History of Interlingue

De Wahl ended up becoming one of the earliest users of Esperanto, which he encountered for the first time in 1888 during his period as a Volapükist and for which he was in the process of composing a dictionary of marine terms.

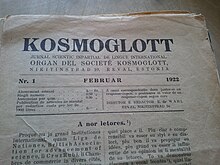

[14]Edgar de Wahl announced the creation of Occidental in 1922 with the first issue of the magazine Cosmoglotta, published in Tallinn, Estonia under the name Kosmoglott.

"[18]De Wahl also corresponded with Italian mathematician Giuseppe Peano, creator of Latino sine flexione, gaining an appreciation for its selection of international vocabulary.

"I believe the "Vocabulario commune" book by Professor Peano to already be a more valuable and scientific work than the entire scholastic literature of Ido on imaginary things evoked by the "fundamento" of Zamenhof", he wrote.

[19][20] De Wahl had not intended to announce the language for a few years; after hearing that the League of Nations (LON) had begun an inquiry into the question of an international language he decided to accelerate its release[21] and after receiving a favorable reply the year before from Under-Secretary General Nitobe Inazō of the LON which had adopted a resolution on the subject in 1921.

[28] The name was changed to Cosmoglotta in 1927 as it began to officially promote Occidental in lieu of other languages, and that January the magazine's editorial and administrative office was moved to the Vienna neighborhood of Mauer, now part of Liesing.

Originally entitled Cosmoglotta-Informationes,[40] it was soon renamed Cosmoglotta B, focusing on items of more internal interest such as linguistic issues, reports of Occidental in the news, and financial updates.

[51][52] Unaware of this, de Wahl was bewildered at the lack of response to his continued letters; even a large collection of poetry translated into Occidental was never delivered.

De Wahl himself was incarcerated for a time after refusing to leave Estonia for Germany, and later took refuge in a psychiatric hospital where he lived out his life.

The other centers of Occidental activity in Europe did not fare as well, with the stocks of study materials in Vienna and Tallinn having been destroyed in bombings[62] and numerous Occidentalists sent to concentration camps in Germany and Czechoslovakia.

[63][64] Contacts were reestablished shortly after the war by those who remained, with letters from countries such as France, Czechoslovakia, Finland and Great Britain reaching Cosmoglotta.

With questions still remaining about the official form of some words and a lack of general material destined for the general public,[76] much time during World War II was spent on language standardization and course creation, and due to the continuing war, in August 1943 the decision was made to create an interim academy to officialize this process.

[77][78] While doing so, they frequently found themselves confronted with the decision between two "theoretically equally good" forms that had remained in popular usage, but whose presence could be confusing to a new learner of the language.

Its co-founder Alice Vanderbilt Morris was an Esperantist, as were many of its staff,[82] and many Occidentalists including de Wahl himself[82] believed that its leadership under Esperantist William Edward Collinson (known among readers of Cosmoglotta for an article of his entitled "Some weak points of Occidental")[83] meant that it had been set up with a staff of professional linguists under a neutral and scientific pretext to bolster a final recommendation for Esperanto.

Ric Berger was particularly positive in describing the language the IALA was creating as a victory for the natural school ("Li naturalitá esset victoriosi!

[87] He also feared that it might simply "disperse the partisans of the natural language with nothing to show for it" after Occidental had created "unity in the naturalistic school" for so long.

Interlingua also allowed optional irregular verbal conjugations such as so, son and sia[91] as the first-person singular, third-person plural and subjunctive form of esser, the verb 'to be'.

[92][93] The magazine was financially strained by inflated postwar printing costs and its inability to collect payments from certain countries,[94] a marked contrast to the well-funded[95] New York-based IALA.

The beginning of the Cold War created a particularly uncomfortable situation for the Occidental-Union,[97][98][99] whose name coincided with that of an anti-Russian political league; the Swiss Occidentalists believed that was why all of de Wahl's letters from Tallinn were intercepted.

Vĕra Barandovská-Frank's perception of the situation at the time was as follows (translated from Esperanto): In the field of naturalistic planned languages Occidental-Interlingue was until then unchallenged (especially after the death of Otto Jespersen, author of Novial), as all new projects were nearly imitations of it.

This applied to Interlingua as well, but it carried with it a dictionary of 27 000 words put together by professional linguists that brought great respect, despite in principle only confirming the path that de Wahl had started.

The first proposition was not accepted, but the second was, giving a practical collaboration and support to Interlingua.André Martinet, the second-last director of the IALA, made similar observations to those of Matejka.

In these circumstances the efforts by Ric Berger to move all users of Interlingue en masse to Interlingua de IALA was a shock.

In spite of attempts by diehard supporters of Occidental to stave off the inevitable — for instance, by such tactics as renaming their language Interlingue — most remaining Occidentalists made the short pilgrimage to the shrine of Interlingua.

Barandovská-Frank believed that the ebb in interest in Occidental-Interlingue occurred in concert with the aging of the generation that was first drawn to it from other planned languages (translated from Esperanto): Most of those interested in Interlingue belonged to the generation that became acquainted in turn with Volapük, Esperanto and Ido, later on finding the most aesthetic (essentially naturalistic) solution in Occidental-Interlingue.

Many subsequently moved to IALA's Interlingua, which however did not prove to be much more successful despite the impression its scientific origin made, and those who remained loyal to Occidental-Interlingue did not succeed in imparting their enthusiasm to a new generation.

[114] One example is The Esperanto Book released in 1995 by Harlow, who wrote that Occidental had an intentional emphasis on European forms and that some of its leading followers espoused a Eurocentric philosophy, which may have hindered its spread.