Colonial war

Once a foothold has been established by an incoming power, it may launch expeditions into neighboring territory in retaliation against hostility or to neutralize a potential enemy.

[9] The meanings of defeat and victory were usually more complicated in colonial wars, as in many cases the invading power would face a belligerent that was not encapsulated by a city, government or ruler.

To counter this colonial armies would establish or rebuild markets, schools and other public entities following a conflict, as the Americans did in the Philippines following the Spanish–American War.

[15] Colonial warfare became prevalent in the late 15th century as European powers increasingly seized overseas territories and began colonizing them.

[17] "Colonial warfare is the only form of encounter in battle remaining where the forces are sufficiently small that the meaning of conflict is comprehensible to the participant.

Due to this emphasis on more direct conflicts, imperial operations and development in colonial ventures often received less attention from the armed forces of nations responsible for them.

French commanders cared little for state policy when conducting their campaigns in Western Sudan in the 1870s and 1880s, while German soldiers in Africa frequently operated contrary to the directions of the colonial bureaucracy.

[1] This included the burning of villages, theft of cattle, and systematic destruction of crops as committed by the French in pacification campaigns in Algeria, and the Germans in the Herero Wars of southern Africa.

[21] Such actions were usually undertaken when there was a lack of political or military goals for an invader to achieve (if there was no central government to seize or organized army to subdue) as a means to subjugate local populations.

[8] Indigenous leaders such as Abdelkader ibn Muhieddine of Algeria, Mahmadu Lamine of Senegal, and Samori Ture of the Wassoulou Empire were able to resist European colonialism for years after disregarding traditional methods and using guerrilla tactics instead.

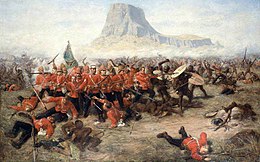

[10] A handful of traditional battles were won by indigenous Asian and African forces with numerical superiority or the element of surprise over colonial powers, but over time they faced staggering losses and discouraging defeats.

From these militias, paid "rangers" were hired to patrol the frontier line and occasionally conduct offensive raids on Native American villages.

[29] With the exception of the raiding expeditions of the French and Indian War, the majority of early colonial campaigns between colonizing powers in North America were fought in order to secure strategic forts.

Still, some managed to form coalitions, such as the alliance between the Sioux, Arapaho, and Cheyenne which dominated the northern region of the Great Plains during the mid-nineteenth century.

In spite of their efforts, the Portuguese conquistadors were only able to establish limited territorial holdings in Sub-Saharan regions, facing tropical disease and organized resistance from Africans armed with iron weapons.

[32] In the 1600s and 1700s, other European powers such as the Dutch, the British, and the French began to take interest in Africa as a means to supply slaves to their American colonies.

[1] While European soldiers were generally more reliable, they were susceptible to diseases in tropical climates that local Africans had adjusted to, making it more optimal (less money had to be spent on medical treatment) for the latter to be deployed in Sub-Saharan environments.

[23] African peoples were relatively disjointed, leading European powers to employ a strategy of divide and rule, aggravate internal tensions, and make use of collaborationism.

Some of this was due to the fact that in many —but not all— places the technological gap between European armies and native forces had shrunk considerably, mostly with the proliferation of quick-firing rifles.

[39] This changed significantly with the widespread adoption of gunpowder between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, giving rise to renewed imperial power in China and Japan.

[40] With the suppression of nomadic steppe raiders (through the use of muskets) and the relatively limited presence of European merchantmen, there was little external pressure to alter their methods of warfare.

Competition between local elites over tax revenue burdened populaces, contributing greatly to the collapse of the Mughal Empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Enhanced power structures solidified the control commanders and political leaders had over their forces, making them effective even when operating far from seats of authority.