History of the Malay language

The oldest form of Malay is descended from the Proto-Malayo-Polynesian language spoken by the earliest Austronesian settlers in Southeast Asia.

This form would later evolve into Old Malay when Indian cultures and religions began penetrating the region, most probably using the Kawi and Rencong scripts, some linguistic researchers say.

From the 19th to 20th century, Malay evolved progressively through significant grammatical improvements and lexical enrichment into a modern language with more than 800,000 phrases in various disciplines.

Its ancestor, the Proto-Malayo-Polynesian language that derived from Proto-Austronesian, began to break up by at least 2000 BCE as a result possibly by the southward expansion of Austronesian peoples into the Philippines, Borneo, Maluku and Sulawesi from the island of Taiwan.

Linguists generally agree that the homeland of the Malayic languages is in Borneo, based on its geographic spread in the interior, its variations that are not due to contact-induced change, and its sometimes conservative character.

[5] The Old Malay system is greatly influenced by Sanskrit scriptures in terms of phonemes, morphemes, vocabulary and the characteristics of scholarship, particularly when the words are closely related to Indian culture such as puja, bakti, kesatria, maharaja and raja, as well as on the Hindu-Buddhist religion such as dosa, pahala, neraka, syurga or surga (used in Indonesia-which was based on Malay), puasa, sami and biara, which lasts until today.

[6] This is due to the existence of a number of morphological and syntactic peculiarities, and affixes that are familiar from the related Batak language but are not found even in the oldest manuscripts of Classical Malay.

It may be the case that the language of the Srivijayan inscriptions is a close cousin rather than an ancestor of Classical Malay according to Teeuws, hence he asked for more research about it.

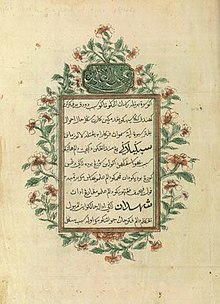

[9][10] The period of Classical Malay started when Islam gained its foothold in the region and the elevation of its status to a state religion.

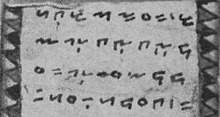

The earliest instances of Arabic lexicons incorporated in the pre-Classical Malay written in Kawi was found in the Minye Tujoh inscription dated 1380 CE from Aceh in Sumatra.

Both inscriptions not only serve as the evidence of Islam as a state religion but also as the oldest surviving specimen of the dominant classical orthographic form, the Jawi script.

Similar inscriptions containing various adopted Arabic terms with some of them still written the Indianised scripts were also discovered in other parts of Sumatra and Borneo.

[14] More loan words from Arab, Persian, Tamil and Chinese were absorbed and the period witnessed the flowering of Classical Malay literature as well as professional development in royal leadership and public administration.

[12][15] Malacca's success as a centre of commerce, religion, and literary output has made it an important point of cultural reference to the many influential Malay sultanates in the later centuries.

In fact, Johor even played a key role in the introduction of the Malay language to various areas in the eastern part of the archipelago.

[18] Apart from being the primary instrument in spreading Islam and commercial activities, Malay also became a court and literary language for kingdoms beyond its traditional realm like Aceh and Ternate and also used in diplomatic communications with the European colonial powers.

[19] This era also witnessed the growing interest among foreigners in learning the Malay language for the purpose of commerce, diplomatic missions and missionary activities.

The oldest of these was a Chinese-Malay word list compiled by the Ming officials of the Bureau of Translators during the heyday of Malacca Sultanate.

The dictionary was known as Man-la-jia Yiyu (滿剌加譯語, Translated Words of Malacca) and contains 482 entries categorised into 17 fields namely astronomy, geography, seasons and times, plants, birds and animals, houses and palaces, human behaviours and bodies, gold and jewelleries, social and history, colours, measurements and general words.

[20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][excessive citations] In the 16th century, the word-list is believed still in use in China when a royal archive official Yang Lin reviewed the record in 1560 CE.

[35] In fact, Francis Xavier devoted much of his life to missions in just four main centres, Malacca, Amboina and Ternate, Japan and China, two of those were within Malay speaking realm.

In facilitating missionary works, religious books and manuscripts began to be translated into Malay of which the earliest was initiated by a pious Dutch trader, Albert Ruyll in 1611.

Many other well-known books were published throughout the archipelago such as three notable classical literary works, Gurindam Dua Belas (1847), Bustanul Katibin (1857) and Kitab Pengetahuan Bahasa (1858) by Selangor-born Raja Ali Haji were also produced in Riau-Lingga during this time.

This development generated the writing of textbooks for schools, in addition to the publication of reference materials such as Malay dictionaries and grammar books.

The appreciation of the language grew, and various efforts were undertaken by the community to further enhance the usage of Malay as well as to improve its abilities in facing the challenging modern era.

Among the efforts done was the planning of a corpus for the Malay language, first initiated by the Pakatan Belajar-Mengajar Pengetahuan Bahasa (Society for the Learning and Teaching of Linguistic Knowledge), established in 1888.

The emergence of these newly independent states paved the way for a broader and widespread use of Malay and Indonesian in government administration and education.

Indonesian generally uses Latin and Greek-based international terms, while Malay in Malaysia, under the guidance of its first Language Board director Syed Nasir, was more conservative and would accept foreign words only as a last resort.