Commodity fetishism

[3] In the process of commercial exchange, commodities appear in a depersonalized form, obscuring the social relations inherent to their production.

[10][11] Marx's first mention of fetishism appeared in 1842, in his response to a newspaper article by Karl Heinrich Hermes, which defended Germany on religious grounds.

But a subsequent sitting would have taught them that the worship of animals is connected with this fetishism, and they would have thrown the hares into the sea in order to save the human beings.In the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, Marx spoke of the European fetish of precious-metal money: The nations which are still dazzled by the sensuous glitter of precious metals, and are, therefore, still fetish-worshippers of metal money, are not yet fully developed money-nations.

[18] In the Outlines of the Critique of Political Economy (Grundrisse, 1859), he criticized the liberal arguments of the French economist Frédéric Bastiat; and about fetishes and fetishism Marx said: In real history, wage labour arises out of the dissolution of slavery and serfdom—or of the decay of communal property, as with Oriental and Slavonic peoples—and, in its adequate, epoch-making form, the form which takes possession of the entire social being of labour, out of the decline and fall of the guild economy, of the system of Estates, of labour and income in kind, of industry carried on as rural subsidiary occupation, of small-scale feudal agriculture, etc.

[19] In A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859), Marx referred to A Discourse on the Rise, Progress, Peculiar Objects, and Importance of Political Economy (1825), by John Ramsay McCulloch, who said that "In its natural state, matter ... is always destitute of value", with which Marx concurred, saying that "this shows how high even a McCulloch stands above the fetishism of German 'thinkers' who assert that 'material', and half a dozen similar irrelevancies are elements of value".

Hence, Smith proposed that a market economy was a self-regulating entity that "naturally" tended towards economic equilibrium, wherein the relative prices (the value) of a commodity ensured that the buyers and sellers obtained what they wanted for and from their goods and services.

[22] In the 19th century, Karl Marx contradicted the artifice of Adam Smith's "naturalisation of the market's behaviour" as a politico-ideologic apology—by and for the capitalists—which allowed human economic choices and decisions to be misrepresented as fixed "facts of life", rather than as the human actions that resulted from the will of the producers, the buyers, and the sellers of the commodities traded at market.

In a capitalist economy, a character mask (Charaktermaske) is the functional role with which a person relates and is related to in a society composed of stratified social classes, especially in relationships and market-exchange transactions; thus, in the course of buying and selling, the commodities (goods and services) usually appear other than they are, because they are masked (obscured) by the role-playing of the buyer and the seller.

Moreover, because the capitalist economy of a class society is an intrinsically contradictory system, the masking of the true socio-economic character of the transaction is an integral feature of its function and operation as market exchange.

Marx thus established that in a capitalist society the creation of wealth is based upon "the paid and unpaid portions of labour [that] are inseparably mixed up with each other, and the nature of the whole transaction is completely masked by the intervention of a contract, and the pay received at the end of the week"; and that:[23][24][25] Vulgar economics actually does nothing more than to interpret, to systematize and turn into apologetics—in a doctrinaire way—the ideas of the agents who are trapped within bourgeois relations of production.

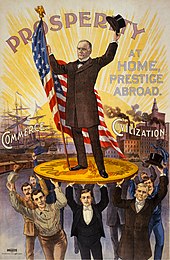

That the religion of capitalism is manifest in four tenets: Since the 19th century, when Karl Marx presented the theory of commodity fetishism, in Section 4, "The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret thereof", of the first chapter of Capital: Critique of Political Economy (1867), the constituent concepts of the theory, and their sociologic and economic explanations, have proved intellectually fertile propositions that permit the application of the theory (interpretation, development, adaptation) to the study, examination, and analysis of other cultural aspects of the political economy of capitalism, such as: In the 19th century, Thorstein Veblen (The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions, 1899) developed the social status (prestige) relationship between the producer of consumer goods and the aspirations to prestige of the consumer.

About which Lukács said: "Just as the capitalist system continuously produces and reproduces itself economically on higher levels, the structure of reification progressively sinks more deeply, more fatefully, and more definitively into the consciousness of Man"—hence, commodification pervaded every conscious human activity, as the growth of capitalism commodified every sphere of human activity into a product that can be bought and sold in the market.

Commodity fetishism is theoretically central to the Frankfurt School philosophy, especially in the work of the sociologist Theodor W. Adorno, which describes how the forms of commerce invade the human psyche; how commerce casts a person into a role not of his or her making; and how commercial forces affect the development of the psyche.

In the book Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944), Adorno and Max Horkheimer presented the Theory of the Culture Industry to describe how the human imagination (artistic, spiritual, intellectual activity) becomes commodified when subordinated to the "natural commercial laws" of the market.

To the consumer, the cultural goods and services sold in the market appear to offer the promise of a richly developed and creative individuality, yet the inherent commodification severely restricts and stunts the human psyche, so that the man and the woman consumer has little "time for myself", because of the continual personification of cultural roles over which he and she exercise little control.

In Capital, Volume 1, Marx remarked that "In bourgeois society the legal fiction prevails that each person, as a buyer, has an encyclopedic knowledge of commodities".

With the concept of commodity narcissism, the psychologists Stephen Dunne and Robert Cluley proposed that consumers who claim to be ethically concerned about the manufacturing origin of commodities, nonetheless behaved as if ignorant of the exploitative labour conditions under which the workers produced the goods and services, bought by the "concerned consumer"; that, within the culture of consumerism, narcissistic men and women have established shopping (economic consumption) as a socially acceptable way to express aggression.

According to James G. Carrier,[34] on a personal level their purchases can make them feel more positively moral and second they can help put pressure on firms in a competitive market to change the way they do things.

Capitalists have the intention of selling to an audience with commercial gain - the use of nature as a strategy is vital in urging people to buy their product.

Ethical consumption is mostly concerned with the social, political and environmental context of objects - and consumers want a product that meets their moral criteria, something non-exploitative.

These capitalists make no point to vary in their images and photographs or captions - the repetition of nature is always colorful and vibrant, gentle and reserved.

Carrier describes how the environment itself is fetishized as a consumable product through parks and other areas of land being used as bodies or images attached to promises of natural experiences or protection efforts in return for money.

What Karl Marx critically anticipated in the 19th century, with "The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret thereof", Guy Debord interpreted and developed for the 20th century—that in modern society, the psychologic intimacies of intersubjectivity and personal self-relation are commodified into discrete "experiences" that can be bought and sold.

The Society of the Spectacle is the ultimate form of social alienation that occurs when a person views his or her being (self) as a commodity that can be bought and sold, because they regard every human relation as a (potential) business transaction.

The economist Michael Perelman critically examined the belief systems from which arose intellectual property rights, the field of law that commodified knowledge and information.

[39] The sociologists Frank Furedi and Ulrich Beck studied the development of commodified types of knowledge in the business culture of "risk prevention" in the management of money.

In the field of law, the scholar Evgeny Pashukanis (The General Theory of Law and Marxism, 1924), the Austrian politician Karl Renner, the German political scientist Franz Leopold Neumann, the British socialist writer China Miéville, the labour-law attorney Marc Linder, and the American legal philosopher Duncan Kennedy (The Role of Law in Economic Theory: Essays on the Fetishism of Commodities, 1985) have respectively explored the applications of commodity fetishism in their contemporary legal systems, and reported that the reification of legal forms misrepresents social relations.