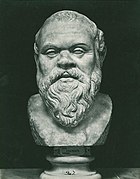

Classical Greek sculpture

[1] The sculpture of Classical Greece developed an aesthetic that combined idealistic values with a faithful representation of nature, while avoiding overly realistic characterization and the portrayal of emotional extremes, generally maintaining a formal atmosphere of balance and harmony.

[2][3] Classicism raised Man to an unprecedented level of dignity, at the same time as it entrusted him with the responsibility of creating his own destiny, offering a model of harmonious life, in a spirit of comprehensive education for an exemplary citizenship.

These values, together with their traditional association of beauty with virtue, found in the sculpture of the Classical period with its idealized portrait of the human being, a particularly apt vehicle for expression, and an efficient instrument of civic, ethical and aesthetic education.

With it, a new form of representation of the human body - influential to this day - began, being one of the cores of the birth of a new philosophical branch, Aesthetics, and the stylistic foundation of later revivalist movements of importance, such as the Renaissance and Neoclassicism.

Apart from its historical value, Classicism's intrinsic artistic quality has had great impact, the vast majority of ancient and modern critics praising it vehemently, and the museums that preserve it being visited by millions of people every year.

The sculpture of Greek Classicism, although sometimes the target of criticism that relates its ideological basis to racial prejudices, aesthetic dogmatism, and other particularities, still plays a positive and renovating role in contemporary art and society.

His role in the history of Greek sculpture stems from his decision to rebuild the city by breaking a vow made by the Athenians to leave in ruins the monuments that had been destroyed by the Persians, as a perennial reminder of barbarism.

The Archaic style made use of several conventions inherited from the Egyptians, and its most important genre, the male nude (the kouros) had a fixed formula: An image of stylized lines that retained from the real human body only the most basic features, that displayed an invariably smiling face and the same bodily attitude.

Around 455 B.C., Myron, a sculptor of the transition, created his Discobolus, a work that already shows a more advanced degree of naturalism, and soon after, around 450 B.C., Polykleitos consolidated a new canon of proportions, a synthesis that convincingly expressed the beauty, harmony and vitality of the body and gave it an aspect of eternity and perennial youth.

Phidias, leading the group of sculptors decorating the Acropolis, left in the reliefs and statuary of the Parthenon the first series of classicist works on a monumental scale, establishing thematic and narrative models that would endure for a long time.

Since art had the function to educate rather than only please, the man it represented had to look good, virtuous, and beautiful, so that such qualities, visibly enshrined in countless statues, would permeate the collective consciousness and determine the adoption of a healthy, harmonious, and positive way of life, ultimately ensuring the happiness of all.

His neutral and dispassionate expression, his balance between staticity and movement (the contrapposto), his care in establishing a strict system of proportions that defined the whole composition of the body figure and the relations of the parts to each other, appeared as a great novelty in his time.

The interpretation of this passage is controversial but it raises a question about the relationship between appearances and truth, and admits the possibility of art expressing pathos, individual emotion, and drama, in direct opposition to the neutrality and restraint of Polykleitos.

For an audience used to seeing in celebratory statues, not a tribute to the individual who served as a model, but a portrait of collective heroism, an example to be followed by all citizens and a service rendered to the whole society, this concept came as a shock, weakening the absolute and invariable character of arete.

The individual sphere of interest became increasingly important, which would be the essence of the art of the 4th century B.C., when Plato and Aristotle would extraordinarily deepen what Socrates had outlined, laying the foundations for the development of an entirely new philosophical branch: Aesthetics.

[34] While the preferences of the expanding market were increasingly opening up to individual taste, Plato's traditionalist and idealistic questionings of the role of mimesis in art, plus his condemnation of the tragic, raised problems for the validation of the artistic product that have not yet been fully resolved.

[35][36][37] The theoretical debate in the transition to Lower Classicism was advanced by Aristotle, whose theory of catharsis contributed to the formulation of a new concept of art liberally avoiding the condemnation of popular culture and its typical emotionalism.

To face these difficulties, later sculptors made use of special resources to keep the distance between gods and men clear, rescuing archaic stylistic traits such as frontality, hieratic posture, impassive and supernatural features, which, in contrast to the increasingly naturalistic and expressive style of profane statuary, delimited well the spheres of the sacred and the mundane and forced the devotee to respect the idol, as a reminder that the divine remains forever essentially unknowable.

When the representation of the deities was not directly linked to the cult, as in monuments and decorative architectural reliefs, there was greater formal freedom, although some of the same conventions were observed and an attempt was made to maintain traits that well identified the divine aspect of the character.

The erotic appeal of his Aphrodite of Knidos – the first completely nude female statue in Greek art – made her famous in her day and gave rise to the prolific typological family of the Venus Pudica.

Scopas became known for the sense of drama, violence, dynamism, and passion with which he imbued his works, especially those he left in the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, the most important Greek architectural achievement in this period, although in others he showed his ability to portray tranquility and harmony.

These masters, along with other notable figures of their generation such as Leochares, Bryaxis, Cephisodotus the Elder, Euphranor, and Timotheus, resolved all outstanding basic difficulties regarding form and technique that might still hinder the free expression of the idea in matter.

Thus, they contributed with great achievements in the process of exploring human anatomy, the representation of clothing, and solving problems of composition, being the link in the passage from the classical to the Hellenistic tradition, as well as bringing the technique of stone carving and bronze modeling to an unprecedented level of quality.

Part of such difficulty is due to the fact that many works are only known through literary references, later copies, are in an incomplete and damaged state, or because their dating and attribution of authorship are often uncertain and the biographies of their creators have multiple gaps and inconsistencies.

[57][58][59][49] Of great value for reconstructing the landscape of Greek sculpture are the miniature copies, which were extremely popular and replicated in smaller scale virtually every formal model and every important work of monumental statuary, a practice that was not limited to the Classical period.

Until this time, immense amounts of sculpture had survived in temples and ancient monuments, but from then on, their ubiquitous nudity began to be seen as an offense to Christian morality, as well as being condemned as diabolical cult images and bad reminders of paganism.

[...] This is the origin of the veneration and awe we have for statues and paintings, and from this derives the reward and honor of Artists; this was the glory of Timantes, Apeles, Phidias and Lysippus, and of so many others renowned for their fame, all who, rising above human forms, achieved with their ideas and works an admirable perfection.

This Idea may then be called the perfection of Nature, the miracle of art, the clairvoyance of the intellect, the example of the mind, the light of imagination, the rising sun, which from the east inspires the statue of Menon, and inflames the monument of Prometheus.

In this sense, the classical model may have a new attraction for artists and society in a context of updating the paideia, rescuing a line of work inspired by classical humanism, focused on the common good and the ethical and integral education of the public to which their works are directed, in a historical moment in which the emphasis on technology, along with consumerism, the excessive specialization of trades, wild urban life, ecological problems, the superficiality of mass culture, and the loss of strong moral references, have become threatening aspects for the well-being and the very survival of the human race.

At least as far as the West is concerned, the appeal that the classical model has held throughout its history and still holds today attests to its persistent ability to stimulate the popular imagination and to be incorporated into a variety of cultural, ethical, social, and political ideologies.