Colonisation of Africa

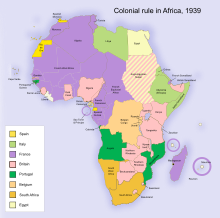

The principal powers involved in the modern colonisation of Africa were Britain, France, Germany, Portugal, Spain, Belgium and Italy.

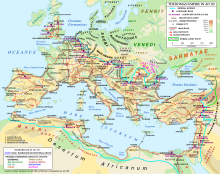

In the early historical period, colonies were founded in North Africa by migrants from Europe and Western Asia, particularly Greeks and Phoenecians.

This became one of the major cities of Hellenistic and Roman times, a trading and cultural centre as well as a military headquarters and communications hub.

The Spanish colonised the Canary Islands off the north African coast in the 15th century, causing the genocide of the native Berber population.

A significant early proponent of colonising inland was King Leopold of Belgium, who oppressed the Congo Basin as his own private domain until 1908.

The 1885 Berlin Conference, initiated by Otto von Bismarck to establish international guidelines and avoiding violent disputes among European Powers, formalized the "New Imperialism", driven by the Second Industrial Revolution.

[13] A decade later the colony seemed conquered, though, "It had been a long-drawn-out struggle and inland administration centres were in reality little more than a series of small military fortresses."

German attempts to seize control in Southwest Africa also produced ardent resistance, which was very forcefully repressed leading to the Herero and Namaqua Genocide.

[14] King Leopold II of Belgium called his vast private colony the Congo Free State.

His barbaric treatment of the Africans sparked a strong international protest and the European powers forced him to relinquish control of the colony to the Belgian Parliament.

Africans also noticed the unequal evidence of gratitude they received for their efforts to support Imperialist countries during the world wars.

While the British sought to follow a process of gradual transfer of power and thus independence, the French policy of assimilation faced some resentment, especially in North Africa.

[24] Farmers in British East Africa were upset by attempts to take their land and to impose agricultural methods against their wishes and experience.

In Tanganyika, Julius Nyerere exerted influence not only among Africans, united by the common Swahili language, but also on some white leaders whose disproportionate voice under a racially weighted constitution was significant.

The theory of colonialism addresses the problems and consequences of the colonisation of a country, and there has been much research conducted exploring these concepts.

He concludes that the structure of present-day Africa and Europe can, through a comparative analysis be traced to the Atlantic slave trade and colonialism.

Achille Mbembe is a Cameroonian historian, political theorist, and philosopher who has written and theorized extensively on life in the colony and postcolony.

He reminds the reader that colonial powers demanded use of African bodies in particularly violent ways for the purpose of labor as well as the shaping of subservient colonised identities.

The reactions of disgust and displeasure to dirt and uncleanliness are often linked social norms and the wider cultural context, shaping the way in which Africa is still thought of today.

The lack of sanitation and proper sewage systems symbolize that Africans are savages and uncivilised, playing a central role in how the west justified the case of the civilising process.

Brown refers to this process of abjectification using discourses of dirt as a physical and material legacy of colonialism that is still very much present in Kampala and other African cities today.

Postcolonial theory has been derived from this anti-colonial/anti-imperial concept and writers such as Mbembe, Mamdani and Brown, and many more, have used it as a narrative for their work on the colonisation of Africa.

Post colonialism can be described as a powerful interdisciplinary mood in the social sciences and humanities that is refocusing attention on the imperial/colonial past, and critically revising understanding of the place of the west in the world.

Both Mbembe, Mamdani and Brown’s theories have a consistent theme of the indigenous Africans having been treated as uncivilised, second class citizens and that in many former colonial cities this has continued into the present day with a switch from race to wealth divide.

On the Postcolony has faced criticism from academics such as Meredith Terreta for focusing too much on specific African nations such as Cameroon.

[31] Echoes of this criticism can also be found when looking at the work of Mamdani with his theories questioned for generalising across an Africa that, in reality, was colonised in very different ways, by fundamentally different European imperial ideologies.