Hooke's law

Hooke's equation holds (to some extent) in many other situations where an elastic body is deformed, such as wind blowing on a tall building, and a musician plucking a string of a guitar.

Hooke's law is only a first-order linear approximation to the real response of springs and other elastic bodies to applied forces.

On the other hand, Hooke's law is an accurate approximation for most solid bodies, as long as the forces and deformations are small enough.

For this reason, Hooke's law is extensively used in all branches of science and engineering, and is the foundation of many disciplines such as seismology, molecular mechanics and acoustics.

It is also the fundamental principle behind the spring scale, the manometer, the galvanometer, and the balance wheel of the mechanical clock.

In this general form, Hooke's law makes it possible to deduce the relation between strain and stress for complex objects in terms of intrinsic properties of the materials they are made of.

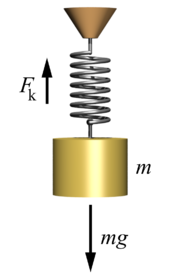

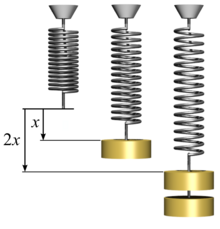

[4] According to this formula, the graph of the applied force Fs as a function of the displacement x will be a straight line passing through the origin, whose slope is k. Hooke's law for a spring is also stated under the convention that Fs is the restoring force exerted by the spring on whatever is pulling its free end.

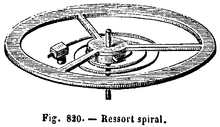

It states that the torque (τ) required to rotate an object is directly proportional to the angular displacement (θ) from the equilibrium position.

It describes the relationship between the torque applied to an object and the resulting angular deformation due to torsion.

Mathematically, it can be expressed as: Where: Just as in the linear case, this law shows that the torque is proportional to the angular displacement, and the negative sign indicates that the torque acts in a direction opposite to the angular displacement, providing a restoring force to bring the system back to equilibrium.

Hooke's spring law usually applies to any elastic object, of arbitrary complexity, as long as both the deformation and the stress can be expressed by a single number that can be both positive and negative.

Hooke's law also applies when a straight steel bar or concrete beam (like the one used in buildings), supported at both ends, is bent by a weight F placed at some intermediate point.

With respect to an arbitrary Cartesian coordinate system, the force and displacement vectors can be represented by 3 × 1 matrices of real numbers.

Therefore, Hooke's law F = κX can be said to hold also when X and F are vectors with variable directions, except that the stiffness of the object is a tensor κ, rather than a single real number k. The stresses and strains of the material inside a continuous elastic material (such as a block of rubber, the wall of a boiler, or a steel bar) are connected by a linear relationship that is mathematically similar to Hooke's spring law, and is often referred to by that name.

The stiffness tensor c, on the other hand, is a property of the material, and often depends on physical state variables such as temperature, pressure, and microstructure.

Therefore, the spring constant k, and each element of the tensor κ, is measured in newtons per meter (N/m), or kilograms per second squared (kg/s2).

For continuous media, each element of the stress tensor σ is a force divided by an area; it is therefore measured in units of pressure, namely pascals (Pa, or N/m2, or kg/(m·s2).

Objects that quickly regain their original shape after being deformed by a force, with the molecules or atoms of their material returning to the initial state of stable equilibrium, often obey Hooke's law.

Steel exhibits linear-elastic behavior in most engineering applications; Hooke's law is valid for it throughout its elastic range (i.e., for stresses below the yield strength).

Rubber is generally regarded as a "non-Hookean" material because its elasticity is stress dependent and sensitive to temperature and loading rate.

Its tensile stress σ is linearly proportional to its fractional extension or strain ε by the modulus of elasticity E:

A direct method exists for calculating the compliance constant for any internal coordinate of a molecule, without the need to do the normal mode analysis.

By pulling slightly on the mass and then releasing it, the system will be set in sinusoidal oscillating motion about the equilibrium position.

This phenomenon made possible the construction of accurate mechanical clocks and watches that could be carried on ships and people's pockets.

Physical equations involving isotropic materials must therefore be independent of the coordinate system chosen to represent them.

A common form of Hooke's law for isotropic materials, expressed in direct tensor notation, is [11]

In terms of Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio, Hooke's law for isotropic materials can then be expressed as

If in addition, since the displacement gradient and the Cauchy stress are work conjugate, the stress–strain relation can be derived from a strain energy density functional (U), then

To do this we take advantage of the symmetry of the stress and strain tensors and express them as six-dimensional vectors in an orthonormal coordinate system (e1,e2,e3) as

where Under plane stress conditions, σzz = σzx = σyz = 0, Hooke's law for an orthotropic material takes the form

- Ultimate strength

- Yield strength (yield point)

- Rupture

- Strain hardening region

- Necking region

- Apparent stress ( F / A 0 )

- Actual stress ( F / A )