Circadian rhythm

[4] The earliest recorded account of a circadian process is credited to Theophrastus, dating from the 4th century BC, probably provided to him by report of Androsthenes, a ship's captain serving under Alexander the Great.

[7] In 1729, French scientist Jean-Jacques d'Ortous de Mairan conducted the first experiment designed to distinguish an endogenous clock from responses to daily stimuli.

[13][14] In 1954, an important experiment reported by Colin Pittendrigh demonstrated that eclosion (the process of pupa turning into adult) in Drosophila pseudoobscura was a circadian behaviour.

[16] According to Halberg's original definition: The term "circadian" was derived from circa (about) and dies (day); it may serve to imply that certain physiologic periods are close to 24 hours, if not exactly that length.

Note: term describes rhythms with an about 24-h cycle length, whether they are frequency-synchronized with (acceptable) or are desynchronized or free-running from the local environmental time scale, with periods of slightly yet consistently different from 24-h.[19]Ron Konopka and Seymour Benzer identified the first clock mutation in Drosophila in 1971, naming the gene "period" (per) gene, the first discovered genetic determinant of behavioral rhythmicity.

[21][22] At the same time, Michael W. Young's team reported similar effects of per, and that the gene covers 7.1-kilobase (kb) interval on the X chromosome and encodes a 4.5-kb poly(A)+ RNA.

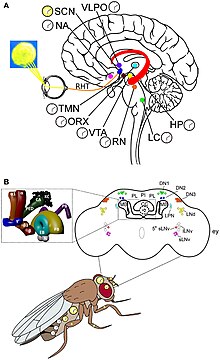

[23][24] They went on to discover the key genes and neurones in Drosophila circadian system, for which Hall, Rosbash and Young received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2017.

[28][29] The first human clock mutation was identified in an extended Utah family by Chris Jones, and genetically characterized by Ying-Hui Fu and Louis Ptacek.

Previous hypotheses emphasized that photosensitive proteins and circadian rhythms may have originated together in the earliest cells, with the purpose of protecting replicating DNA from high levels of damaging ultraviolet radiation during the daytime.

[37] Recent studies instead highlight the importance of co-evolution of redox proteins with circadian oscillators in all three domains of life following the Great Oxidation Event approximately 2.3 billion years ago.

Recent research has demonstrated that the circadian clock of Synechococcus elongatus can be reconstituted in vitro with just the three proteins (KaiA, KaiB, KaiC)[38] of their central oscillator.

[45] In mice, deletion of the Rev-ErbA alpha clock gene can result in diet-induced obesity and changes the balance between glucose and lipid utilization, predisposing to diabetes.

[page needed][50] Free-running organisms that normally have one or two consolidated sleep episodes will still have them when in an environment shielded from external cues, but the rhythm is not entrained to the 24-hour light–dark cycle in nature.

[51] Recent research has influenced the design of spacecraft environments, as systems that mimic the light–dark cycle have been found to be highly beneficial to astronauts.

Norwegian researchers at the University of Tromsø have shown that some Arctic animals (e.g., ptarmigan, reindeer) show circadian rhythms only in the parts of the year that have daily sunrises and sunsets.

[53] A 2006 study in northern Alaska found that day-living ground squirrels and nocturnal porcupines strictly maintain their circadian rhythms through 82 days and nights of sunshine.

[54] The navigation of the fall migration of the Eastern North American monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) to their overwintering grounds in central Mexico uses a time-compensated sun compass that depends upon a circadian clock in their antennae.

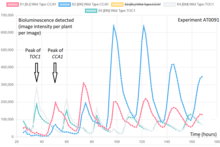

[61][62] When CCA1 and LHY are overexpressed (under constant light or dark conditions), plants become arrhythmic, and mRNA signals reduce, contributing to a negative feedback loop.

[65] Overall, it was found that all the varieties of Arabidopsis thaliana had greater levels of chlorophyll and increased growth in environments whose light and dark cycles matched their circadian rhythm.

[78] The model includes the formation of a nuclear PER-TIM complex which influences the transcription of the PER and the TIM genes (by providing negative feedback) and the multiple phosphorylation of these two proteins.

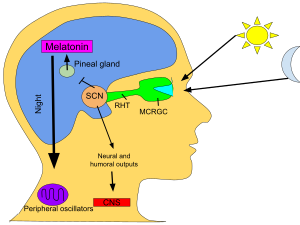

[81] The SCN takes the information on the lengths of the day and night from the retina, interprets it, and passes it on to the pineal gland, a tiny structure shaped like a pine cone and located on the epithalamus.

[84] Early research into circadian rhythms suggested that most people preferred a day closer to 25 hours when isolated from external stimuli like daylight and timekeeping.

The leading edge of circadian biology research is translation of basic body clock mechanisms into clinical tools, and this is especially relevant to the treatment of cardiovascular disease.

[111][112][113][114] Timing of medical treatment in coordination with the body clock, chronotherapeutics, may also benefit patients with hypertension (high blood pressure) by significantly increasing efficacy and reduce drug toxicity or adverse reactions.

[116] Importantly, for rational translation of the most promising Circadian Medicine therapies to clinical practice, it is imperative that we understand how it helps treat disease in both biological sexes.

[127] Circadian rhythms and clock genes expressed in brain regions outside the suprachiasmatic nucleus may significantly influence the effects produced by drugs such as cocaine.

[131][132][133][134] Disruption to rhythms in the longer term is believed to have significant adverse health consequences for peripheral organs outside the brain, in particular in the development or exacerbation of cardiovascular disease.

[135] A number of studies have also indicated that a power-nap, a short period of sleep during the day, can reduce stress and may improve productivity without any measurable effect on normal circadian rhythms.

High levels of the atherosclerosis biomarker, resistin, have been reported in shift workers indicating the link between circadian misalignment and plaque build up in arteries.

[151][149] In humans, shift work that favours irregular eating times is associated with altered insulin sensitivity, diabetes and higher body mass.