Climate communication

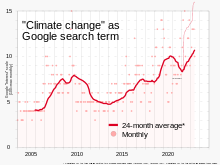

Research in the field emerged in the 1990s and has since grown and diversified to include studies concerning the media, conceptual framing, and public engagement and response.

Since the late 2000s, a growing number of studies have been conducted in countries in the Global South and have been focused on climate communication with marginalized populations.

[4][7] This expansion has legitimated climate change communication as its own academic field and has yielded a group of experts specific to it.

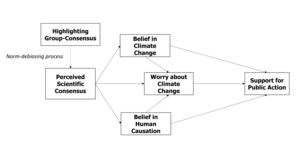

[9][10] A 2020 study by Kris De Meyer et al. attempts to push back against that notion and argues that action produces belief.

[9][11] Perception is often related to personal recognition to impacted locations, times (the present vs. the future), weather events, or economics, which has placed emphasis on different methods of framing (linking concepts) and rhetoric when communicating.

[8][9] Understanding and relating to the audiences' moral, cultural, religious, and political values, identities, and emotions (like fear) are viewed as imperative to appropriate and effective communication because climate change can otherwise seem intangible due to uncertainty and distance (physical, social, temporal).

[11] Some politicians, such as Arnold Schwarzenegger with his slogan "terminate pollution", say that activists should generate optimism by focusing on the health co-benefits of climate action.

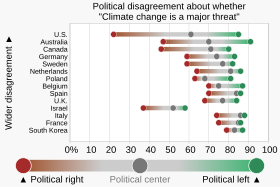

[24] Additionally, climate denialism by organizations, such as The Heartland Institute in the United States,[25][26][27] and individuals introduces misinformation into public discourse and understanding.

In fact, too much information can do the exact opposite because people tend to neglect global warming once they realize there is no easy solution.

[43] Major segmentation studies include: A significant part of the research and public advocacy conversations about climate change have focused on the effectiveness of different terms used to describe "global warming".

More recently, the focus has shifted to rhetoric describing all aspects and effects of climate change, including human-non-human relationships.

are expressed in legislation can, in the view of University of Waterloo Professor, Jennifer Clary-Lemon, be damaging to perceptions as they seem to carry a persuasive tone, in favor of seeing these pieces of nature as less than; not recognizing their importance.

Experts believe research needs to be done in this area and then it could be applied to climate communication and could be effective in creating better messaging that spurs greater engagement and action.

[36] A December 2008 article in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine recommended using two broad sets of tools to effect this change: communication and social marketing.

[66] The researchers propose that these climate stories spark action by allowing each experimental subject to process the information experientially, increasing their affective engagement and leading to emotional arousal.

The effect of mass media and journalism on the public's attitudes towards climate change has been a significant part of communications studies.

A 2009 handbook developed by the Center for Research on Environmental Decisions at the Earth Institute at Columbia University describes eight main principles for communications based on the psychological research about Environmental decisions:[69] A strategy playbook, developed based on lessons learned from the COVID pandemic communication, was released On Road Media in the UK in 2020.

The framework is focused on developing positive messages that help people feel optimistic about learning more to address climate change.

It is based on extensive social studies research exploring the impact of different tactics for climate communication.

[71] The guidelines focus on six main principles: A 2018 study concluded that graphical illustrations such as charts and graphs more effectively overcome misperceptions than the same information presented in text.

[73] They recommend that visual communications include: Psychologists have increasingly been assisting the worldwide community in facing the difficult challenge of organizing effective climate change mitigation efforts.

For example, Christiana Figueres and Tom Rivett-Carnac, who led the efforts to organize the unprecedentedly successful 2015 Paris Agreement, have since campaigned to spread the view that a "stubborn optimism" mindset should ideally be part of an individual's psychological response to the climate change challenge.

[80] However, the researchers stated that people's math anxiety and level of mathematical ability suggested limiting the quantity of numerical information that should be presented.

[80] The impacts of climate change are exacerbated in low- and middle income countries; higher levels of poverty, less access to technologies, and less education, means that this audience needs different information.