Luciferase

[2]Luciferases are widely used in biotechnology, for bioluminescence imaging[3] microscopy and as reporter genes, for many of the same applications as fluorescent proteins.

However, luciferases have been studied in luminous fungi, like the Jack-O-Lantern mushroom, as well as examples in other kingdoms including bioluminescent bacteria, and dinoflagellates.

The luciferases of fireflies – of which there are over 2000 species – and of the other Elateroidea (click beetles and relatives in general) are diverse enough to be useful in molecular phylogeny.

The Metridia longa secreted luciferase gene encodes a 24 kDa protein containing an N-terminal secretory signal peptide of 17 amino acid residues.

[10] At pH 8, it can be seen that the unprotonated histidine residues are involved in a network of hydrogen bonds at the interface of the helices in the bundle that block substrate access to the active site and disruption of this interaction by protonation (at pH 6.3) or by replacement of the histidine residues by alanine causes a large molecular motion of the bundle, separating the helices by 11Å and opening the catalytic site.

Therefore, in order to lower the pH, voltage-gated channels in the scintillon membrane are opened to allow the entry of protons from a vacuole possessing an action potential produced from a mechanical stimulation.

[10] Hence, it can be seen that the action potential in the vacuolar membrane leads to acidification and this in turn allows the luciferin to be released to react with luciferase in the scintillon, producing a flash of blue light.

All luciferases are classified as oxidoreductases (EC 1.13.12.-), meaning they act on single donors with incorporation of molecular oxygen.

First is adenylation, a process in which D-luciferin is converted to D-luciferyl-adenylate (D-AMP) via the covalent addition of adenosine monophosphate to an amino acid side chain.

Studies have presented the first crystal structure of luciferase in its second catalytic conformation using DLSA (5′-O-[N-(dehydroluciferyl)-sulfamoyl]adenosine), a stable analog of D-AMP.

A transition to the oxidation-available conformation involves a ~140° rotation of the C-terminal domain, upon which oxidation initiates formation of the dioxetanone intermediate.

Unlike D-AMP, DLSA cannot undergo oxidation, but the “locking” of the enzyme in its second catalytic conformation allowed researchers to study the oxidation-ready state of luciferase.

[23] Luciferase can additionally be made more sensitive for ATP detection by increasing the luminescence intensity by changing certain amino acid residues in the sequence of the protein.

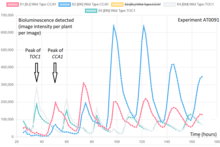

[25] Different types of cells (e.g. bone marrow stem cells, T-cells) can be engineered to express a luciferase allowing their non-invasive visualization inside a live animal using a sensitive charge-couple device camera (CCD camera).This technique has been used to follow tumorigenesis and response of tumors to treatment in animal models.

[26][27] However, environmental factors and therapeutic interferences may cause some discrepancies between tumor burden and bioluminescence intensity in relation to changes in proliferative activity.

The intensity of the signal measured by in vivo imaging may depend on various factors, such as D-luciferin absorption through the peritoneum, blood flow, cell membrane permeability, availability of co-factors, intracellular pH and transparency of overlying tissue, in addition to the amount of luciferase.