Cimmeria (continent)

It consisted of parts of present-day Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Tibet, China, Myanmar, Thailand, and Malaysia.

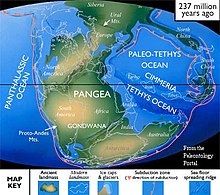

[12] German geophysicist Alfred Wegener, in contrast, developed a concept of a single, global continent – the supercontinent Pangea – which, in his view, left no room for an equatorial ocean.

[14] Stöcklin also noted that his proposal resembled the old concept of the world in which there were two continents, Angaraland in the north and Gondwana in the south, separated by an elongated ocean, the Tethys.

These two orogenic systems are thus associated with two major periods of ocean closure: the earlier, northern, and much larger Cimmerides, and the later, southern, and smaller Alpides.

The Alpine Tethys, the western domain in this scheme, separated south-western Europe from north-western Africa and was connected to the Central Atlantic.

Carboniferous to Permian ophiolites along suture zones in Tibet and north-eastern Iran indicate that the active margin of Paleo-Tethys was located here.

Slab roll-back in the Paleo-Tethys opened a series of back-arc basins along the Eurasian margin and resulted in the collapse of the Variscan cordillera.

[24] In the late Cretaceous northwards intra-oceanic subduction within the Neotethys gave way to the obduction of ophiolitic nappes over the Arabian platform from Turkey to Oman region.

In the Early Jurassic this magmatism had produced a slab pull force which contributed to the break-up of Pangea and the initial opening of the Atlantic.

During the Late Jurassic-Early Cretaceous the subduction of the Neo-Tethys mid-ocean ridge contributed to the break-up of Gondwana, including the detachment of the Argo-Burma terrane from Australia.

[26] The Greater and Lesser Caucasus have a complicated geological history involving the accretion of a series of terranes and microcontinents from the Late Precambrian to the Jurassic within the Tethyan framework.

[27] In the Caucasus region remnants of the Paleo-Tethys suture can be found in the Dzirula Massif which outcrops Early Jurassic sequences in central Georgia.

It consists of Early Cambrian oceanic rocks and the possible remnants of a magmatic arc; their geometry suggests that suturing was followed by strike-slip faulting.

[28] The easternmost part of Cimmeria, the Sibumasu terrane, remained attached to north-western Australia until 295–290 Ma when it began to drift northward, as supported by paleomagnetic and biogeographic data.

[30] Paleomagnetic data indicate South China and Indochina moved from near equator to 20°N from the early Permian to late Triassic.

This is also supported by geological evidence: 200–230 Ma granite in Lincang, near the Changning–Menglian suture, indicate a continent–continent collision occurred there in the late Triassic; pelagic sediments in the Changning–Menglian–Inthanon ophiolite belt (between Sibumasu and Indochina) ranges in age from middle Devonian to middle Triassic, while, in the Inthanon suture, in contrast, middle to late Triassic rocks are non-pelagic with radiolarian cherts and turbidic clastics indicating the two blocks had at least approached each other by that time; volcanic sequences from the Lancangjiang igneous zone indicate a post-collisional setting had developed before the eruptions there around 210 Ma; and, the Sibumasu fauna developed from a non-marine peri-Gondwanan assemblage in the early Permian, to an endemic Sibumasu fauna in the middle Permian, and to an Equatorial–Cathaysian in the late Permian.

Glacial deposits and paleomagnetic data indicate that Qiangtang and Shan Thai–Malaya were still located far south adjacent to Gondwana during the Carboniferous.

The present remains of Cimmeria, as a result of the massive uplifting of its continental crust, are unusually rich in a number of rare chalcophile elements.

Apart from the Altiplano in Bolivia, almost all the world's deposits of antimony as stibnite are found in Cimmeria, with the major mines being in Turkey, Yunnan and Thailand.