Common Berthing Mechanism

The resulting tunnel can be used as a loading bay, admitting large payloads from visiting cargo spacecraft that would not fit through a typical personnel passageway.

[17] The Type II was used to launch small elements in the shuttle payload bay while bolted to an ACBM or to similar flight-support equipment because the V835 material is more resistant to the damaging effects of scrubbing under vibration.

Type I ACBMs, usually found on axial ports, typically have a "shower cap" cover that takes two EVA crew members about 45 minutes to remove and stow.

Preparation of the ACBM for berthing takes about an hour, beginning with selection of supporting utilities (power, data) and sequential activation for each Controller Panel Assembly (CPA).

[25] Contingencies considered during preparation include cleaning the face of the ACBM ring, and EVA corrective actions involving the M/D Covers as well as the CPA, Capture Latch, and Ready-to-Latch Indicators.

Early berths were guided using a photogrammetric feedback technique called the Space Vision System (SVS), that was quickly determined unsuitable for general use.

Five stages of capture are executed when using the SSRMS in order to limit the potential for loads building up in its arm booms if off-nominal braking events occur.

[31][32] If pre-mission Thermal Analysis indicates that the temperature differential between the two CBM halves is excessive, the ABOLT condition is held for an extended period of time.

The contingency procedures in this phase of operations also address abnormal braking of the SSRMS and "rapid safing" if other systems in the ISS or Shuttle required immediate departure.

The time and effort required depends on the configuration of the ACBM, the number and type of CBM components to be removed, and on the interfaces to be connected between the two elements.

It may be budgeted for as much as ten hours although, in at least some cases, that time might be paused to conduct an extended "fine leak check" by pressure decay before opening the hatch into the vestibule.

It removes items that cross the ACBM/PCBM interface plan (closeouts, utility jumpers, and grounding straps), installs CBM hardware essential to demate operations (e.g., CPA, thermal covers), and closes the hatch.

[39] Pressure decay testing equipment, including sensors and supporting electronics and a Vacuum Access Jumper 35 ft (11 m) in length, are subsequently installed on the inside of the hatch.

The Bishop NanoRacks Airlock Module (NRAL) takes advantage of the robust interface between the ACBM and PCBM to repeatedly berth and deberth a "bell" hosting similar capability.

The berthing operation was developed to do so: a requirement to gently grasp a nearby spacecraft with near-zero contact velocity was allocated to the Shuttle's planned RMS.

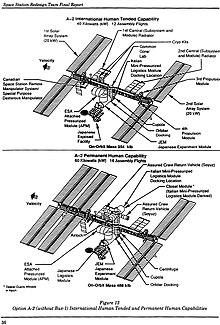

The date of first operation was two months after submission of final reports by the eight contractors of NASA's Space Station Needs, Attributes, and Architectural Options Study.

Even though no flight results were available when the final study reports were written, at least three of them identified "berthing" as the primary means of assembling a Space Station from pressurized modules delivered in the Shuttle's payload bay.

[66] In early 1984, the Space Station Task Force described a Berthing Mechanism that would attenuate the loads incurred when two modules were maneuvered into contact with each other, followed by latching.

Designed for a tensile load of 10,000 lbf (44,500 N), both the bolt and nut were fabricated from A286 steel, coated with a tungsten disulfide dry film lubrication as specified by DOD-L-85645.

Bolt/nut locations alternated in orientation around the perimeter of the 63-inch diameter pressure wall and the faces of both rings included seals, so that the mechanism was effectively androgynous at the assembly level.

[74] Although the dimensions accommodated internal utility connections and a 50-inch square hatchway, the mechanism envelope had limited compatibility with the eventual recessed Radial Port locations on USOS Resource Nodes.

[76] Each bank of equipment was divided into "racks" of standard size that could be installed on orbit in order to repair, upgrade or extend the station's capability.

This approach to integration facilitated a higher level of verification than would have been available using replacement of smaller components, providing for "...easy reconfiguration of the modules over their life span of 30 years."

Until it was cancelled, the Passive Flexible CBM still had an aluminum bellows, but the cable/pulley concept had been replaced by a set of 16 powered struts, driven by the multiplexing motor controller.

The success criteria for these tests were generally based on the torque required to establish and relieve preload, on electrical continuity, and on the accuracy of the bolt's load cell.

For example, the specifications directed capture to be qualified "...by analysis under dynamic loads imposed by the SRMS and SSRMS...validated by assembly-level test that includes variation of performance resulting from temperature and pressure on the ACBM and PCBM and on their interfacing structures.

"[90] Boltup analyses of the ACBM/PCBM interface, and subsequent leakage, required similar validation by element- and assembly-level tests that included the distorting effects of pressure and temperature.

Integrated checkout of the assembled setup in the V20 chamber began with baseline testing of developmental CBM hardware in August 1997, and was completed in November of that year.

See Reference to the ISS (Utilization) (NASA/ISSP, 2015) for berths through April, 2015; additional information is available for the Shuttle flights as noted in the PCBM Element column.

Key to Organizational Authors and Publishers This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.