Domitian

[b] As emperor, Domitian strengthened the economy by revaluing the Roman coinage, expanded the border defenses of the empire, and initiated a massive building program to restore the damaged city of Rome.

[17] By the time he was 16 years old, Domitian's mother and sister had long since died,[18] while his father and brother were continuously active in the Roman military, commanding armies in Germania and Judaea.

[19] During the Jewish–Roman wars, he was likely taken under the care of his uncle Titus Flavius Sabinus II, at the time serving as city prefect of Rome; or possibly even Marcus Cocceius Nerva, a loyal friend of the Flavians and the future successor to Domitian.

In his biography in the Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Suetonius attests to Domitian's ability to quote the important poets and writers such as Homer or Virgil on appropriate occasions,[21][22] and describes him as a learned and educated adolescent, with elegant conversation.

[24][25] A detailed description of Domitian's appearance and character is provided by Suetonius, who devotes a substantial part of his biography to his personality: He was tall of stature, with a modest expression and a high colour.

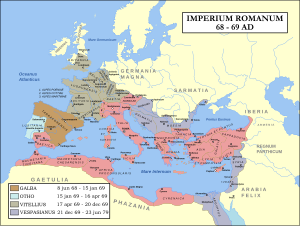

Having spent the greater part of his early life in the twilight of Nero's reign, Domitian's formative years would have been strongly influenced by the political turmoil of the 60s, culminating with the civil war of 69, which brought his family to power.

[36] A strong force drawn from the Judaean and Syrian legions marched on Rome under the command of Mucianus, while Vespasian travelled to Alexandria, leaving Titus in charge of ending the Jewish rebellion.

Terms of peace, including a voluntary abdication, were agreed upon with Titus Flavius Sabinus II but the soldiers of the Praetorian Guard—the imperial bodyguard—considered such a resignation disgraceful and prevented Vitellius from carrying out the treaty.

[42] Strict control was also maintained over the young Caesar's entourage, promoting away Flavian generals such as Arrius Varus and Antonius Primus and replacing them with more reliable men such as Arrecinus Clemens.

In October/November 79, Mount Vesuvius erupted,[67] burying the surrounding cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum under metres of ash and lava; the following year, a fire broke out in Rome that lasted three days and destroyed a number of important public buildings.

[75] In addition to exercising absolute political power, Domitian believed the emperor's role encompassed every aspect of daily life, guiding the Roman people as a cultural and moral authority.

He became personally involved in all branches of the administration: edicts were issued governing the smallest details of everyday life and law, while taxation and public morals were rigidly enforced.

[78] According to Suetonius, the imperial bureaucracy never ran more efficiently than under Domitian, whose exacting standards and suspicious nature maintained historically low corruption among provincial governors and elected officials.

[81] Above all, however, Domitian valued loyalty and malleability in those he assigned to strategic posts, qualities he found more often in men of the equestrian order than in members of the Senate or his own family, whom he regarded with suspicion, and promptly removed from office if they disagreed with imperial policy.

[103] His most significant military contribution was the development of the Limes Germanicus, which encompassed a vast network of roads, forts and watchtowers constructed along the Rhine river to defend the Empire.

[105] Although little information survives of the battles fought, enough early victories were apparently achieved for Domitian to be back in Rome by the end of 83, where he celebrated an elaborate triumph and conferred upon himself the title of Germanicus.

[104] One of the most detailed reports of military activity under the Flavian dynasty was written by Tacitus, whose biography of his father-in-law Gnaeus Julius Agricola largely concerns the conquest of northern Britain between 77 and 84.

[117] Although the Romans inflicted heavy losses on the enemy, two-thirds of the Caledonian army escaped and hid in the Scottish marshes and Highlands, ultimately preventing Agricola from bringing the entire British island under his control.

[129][130] However, not only did he reject the title of Dominus during his reign,[131][132] but since he issued no official documentation or coinage to this effect, historians such as Brian Jones contend that such phrases were addressed to Domitian by flatterers who wished to earn favors from him.

The Senatorial officers may have disapproved of Domitian's military strategies, such as his decision to fortify the German frontier rather than attack, as well as his recent retreat from Britain, and finally the disgraceful policy of appeasement toward Decebalus.

[153] Although little is known about the life and career of Nerva before his accession as Emperor in 96, he appears to have been a highly adaptable diplomat, surviving multiple regime changes and emerging as one of the Flavians' most trusted advisors.

The wounded Emperor put up a fight, but succumbed to seven further stabs, his assailants being a subaltern named Clodianus, Parthenius's freedman Maximus, Satur, a head-chamberlain and one of the imperial gladiators.

The precise facts have been obscured by history,[184] but modern historians believe Nerva was proclaimed Emperor solely on the initiative of the Senate, within hours after the news of the assassination broke.

In many instances, existing portraits of Domitian, such as those found on the Cancelleria Reliefs, were simply recarved to fit the likeness of Nerva, which allowed quick production of new images and recycling of previous material.

[186] According to Suetonius, the people of Rome met the news of Domitian's death with indifference, but the army was much grieved, calling for his deification immediately after the assassination, and in several provinces rioting.

Other passages, alluding to Domitian's love of epigrammatic expression, suggest that he was in fact familiar with classic writers, while he also patronized poets and architects, founded artistic Olympics, and personally restored the library of Rome at great expense after it had burned down.

[54][194] Modern historians consider this highly implausible however, noting that malicious rumours such as those concerning Domitia's alleged infidelity were eagerly repeated by post-Domitianic authors, and used to highlight the hypocrisy of a ruler publicly preaching a return to Augustan morals, while privately indulging in excesses and presiding over a corrupt court.

Several modern authors such as Dorey have argued the opposite: that Agricola was in fact a close friend of Domitian, and that Tacitus merely sought to distance his family from the fallen dynasty once Nerva was in power.

[198] Other influential 2nd century authors include Juvenal and Pliny the Younger, the latter of whom was a friend of Tacitus and in 100 delivered his famous Panegyricus Traiani before Trajan and the Roman Senate, exalting the new era of restored freedom while condemning Domitian as a tyrant.

Hostile views of Domitian had been propagated until archeological and numismatic advances brought renewed attention to his reign, and necessitated a revision of the literary tradition established by Tacitus and Pliny.