Codex Azcatitlan

[3] Mexican historian Federico Navarrete [es] noted the use of European methods to depict the codex's content[4] such as the use of three-dimensional objects.

[5] The codex's construction combines the pre-Columbian Aztec method of accordion-folding, but is bound in the two-page European style.

[11] It appears that the master tlacuilo drew each set of specific year glyphs (Reed, Flint, House, Rabbit) in one session.

Historian María Castañeda de la Paz has proposed the second half of the 16th century as the window of time in which Codex Azcatitlan was authored.

A decade later, Donald Robertson challenged the proposition that the senior tlacuiloque produced the colonial history segments by himself.

[4] Codex Azcatitlan is divided into four sections,[16] but records in one narrative the history of the Mexica people from their migration from Aztlán to about 1527, just after the death of Cuauhtémoc.

[16] The final segment displays earlier colonial Mexican history and is broken into vertical columns that run from left to right.

[19] The glosses, in alphabetic Nahuatl, appear mostly in the migration segment to describe places and characters, though they occasionally help translate the year glyphs for readers not familiar with pre-Conquest Aztec writing.

[20] This segment has, unlike earlier manuscripts such as the Boturini Codex, depictions of the migration, such as their stops at sources of fresh water, getting lost, building temples, and attacks by wild animals.

[27] The first page of the codex, folio 1 recto (1r), shows the three rulers of the Triple Alliance, sitting upon European-style thrones in native dress and holding staves of office.

[28] The migration begins on the next page, folio 1 vecto (1v), with the departure of the Azteca from their island homeland Aztlán, as commanded by their god, Huitzilopochtli,[21] who appears nearby as a warrior in a hummingbird headdress.

[29] Also present on folio 1v is a glyph of an ant surrounded by dots and, above it, the gloss from which the codex derives its name, which reads "Ascatitla".

Emerging from this glyph is a horn, yet another reference to Tlateloco, whose first ruler was the son of the tlatoani of Azcapotzalco ("Place of the Anthill").

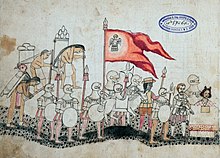

[31] They also meet eight tribes, the Huexotzinca, Chalca, Xochimilca, Cuitlihuaca, Malinalca, Chichimeca, Tepaneca, and the Matlatzinca,[32] who wish to accompany the Azteca on their migration.

The latter agree and the nine tribes depart, led by four 'god-bearers' named Chimalma, Apanecatl, Cuauhcoatl, and Tezcacoatl, each carrying a tlaquimilolli.

The migration segment ends on the next page with the foundation of Tenochtitlan (left; 12v) and Tlatelolco (13r) and the selection of their respective tlatoani.

[37] Three glosses, the last in the codex, appear on folios 13v to 15r to elucidate some matters of Tepanec history, such as the coronation and death of Maxtla of Azcapotzalco.

[44] The segment has strong narrative similarity to other indigenous accounts of the Conquest, namely book 12 of the Florentine Codex and the Annals of Tlateloco.

Behind Cortés stands his army, rendered as eight conquistadors, an African slave, a horse, and three native men carrying supplies while Malinche translates for him.

Who she speaks to is made unclear by the loss of the next page, but it is probable that the event depicted is Cortés's meeting with Moctezuma II outside Tenochtitlan on 8 November 1519.

As indicated by the ship, the scene is of a failed attack in May 1521 led by Alvarado that nearly saw Cortés captured while he was attempting to save drowning Spaniards.

[57] Next the elite of Tlatelolco are shown leaving the city to resettle under Spanish rule beneath a glyph for Amaxac, where Cuauhtemoc surrendered.

[59] Following the priests are a series of images (digging stick, wood, water) that symbolize the reconstruction of Tenochtitlan-Tlatelolco as Mexico City under Tlacotl,[60] whose name is represented by the hand grasping an animal's head.

[62] The time of Cuauhtemoc's death, the ritual month of Tozoztontli, is marked by the tlacuilo in the upper-right corner of folio 24v.

[64] Mexicatl Cozoololtic watches from afar as a Mayan lord,[63] possibly Paxbolonacha,[65] brings drums out of a building for a celebration at Acallan.

Salazar and Chirino seized Cortés's estate and then murdered his cousin Rodrigo de Paz, depicted as the corpse in the top right in the Church of San Francisco in Mexico City.

[69] The final extant page of Codex Azcatitlan, folio 25v, records the arrival of Mexico's first bishop, Julián Garcés and the torture of native persons for the location of Moctezoma's treasure.

[70] The page begins with a heavily damaged rendering of a meteorological event and a death by stoning in the ritual month of Atlcahualo.

Garcés and an entourage that includes a seated tlatoani cover the upper half of the page and a mounted woman in the bottom left corner.