Complex logarithm

The term refers to one of the following, which are strongly related: There is no continuous complex logarithm function defined on all of

Ways of dealing with this include branches, the associated Riemann surface, and partial inverses of the complex exponential function.

So the points equally spaced along a vertical line, are all mapped to the same number by the exponential function.

One is to restrict the domain of the exponential function to a region that does not contain any two numbers differing by an integer multiple of

Another way to resolve the indeterminacy is to view the logarithm as a function whose domain is not a region in the complex plane, but a Riemann surface that covers the punctured complex plane in an infinite-to-1 way.

On the other hand, the function on the Riemann surface is elegant in that it packages together all branches of the logarithm and does not require an arbitrary choice as part of its definition.

appears without any particular logarithm having been specified, it is generally best to assume that the principal value is intended.

This leads to the following formula for the principal value of the complex logarithm: For example,

is as the inverse of a restriction of the complex exponential function, as in the previous section.

Is there a different way to choose a logarithm of each nonzero complex number so as to make a function

To see why, imagine tracking such a logarithm function along the unit circle, by evaluating

To obtain a continuous logarithm defined on complex numbers, it is hence necessary to restrict the domain to a smaller subset

obtained by removing 0 and all negative real numbers from the complex plane.

The argument above involving the unit circle generalizes to show that no branch of

is typically chosen as the complement of a ray or curve in the complex plane going from 0 (inclusive) to infinity in some direction.

is extended to be defined at a point of the branch cut, it will necessarily be discontinuous there; at best it will be continuous "on one side", like

[2] Another way to prove this is to check the Cauchy–Riemann equations in polar coordinates.

Fortunately, if the integrand is holomorphic, then the value of the integral is unchanged by deforming the path (while holding the endpoints fixed), and in a simply connected region

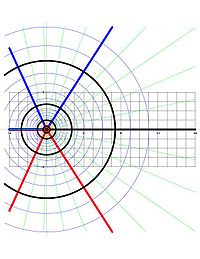

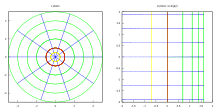

, has the following properties, which are direct consequences of the formula in terms of polar form: Each circle and ray in the z-plane as above meet at a right angle.

Their images under Log are a vertical segment and a horizontal line (respectively) in the w-plane, and these too meet at a right angle.

So it makes sense to glue the domains of these branches only along the copies of the upper half plane.

The resulting glued domain is connected, but it has two copies of the lower half plane.

radians counterclockwise around 0, first crossing the positive real axis (of the

level) into the shared copy of the upper half plane and then crossing the negative real axis (of the

The final result is a connected surface that can be viewed as a spiraling parking garage with infinitely many levels extending both upward and downward.

by gluing compatible holomorphic functions is known as analytic continuation.

This approach, although slightly harder to visualize, is more natural in that it does not require selecting any particular branches.

In fact, it is a Galois covering with deck transformation group isomorphic to

with the only caveat that its value depends on the choice of a branch of log defined at

For example, using the principal value gives If f is a holomorphic function on a connected open subset