Color photography

By contrast, black-and-white or gray-monochrome photography records only a single channel of luminance (brightness) and uses media capable only of showing shades of gray.

Some early results, typically obtained by projecting a solar spectrum directly onto the sensitive surface, seemed to promise eventual success, but the comparatively dim image formed in a camera required exposures lasting for hours or even days.

Other experimenters, such as Edmond Becquerel, achieved better results but could find no way to prevent the colors from quickly fading when the images were exposed to light for viewing.

[1][2] The method is based on the Young–Helmholtz theory, which states that the human eye sees color using millions of intermingled cone cells of three types on its inner surface.

[4] To emphasize that each type of cell by itself did not actually see color but was simply more or less stimulated, he drew an analogy to black-and-white photography: if three colorless photographs of the same scene were taken through red, green and blue filters, and transparencies ("slides") made from them were projected through the same filters and superimposed on a screen, the result would be an image reproducing not only red, green and blue, but all of the colors in the original scene.

During the lecture, which was about physics and physiology, not photography, Maxwell commented on the inadequacy of the results and the need for a photographic material more sensitive to red and green light.

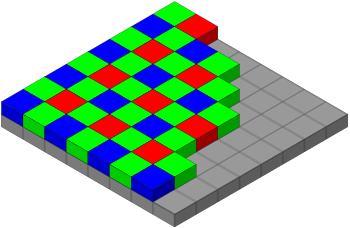

If one of these displays is examined with a sufficiently strong magnifier, it will be seen that each pixel is actually composed of red, green and blue sub-pixels which blend at normal viewing distances, reproducing a wide range of colors as well as white and shades of gray.

Because some of these processes allow very stable and light-fast coloring matter to be used, yielding images which can remain virtually unchanged for centuries, they are still not quite completely extinct.

For making the three color-filtered negatives required, he was able to develop materials and methods which were not as completely blind to red and green light as those used by Thomas Sutton in 1861, but they were still very insensitive to those colors.

[12] Although it would be many more years before these sensitizers (and better ones developed later) found much use beyond scientific applications such as spectrography, they were quickly and eagerly adopted by Louis Ducos du Hauron, Charles Cros and other color photography pioneers.

Later known as "one-shot" cameras, refined versions continued to be used as late as the 1950s for special purposes such as commercial photography for publication, in which a set of color separations was ultimately required in order to prepare printing plates.

It was probably this Miethe-Bermpohl camera which was used by Miethe's pupil Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii to make his now-celebrated color photographic surveys of Russia before the 1917 revolution.

One sophisticated variant, patented by Frederic Eugene Ives in 1897, was driven by clockwork and could be adjusted to automatically make each of the exposures for a different length of time according to the particular color sensitivities of the emulsion being used.

[15] This was a straightforward additive system and its essential elements had been described by James Clerk Maxwell, Louis Ducos du Hauron and Charles Cros much earlier, but Ives invested years of work and ingenuity in refining the methods and materials to optimize color quality, in overcoming problems inherent in the optical systems involved, and in simplifying the apparatus to bring down the cost of producing it commercially.

The color images, dubbed "Kromograms", were in the form of sets of three black-and-white transparencies on glass, mounted onto special cloth-tape-hinged triple cardboard frames.

A Kromskop triple "lantern" could be used to project the three images, mounted in a special metal or wooden frame for this purpose, through filters as Maxwell had done in 1861.

The holder contained the heart of the system: a clear glass plate on which very fine lines of three colors had been ruled in a regular repeating pattern, completely covering its surface.

This was the invention of Irish scientist John Joly, although he, like so many other inventors, eventually discovered that his basic concept had been anticipated in Louis Ducos du Hauron's long-since-expired 1868 patent.

The glass used for photographic plates at the time was not perfectly flat, and lack of uniform good contact between the screen and the image gave rise to areas of degraded color.

Gabriel Jonas Lippmann won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1908 for the creation of the first color photographic process using a single emulsion.

The most recent use of the additive screen process for non-digital photography was in Polachrome, an "instant" 35mm slide film introduced in 1983 and discontinued about twenty years later.

If the three layers of emulsion in a tripack did not have to be taken apart in order to produce the cyan, magenta and yellow dye images from them, they could be coated directly on top of each other, eliminating the most serious problems.

In 1935, American Eastman Kodak introduced the first modern "integral tripack" color film and called it Kodachrome, a name recycled from an earlier and completely different two-color process.

In 1938, sheet film in various sizes for professional photographers was introduced, some changes were made to cure early problems with unstable colors, and a somewhat simplified processing method was instituted.

The expense of color film as compared to black-and-white and the difficulty of using it with indoor lighting combined to delay its widespread adoption by amateurs.

By 1970, prices were dropping, film sensitivity had improved, electronic flash units were replacing flashbulbs, and color had become the norm for snapshot-taking in most families.

Some currently available color films are designed to produce positive transparencies for use in a slide projector or magnifying viewer, although paper prints can also be made from them.

Photographic transparencies can be made from negatives by printing them on special "positive film", but this has always been unusual outside of the motion picture industry and commercial service to do it for still images may no longer be available.

[vague] Though a wide range of film preference still exists among photographers today, color has, with time, gained a much larger following in the field of photography.

After photographic materials are individually enclosed, housing or storage containers provide another protective barrier, such as folders and boxes made from archival paperboard as addressed in ISO Standards 18916:2007 and 18902.