Drosophila melanogaster

Starting with Charles W. Woodworth's 1901 proposal of the use of this species as a model organism,[7][8] D. melanogaster continues to be widely used for biological research in genetics, physiology, microbial pathogenesis, and life history evolution.

[10][11] Drosophila melanogaster is typically used in research owing to its rapid life cycle, relatively simple genetics with only four pairs of chromosomes, and large number of offspring per generation.

The term "Drosophila", meaning "dew-loving", is a modern scientific Latin adaptation from Greek words δρόσος, drósos, "dew", and φιλία, philía, "lover".

[20] Drosophila melanogaster can be distinguished from related species by the following combination of features: gena ~1/10 diameter of eye at greatest vertical height; wing hyaline and with costal index 2.4; male protarsus with a single row of ~12 setae forming a sex comb; male epandrial posterior lobe small and nearly triangular; female abdominal tergite 6 with dark band running to its ventral margin; female oviscapt small, pale, without dorsodistal depression and with 12-13 peg-like outer ovisensilla.

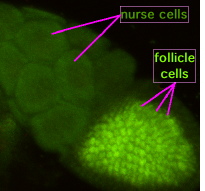

[28][29] Females lay some 400 eggs (embryos), about five at a time, into rotting fruit or other suitable material such as decaying mushrooms and sap fluxes.

[32] Copulation lasts around 15–20 minutes,[33] during which males transfer a few hundred, very long (1.76 mm) sperm cells in seminal fluid to the female.

[36] Gonadotropic hormones in Drosophila maintain homeostasis and govern reproductive output via a cyclic interrelationship, not unlike the mammalian estrous cycle.

[37] Sex peptide perturbs this homeostasis and dramatically shifts the endocrine state of the female by inciting juvenile hormone synthesis in the corpus allatum.

This apparent learned behavior modification seems to be evolutionarily significant, as it allows the males to avoid investing energy into futile sexual encounters.

[46] This modification also appears to have obvious evolutionary advantages, as increased mating efficiency is extremely important in the eyes of natural selection.

[48] While it requires more energy for male flies to court multiple females, the overall reproductive benefits it produces has kept polygamy as the preferred sexual choice.

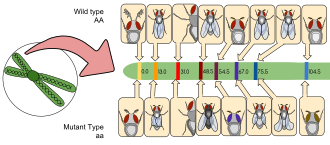

Morgan and his students eventually elucidated many basic principles of heredity, including sex-linked inheritance, epistasis, multiple alleles, and gene mapping.

[51] There are many reasons the fruit fly is a popular choice as a model organism: Genetic markers are commonly used in Drosophila research, for example within balancer chromosomes or P-element inserts, and most phenotypes are easily identifiable either with the naked eye or under a microscope.

To get around this problem, the nuclei that have made a mistake detach from their centrosomes and fall into the centre of the embryo (yolk sac), which will not form part of the fly.

[93][94] Fruit flies reared under a hypoxia treatment experience decreased thorax length, while hyperoxia produces smaller flight muscles, suggesting negative developmental effects of extreme oxygen levels.

[103] While the traits described above are expected to manifest similarly across sexes, developmental temperature can also produce sex-specific effects in D. melanogaster adults.

However, an AAXX cell will produce enough sisterless to inhibit the action of deadpan, allowing the sex-lethal gene to be transcribed to create a female.

The fat body is the primary secretory organ and produces key immune molecules upon infection, such as serine proteases and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs).

AMPs are secreted into the hemolymph and bind infectious bacteria and fungi, killing them by forming pores in their cell walls or inhibiting intracellular processes.

Although the fly's transcriptional response to microbial challenge is highly specific to individual pathogens, Drosophila differentially expresses a core group of 252 genes upon infection with most bacteria.

[124] In 1971, Ron Konopka and Seymour Benzer published "Clock mutants of Drosophila melanogaster", a paper describing the first mutations that affected an animal's behavior.

Since then, Benzer and others have used behavioral screens to isolate genes involved in vision, olfaction, audition, learning/memory, courtship, pain, and other processes, such as longevity.

Following the pioneering work of Alfred Henry Sturtevant[125] and others, Benzer and colleagues[53] used sexual mosaics to develop a novel fate mapping technique.

were isolated by William "Chip" Quinn while in Benzer's lab, and were eventually shown to encode components of an intracellular signaling pathway involving cyclic AMP, protein kinase A, and a transcription factor known as CREB.

The TRP channels nompC, nanchung, and inactive are expressed in sound-sensitive Johnston's organ neurons and participate in the transduction of sound.

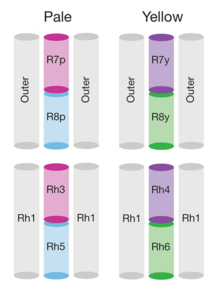

[169] IP3 is thought to bind to IP3 receptors in the subrhabdomeric cisternae, an extension of the endoplasmic reticulum, and cause release of calcium, but this process does not seem to be essential for normal vision.

For example, the eyes and antennae are likely executed early on in the grooming sequence to prevent debris from interfering with the function of D. melanogaster's sensory organs.

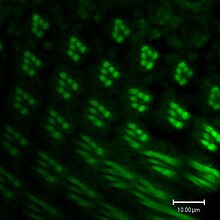

[185] Detailed circuit-level connectomes exist for the lamina[186][187] and a medulla[188] column, both in the visual system of the fruit fly, and the alpha lobe of the mushroom body.

[189] In May 2017 a paper published in bioRxiv presented an electron microscopy image stack of the whole adult female brain at synaptic resolution.

[196] Furthermore, the resolution of electron microscopy illuminates ultrastructural variations between neurons as well as the location of individual synapses, thereby providing a wiring diagram of synaptic connectivity between all neurites within the given dataset.