scholar Kyle Harper writes that Christianity in the third and fourth centuries drove profound social and cultural change, and this is demonstrated in the creation of a new relationship between sexual morality and society.

[190] Paul the Apostle and his followers taught that the ethical obligation for sexual self-control was to God, and it was placed on each individual, male and female, slave and free, equally, in all communities, regardless of status.

[191] Modular scale free networks such as the early Christian churches, are "robust," which means "they grow without central direction, but also survive most attempts to wipe them out.

[200] The result of persecution, according to second century Justin Martyr, was that: "... the more such things happen, the more do others and in larger numbers become faithful, and worshippers of God through the name of Jesus".

[224] Stark explains that conversion moves along social networks formed by personal attachments, but Salzman asserts that class ties were even more important to this group.

[229] This produced a "vigorous flowering of a public culture that Christians and non-Christians alike could share" – without the practice of sacrifice – which meant the two religious traditions co-existed, and, for the most part, tolerated each other throughout the period.

[230][231][232] By the late fourth and early fifth centuries, polytheism had evolved and adapted many aspects of the new religion, while the structure and ideals of both the Church and the Empire had also been transformed.