Work hardening

Some materials cannot be work-hardened at low temperatures, such as indium,[4] however others can be strengthened only via work hardening, such as pure copper and aluminum.

Certain alloys are more prone to this than others; superalloys such as Inconel require materials science machining strategies that take it into account.

An example of desirable work hardening is that which occurs in metalworking processes that intentionally induce plastic deformation to exact a shape change.

[6] Cold forming techniques are usually classified into four major groups: squeezing, bending, drawing, and shearing.

Applications include the heading of bolts and cap screws and the finishing of cold rolled steel.

Such deformation increases the concentration of dislocations which may subsequently form low-angle grain boundaries surrounding sub-grains.

The effects of cold working may be reversed by annealing the material at high temperatures where recovery and recrystallization reduce the dislocation density.

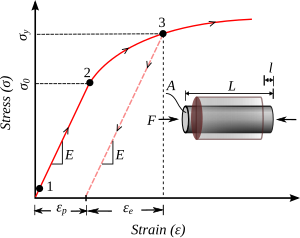

A material's work hardenability can be predicted by analyzing a stress–strain curve, or studied in context by performing hardness tests before and after a process.

Ductility is the ability of a material to undergo plastic deformations before fracture (for example, bending a steel rod until it finally breaks).

This is because under compression, most materials will experience trivial (lattice mismatch) and non-trivial (buckling) events before plastic deformation or fracture occur.

At that point, the material is permanently deformed and fails to return to its original shape when the force is removed.

Plastic deformation, on the other hand, breaks inter-atomic bonds, and therefore involves the rearrangement of atoms in a solid material.

Upon application of stresses just beyond the yield strength of the non-cold-worked material, a cold-worked material will continue to deform using the only mechanism available: elastic deformation, the regular scheme of stretching or compressing of electrical bonds (without dislocation motion) continues to occur, and the modulus of elasticity is unchanged.

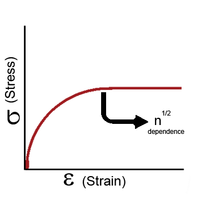

As shown in Figure 1 and the equation above, work hardening has a half root dependency on the number of dislocations.

(Here we discuss true stress in order to account for the drastic decrease in diameter in this tensile test.)

The work-hardened steel bar has a large enough number of dislocations that the strain field interaction prevents all plastic deformation.

Ludwik's equation is similar but includes the yield stress[11]: If a material has been subjected to prior deformation (at low temperature) then the yield stress will be increased by a factor depending on the amount of prior plastic strain ε0: The constant K is structure dependent and is influenced by processing while n is a material property normally lying in the range 0.2–0.5.

Typically, an increase in cold work results in a decrease in the strain hardening exponent[citation needed].

Similarly, high strength steels tend to exhibit a lower strain hardening exponent[citation needed].

The technique of repoussé exploits these properties of copper, enabling the construction of durable jewelry articles and sculptures (such as the Statue of Liberty).

Much gold jewelry is produced by casting, with little or no cold working; which, depending on the alloy grade, may leave the metal relatively soft and bendable.

However, a jeweler may intentionally use work hardening to strengthen wearable objects that are exposed to stress, such as rings.

Items made from aluminum and its alloys must be carefully designed to minimize or evenly distribute flexure, which can lead to work hardening and, in turn, stress cracking, possibly causing catastrophic failure.