Codon usage bias

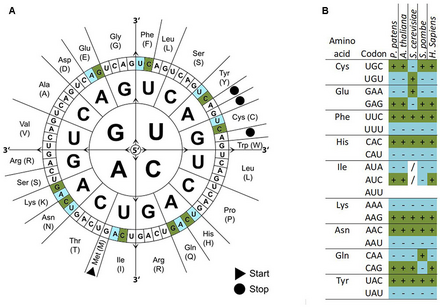

The genetic codes of different organisms are often biased towards using one of the several codons that encode the same amino acid over the others—that is, a greater frequency of one will be found than expected by chance.

[4] [5] [6] Optimal codons in fast-growing microorganisms, like Escherichia coli or Saccharomyces cerevisiae (baker's yeast), reflect the composition of their respective genomic transfer RNA (tRNA) pool.

[10][11] Organisms that show an intermediate level of codon usage optimization include Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly), Caenorhabditis elegans (nematode worm), Strongylocentrotus purpuratus (sea urchin), and Arabidopsis thaliana (thale cress).

[12] Several viral families (herpesvirus, lentivirus, papillomavirus, polyomavirus, adenovirus, and parvovirus) are known to encode structural proteins that display heavily skewed codon usage compared to the host cell.

[citation needed] Different factors have been proposed to be related to codon usage bias, including gene expression level (reflecting selection for optimizing the translation process by tRNA abundance), guanine-cytosine content (GC content, reflecting horizontal gene transfer or mutational bias), guanine-cytosine skew (GC skew, reflecting strand-specific mutational bias), amino acid conservation, protein hydropathy, transcriptional selection, RNA stability, optimal growth temperature, hypersaline adaptation, and dietary nitrogen.

One explanation revolves around the selectionist theory, in which codon bias contributes to the efficiency and/or accuracy of protein expression and therefore undergoes positive selection.

[20] To reconcile the evidence from both mutational pressures and selection, the prevailing hypothesis for codon bias can be explained by the mutation-selection-drift balance model.

Codon usage in noncoding DNA regions can therefore play a major role in RNA secondary structure and downstream protein expression, which can undergo further selective pressures.

In particular, strong secondary structure at the ribosome-binding site or initiation codon can inhibit translation, and mRNA folding at the 5’ end generates a large amount of variation in protein levels.

Because tRNA pools vary between different organisms, the rate of transcription and translation of a particular coding sequence can be less efficient when placed in a non-native context.

For an overexpressed transgene, the corresponding mRNA makes a large percent of total cellular RNA, and the presence of rare codons along the transcript can lead to inefficient use and depletion of ribosomes and ultimately reduce levels of heterologous protein production.

Furthermore, synonymous mutations have been shown to have significant consequences in the folding process of the nascent protein and can even change substrate specificity of enzymes.

These studies suggest that codon usage influences the speed at which polypeptides emerge vectorially from the ribosome, which may further impact protein folding pathways throughout the available structural space.