Colley Cibber

He wrote 25 plays for his own company at Drury Lane, half of which were adapted from various sources, which led Robert Lowe and Alexander Pope, among others, to criticise his "miserable mutilation" of "crucified Molière [and] hapless Shakespeare".

Cibber's brash, extroverted personality did not sit well with his contemporaries, and he was frequently accused of tasteless theatrical productions, shady business methods, and a social and political opportunism that was thought to have gained him the laureateship over far better poets.

His importance in British theatre history rests on his being one of the first in a long line of actor-managers, on the interest of two of his comedies as documents of evolving early 18th-century taste and ideology, and on the value of his autobiography as a historical source.

[3] He was educated at the King's School, Grantham, from 1682 until the age of 16, but failed to win a place at Winchester College, which had been founded by his maternal ancestor William of Wykeham.

[5] After the revolution, and at a loose end in London, he was attracted to the stage and in 1690 began work as an actor in Thomas Betterton's United Company at the Drury Lane Theatre.

[21] For the early part of Cibber's career, it is unreliable in respect of chronology and other hard facts, understandably, since it was written 50 years after the events, apparently without the help of a journal or notes.

[24] It went through four editions in his lifetime, and more after his death, and generations of readers have found it an amusing and engaging read, projecting an author always "happy in his own good opinion, the best of all others; teeming with animal spirits, and uniting the self-sufficiency of youth with the garrulity of age.

[26] "The first Thing that enters into the Head of a young Actor", he wrote in his autobiography half a century later, "is that of being a Hero: In this Ambition I was soon snubb'd by the Insufficiency of my Voice; to which might be added an uninform'd meagre Person ... with a dismal pale Complexion.

However, his performances of such parts never pleased audiences, which wanted to see him typecast as an affected fop, a kind of character that fitted both his private reputation as a vain man, his exaggerated, mannered style of acting, and his habit of ad libbing.

[9] Pope mentions the audience jubilation that greeted the small-framed Cibber donning Lord Foppington's enormous wig, which would be ceremoniously carried on stage in its own sedan chair.

[9] His tragic efforts, however, were consistently ridiculed by contemporaries: when Cibber in the role of Richard III made love to Lady Anne, the Grub Street Journal wrote, "he looks like a pickpocket, with his shrugs and grimaces, that has more a design on her purse than her heart".

[34] After he had sold his interest in Drury Lane in 1733 and was a wealthy man in his sixties, he returned to the stage occasionally to play the classic fop parts of Restoration comedy for which audiences appreciated him.

Critic John Hill in his 1775 work The actor, or, A treatise on the art of playing, described Cibber as "the best Lord Foppington who ever appeared, was in real life (with all due respect be it spoken by one who loves him) something of the coxcomb".

[40] According to Paul Parnell, Love's Last Shift illustrates Cibber's opportunism at a moment in time before the change was assured: fearless of self-contradiction, he puts something for everybody into his first play, combining the old outspokenness with the new preachiness.

[41] The central action of Love's Last Shift is a celebration of the power of a good woman, Amanda, to reform a rakish husband, Loveless, by means of sweet patience and a daring bed-trick.

[43] Some contemporaries regarded it as moving and amusing, others as a sentimental tear-jerker, incongruously interspersed with sexually explicit Restoration comedy jokes and semi-nude bedroom scenes.

Modern scholars often endorse the criticism that was levelled at Love's Last Shift from the first, namely that it is a blatantly commercial combination of sex scenes and drawn-out sentimental reconciliations.

[51]Richard III was followed by another adaptation, the comedy Love Makes a Man, which was constructed by splicing together two plays by John Fletcher: The Elder Brother and The Custom of the Country.

The turning point of the action, known as "the Steinkirk scene", comes when his wife finds him and a maidservant asleep together in a chair, "as close an approximation to actual adultery as could be presented on the 18th-century stage".

Although it has now joined Love's Last Shift as a forgotten curiosity, it kept a respectable critical reputation into the 20th century, coming in for serious discussion both as an interesting example of doublethink,[55] and as somewhat morally or emotionally insightful.

[68] Cibber's career as both actor and theatre manager is important in the history of the British stage because he was one of the first in a long and illustrious line of actor-managers that would include Garrick, Henry Irving, and Herbert Beerbohm Tree.

The three actors squeezed out the previous owners in a series of lengthy and complex manoeuvres, but after Rich's letters patent were revoked, Cibber, Doggett and Wilks were able to buy the company outright and return to the Theatre Royal by 1711.

[72] Cibber had learned from the bad example of Christopher Rich to be a careful and approachable employer for his actors, and was not unpopular with them; however, he made enemies in the literary world because of the power he wielded over authors.

[76] Cibber's appointment as Poet Laureate in December 1730 was widely assumed to be a political rather than artistic honour, and a reward for his untiring support of the Whigs, the party of Prime Minister Robert Walpole.

[78] His 30 birthday odes for the royal family and other duty pieces incumbent on him as Poet Laureate came in for particular scorn, and these offerings would regularly be followed by a flurry of anonymous parodies,[79] some of which Cibber claimed in his Apology to have written himself.

[78] In the 20th century, D. B. Wyndham-Lewis and Charles Lee considered some of Cibber's laureate poems funny enough to be included in their classic "anthology of bad verse", The Stuffed Owl (1930).

[9][81] From the beginning of the 18th century, when Cibber first rose to be Rich's right-hand man at Drury Lane, his perceived opportunism and brash, thick-skinned personality gave rise to many barbs in print, especially against his patchwork plays.

[87] In the first version of his landmark literary satire Dunciad (1728), Pope referred contemptuously to Cibber's "past, vamp'd, future, old, reviv'd, new" plays, produced with "less human genius than God gives an ape".

Apart from the personal quarrel, Pope had reasons of literary appropriateness for letting Cibber take the place of his first choice of King, Lewis Theobald.

Additionally, Cibber consistently fails to see fault in his own character, praises his vices, and makes no apology for his misdeeds; so it was not merely the fact of the autobiography, but the manner of it that shocked contemporaries.

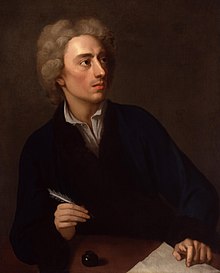

![Sheet of paper advertising the performance of a comedy at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, inscribed: "For the Benefit of MRS SAUNDERS // By His Majesty's Company of Comedians. // AT THE // THEATRE ROYAL // In Drury-Lane : // On MONDAY the 14th Day of April, // will be presented, // A COMEDY call'd, // Rule a Wife, and Have a Wife. // With Entertainments of Singing and Dancing, // as will be Express'd in the Great Bill. // To begin exactly at Six a Clock // (two further lines of text mostly illegible) [By His Majesties?] Command, No Persons are to be admitted behind the // ... [...ney] to be Return'd after ...](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e4/Drury_Lane_playbill_1725.jpg/220px-Drury_Lane_playbill_1725.jpg)